Whether a stock is a growth or value stock isn't the only characteristic that matters when investing...

Whether a stock is a growth or value stock isn't the only characteristic that matters when investing...

Wealth-management firm William Blair put out a great piece earlier this month on 'lifecycle' investing. The idea is that if you invest across companies early in their lifecycles – such as startups and high-growth but still-profitable companies – you get diversification.

When Joel and I worked at Credit Suisse, the company was similarly doing research on this lifecycle strategy. It's a powerful framework for thinking in a different way about investing.

Instead of just focusing on finding stocks that trade at a discount to intrinsic value, or stocks that can produce earnings growth that will drive the company higher, by diversifying across the lifecycle you can improve the odds that no matter where the market and economy are, you have an investment in the right stage of its lifecycle to benefit.

Understanding where your investments are in their corporate lifecycle also impacts how you think about analyzing the company, and what matters to make its stock move higher.

Early lifecycle companies should be focused on growth first and foremost... and if the business isn't delivering on growth, its stock is likely to struggle. The company we'll examine today is one such example.

More mature companies should be primarily focused on maintaining profitability. A big, steady company like Procter & Gamble (PG) is unlikely to create a new market in personal goods that's going to transform the value of its business.

If it plows billions of dollars into creating one – thus letting returns suffer to chase growth – the market is likely to react negatively. But if the company can find ways to show the market that it's protecting, maintaining, and improving profitability through managing costs and protecting its market share, the market will reward it.

When looking at your investments, consider where the business is in its lifecycle and if it's doing what it should be doing... not just whether it looks intrinsically undervalued or overvalued.

In yesterday's Altimetry Daily Authority, we discussed the economics of digital marketplaces...

In yesterday's Altimetry Daily Authority, we discussed the economics of digital marketplaces...

We highlighted how food-delivery company Grubhub (GRUB) has a fantastic business model, but has been unable to fend off competitors.

The company failed to maintain its competitive advantage at its peak and, as a result, has seen its profitability cut by more than half since 2014.

To put this into context, Grubhub still earns a 50% return on assets ("ROA"). This is because it had low investment hurdles to reach its current size and was able to ramp quickly.

Grubhub's big problem is its inability to stave off copycats – a problem that many digital-marketplace companies fail to address.

However, there's another problem that plagues many similar companies that can be far more damning – and there may be some unexpected businesses succumbing to it...

Yesterday, we mentioned the poster child for online marketplaces, or "platforms" – ride-hailing company Uber (UBER).

It was the largest "unicorn" in the world before it went public in May, and is viewed as one of the most admired mobile marketplaces... spawning many copycat apps like Lyft (LYFT), Via, and Gojek, to name a few.

As we mentioned yesterday, it has become synonymous with the idea of a digital marketplace (think of all those "the Uber of" designations).

Despite the acclaim for the platform business model, Uber has faced serious operational issues that have become more apparent since its initial public offering ("IPO"). These stem from a decision the company made early on in its history...

Rather than employing a similar approach to a company like Grubhub – which built a massively profitable business and has since had to fend off competition – Uber chose the exact opposite route.

It focused solely on attempting to gain market share and squash its competition, and has since been trying to figure out how to make money on the backend.

This isn't an uncommon strategy. To a certain extent, big retailers Walmart (WMT) and Amazon (AMZN) chose to accept razor-thin margins in the short term in order to starve smaller competitors in a war of attrition. Once they eliminated their competition and dominated the market, they were able to pursue more profitable strategies.

The problem for Uber is simple – its competitors are acting the same way, because all of them are backed by deep-pocketed investors.

Uber stormed onto the ride-hailing scene with such force for a few reasons...

First, it was more convenient than a cab. The whole process of ordering an Uber, from pickup to drop-off to payment, happens in a seamless app.

More important was the price. Ubers were cheaper than cabs, Lyfts, and just about anything else.

This was intentional – rather than risk being undercut by competitors, Uber decided to maximize its cut of the total addressable market ("TAM").

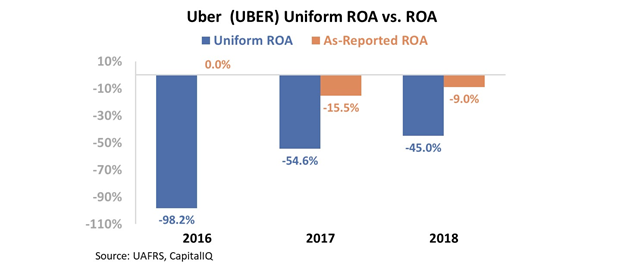

Because of this decision, Uber loses money on every ride taken on its app. The company's Uniform ROA has been below negative 40% in each year since 2016. And while Uniform ROA has not come close to positive levels, as-reported ROA has improved to negative 9%, which may lead investors to think Uber is on trend to become profitable in the near future.

Though it's not unusual for startups to have a negative ROA, Uber's profitability is substantially negative... and it will likely take several more years of market domination to achieve positive profit.

That said, to make matters worse, Uber hasn't dominated the market in the way it hoped to. While the company received significant funding from investors prior to its IPO, main competitors Lyft and Didi Chuxing were also well-funded and chose the same strategy.

While Didi effectively squashed Uber in China, Lyft has pushed Uber to an effective stalemate here in the U.S. At this rate, both Uber and Lyft are trying to starve each other, and neither company is making any money in the process.

This stalemate is unlikely to resolve itself anytime soon. Uber has attempted to steal market share in other ways, like with its Uber Eats food-delivery platform. Unfortunately, as we discussed yesterday, the food marketplace is also crowded with competition.

Despite the challenging road ahead for Uber, investors remain bullish.

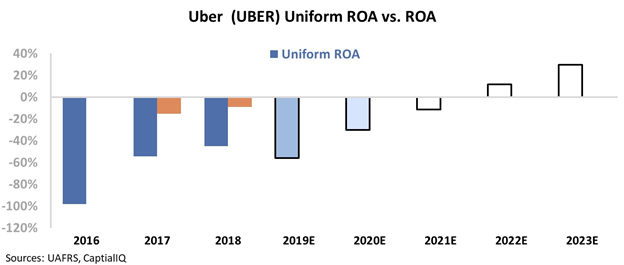

The chart below shows Uber's historical corporate performance levels (dark blue bars) versus what sell-side analysts think the company is going to do over the next two years (light blue bars) and what the market is pricing in at current valuations (white bars).

While analysts expect Uber's Uniform ROA to remain largely negative, the market is pricing in expectations for its ROA to reach 25%-plus levels by 2023. Take a look...

Grubhub has a 50% Uniform ROA right now, so those expectations could be possible for Uber... but Grubhub is also seeing its Uniform ROA trend toward corporate-average levels. We don't think that Uber will do much better than that. Unlike Grubhub, Uber has still never shown that it can even be profitable.

Despite the market's optimism, it appears unlikely that Uber will turn this around any time soon. Contrary to what as-reported financials imply, the company is far away from becoming a positive-return business.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

January 15, 2020

Whether a stock is a growth or value stock isn't the only characteristic that matters when investing...

Whether a stock is a growth or value stock isn't the only characteristic that matters when investing...