If you're looking to buy a new house, you've likely felt the pressure of rising interest rates...

If you're looking to buy a new house, you've likely felt the pressure of rising interest rates...

As the Federal Reserve has increased the benchmark interest rate, the repercussions have trickled down the line. Average rates for 30-year mortgages climbed from 3.37% in February to 5.57% as of a few weeks ago.

Even a two-percentage-point jump can make homes much less affordable...

A customer paying back a standard $500,000 mortgage at 3.37% would pay $295,000 in total interest. It works out to a monthly payment of $2,200. Meanwhile, a homebuyer paying a 5.57% rate would fork over $2,860 per month and pay a total of $530,000 in interest.

In other words... the higher mortgage rate really means you'll pay 80% more interest.

This shift in housing "affordability" is hurting homebuyers. And of course, this situation isn't isolated to the housing industry... From credit cards to corporate debt, higher rates slow spending – and they can stop the flow of financing entirely.

Higher-risk companies don't have a choice but to turn to the high-yield debt market. And even in that space, lending is slowing down. Similar to homebuyers who can't afford houses at 5.57%... higher rates are forcing cash-strapped companies to tighten their belts.

As we often talk about here in Altimetry Daily Authority, corporate credit issuance is one of the key drivers of the economy. It can kick-start spending that flows out and drives employment, home construction, and more.

That's why it's critical to look at the recent slowdown in the high-yield credit market. If the riskiest businesses can't secure financing, who's next? And worse... could it start a panic?

By aggregating the market's debt, we can measure the risk of a panic...

By aggregating the market's debt, we can measure the risk of a panic...

First, let me be clear...

Slowing high-yield debt activity is not the spark that lights the powder keg of a recession. As long as businesses still have cash on hand, an inability to access credit doesn't change anything.

However, problems arise when companies run out of cash and then can't get it. Then, widespread defaults ensue and the entire economy crashes.

To understand where we are today, we need to see what's going on in the credit markets...

Long-term interest rates, driven by the Fed's rate hikes, are currently at the high end of their 2018 levels, when the markets had dipped. However, interest rates aren't yet at Great Recession levels, when the cost to borrow for high-yield companies was higher than 10%. That's why the market froze and mass defaults rocked the economy.

Today, companies are slowing their borrowing habits. They're figuring out if they really need the money. And that's where things get interesting...

Using our Credit Cash Flow Prime ('CCFP') analysis, we can look at aggregate corporate credit risk...

Using our Credit Cash Flow Prime ('CCFP') analysis, we can look at aggregate corporate credit risk...

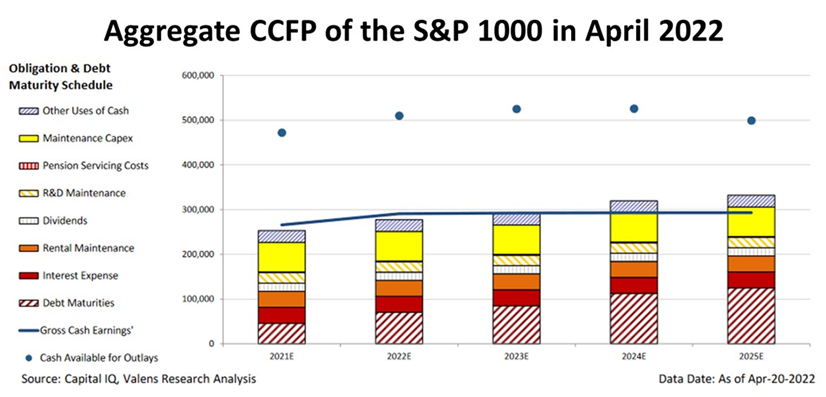

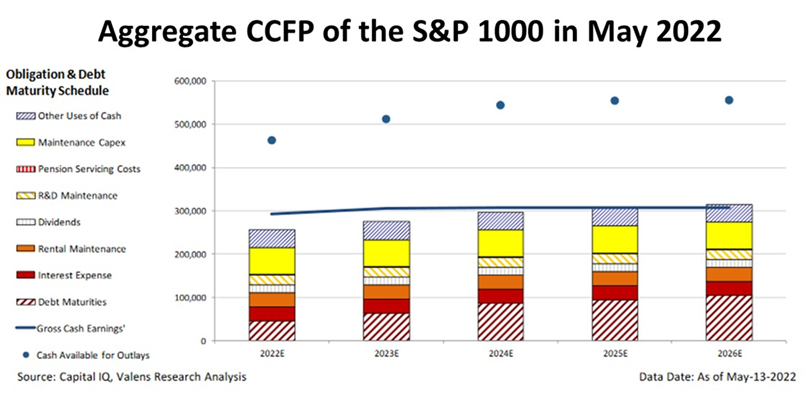

Our CCFP analysis allows us to visualize a company's cash flows versus its annual obligations – debt, capital expenditures, dividends, and more.

From there, we can combine the CCFPs of the entire S&P 1000 Index. That provides us with a good proxy of corporate America's credit health.

In the charts below, the stacked bars represent corporate America's total obligations each year through 2028. Then, we compare these obligations to aggregate cash flows (blue line), as well as the cash on hand at the beginning of each period (blue dots) and available cash and undrawn revolver (blue triangles).

As of this month, all S&P 1000 companies have reported their 2021 earnings. As a result, we have a comprehensive view of their 2021 fiscal data and 2022 forecasts.

And importantly, the picture for the debt environment has actually improved...

Back in April, the aggregate CCFP showed a jump in debt-maturity headwalls in 2024 – to the point where cash flows alone couldn't service all obligations. That's partially why we've often talked about how 2024 or 2025 could be when the economy boils into a crisis.

But over the past month, companies have reported healthier financials.

Now, the S&P 1000's aggregate cash flows cover obligations through 2024. That paints a much better picture of economic health and lowers the risk of a crash...

The reason why we're not seeing debt issuances right now is simple...

No one needs the money.

Instead, they're waiting. And they'll only borrow if growth really makes sense.

Without serious risk of default, it's clear that the market is holding off on further debt issuances for now. And like everyone else, it's watching for where rates go next.

Regards,

Joel Litman

June 6, 2022

If you're looking to buy a new house, you've likely felt the pressure of rising interest rates...

If you're looking to buy a new house, you've likely felt the pressure of rising interest rates...