Tonight is a must-see opportunity to hear multiple investing greats give their 2020 outlook...

Tonight is a must-see opportunity to hear multiple investing greats give their 2020 outlook...

Our friends at Stansberry Research are hosting a special event tonight at 8 p.m. Eastern time that we highly recommend you attend.

Porter Stansberry, Dr. David Eifrig, and Dr. Steve Sjuggerud will be speaking for likely the only time this year on camera together for a special webinar. They're each going to give their market outlook for 2020... their favorite stock picks for the year... and their opinions on cryptocurrencies, gold, and other hot topics.

Plus, they'll introduce Stansberry's newest guru. He's a guy who we respect... and he has previously worked in the hedge-fund industry – including at some of our institutional clients.

If you care about thoughtful research and how 2020 might shake out for your portfolio, you don't want to miss this event. It's completely free to attend, and you can register for it right here.

It once looked like this company was winning the marketplace battle... until it wasn't.

It once looked like this company was winning the marketplace battle... until it wasn't.

Just a few years ago, the list of tech "unicorns" – private companies with a valuation of more than $1 billion – was comprised of almost completely digital "marketplace" companies. At the top of the list was the triad of ride-hailing businesses: Uber (UBER), Lyft (LYFT), and China-based Didi Chuxing.

A bit further down the list, you'd find the "Uber of lodging," Airbnb... the "Uber of groceries," Instacart... and Grab, which is quite literally the "Uber of Southeast Asia."

The "Uber of..." movement became an easy way for businesses to describe themselves as a mobile marketplace. In fact, the term became so overused that content company Ceros decided to make a satirical city named Uberville.

What we're really talking about when we discuss these Uber clones is simply a digital marketplace. Put another way, these companies are "platforms" for buyers and sellers to interact.

This begs the question – why do marketplace companies command such massive valuations? Can they really be that profitable?

The benefit of a digital marketplace is simple... Buyers and sellers alike have far more options online than they would otherwise. A platform itself doesn't have to hold inventory or have an operating location – it just makes money by taking a small amount from each transaction that occurs on the marketplace.

Take food-delivery, for instance. In the early 2000s, delivery choices were a local pizza joint, a sub shop, or perhaps a Chinese restaurant that mailed out copies of their menus. This limited options for consumers, but it also made it challenging for restaurants to find new customers.

This is why digital food-marketplace apps have become so popular. Companies like Grubhub (GRUB), DoorDash, and Postmates expand the universe of restaurants and customers in exchange for a small fee on every transaction. So let's see how the economics play out...

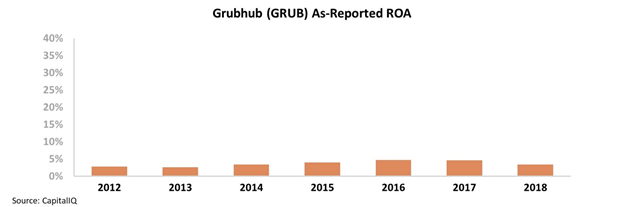

When looking at Grubhub's return on assets ("ROA") on an as-reported basis, its services look more like a charity than a business. Since going public in 2014, the company's ROA has been below long-term corporate averages – never eclipsing 5%...

Many of these startup technology companies are misunderstood due to misleading accounting principles.

However, there's a reason so many of these marketplace businesses end up as unicorns. When one of these companies builds a large enough platform to attract most of the buyers and sellers, the potential returns are massive. This is because it costs very little additional investment for firms like Grubhub to host 10,000 restaurants versus 100,000.

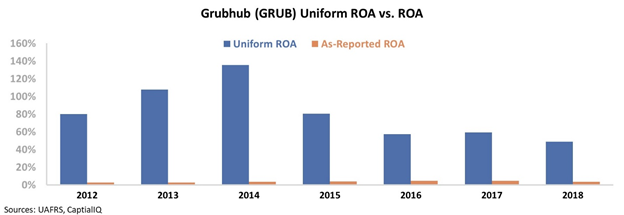

Let's apply our Uniform Accounting framework to Grubhub. We adjust for issues many startups face – like the treatment of non-cash stock option expense (a way to give employees a stake in the company), goodwill, and research and development (R&D) expensing versus capitalization. Using Uniform Accounting, it's possible to see the real economics of digital marketplaces.

Rather than having subpar returns, Grubhub has actually maintained at or above 50% levels since its inception. Take a look...

This helps explain why just about every startup is trying to replicate this business model.

However, that may have actually hurt the cause...

Around the time Grubhub went public, it had a strong position in the online food marketplace. That's especially apparent when looking at its Uniform ROA, which peaked at around 140% in 2014.

But since then, Grubhub has faced the same issue that many of the platform unicorns have seen... Copycats flood the market, pricing at low rates to try to capture the markets and get almost monopolistic positioning. But the reality is that most of these businesses have low barriers to entry.

Several competitors – including DoorDash, Caviar, and even Uber Eats – have grown their reach to match that of Grubhub's.

Because Grubhub was never able to fully capture the market, competition has caused the company's ROA to fall from around 140% at its peak to levels near 50%.

Unfortunately, investors already see the writing on the wall as more competitors enter the space.

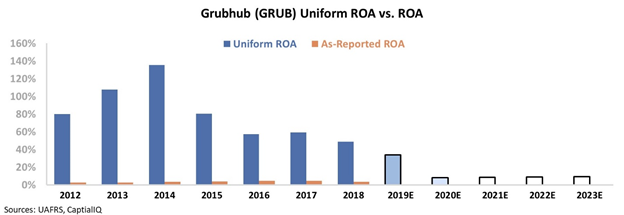

The chart below shows Grubhub's historical corporate performance levels (dark blue bars) versus what sell-side analysts think the company is going to do over the next two years (light blue bars) and what the market is pricing in at current valuations (white bars).

As you can see, both analysts and the market expect ROA to continue declining towards corporate-average levels...

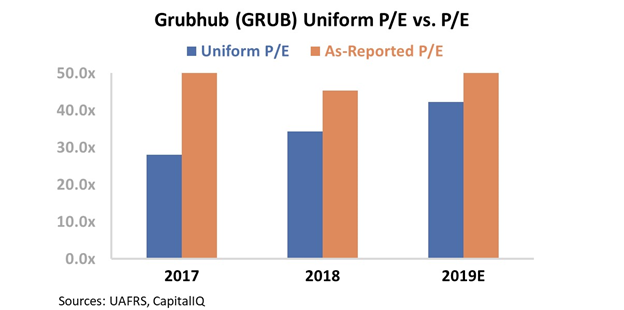

And yet, even with such bearish market expectations, Grubhub's valuations are still expensive. The company's price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio sits at 42, implying investors still think the business is going to grow massively.

At these valuation levels and current investor expectations, the market is bound to be disappointed if competition continues to increase.

While Uniform metrics highlight that digital marketplaces can be economically viable, they also show why so many competitors have begun to enter the market. Stay tuned... Tomorrow, we'll discuss Uber and see what Uniform Accounting says about the platform that accelerated the business model fad.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

January 14, 2020

Tonight is a must-see opportunity to hear multiple investing greats give their 2020 outlook...

Tonight is a must-see opportunity to hear multiple investing greats give their 2020 outlook...