A week ago, we received a great question in one of our classes...

A week ago, we received a great question in one of our classes...

We were teaching a remote class at Hult International Business School the weekend before the Independence Day holiday. One of the students asked a question that I thought particularly relevant for the current market context, with big swings happening almost every day.

He asked how to think about those massive moves, and if it meant that everyone was buying and selling... or that the government was involved... or what? The student just couldn't comprehend how such staggering moves could happen without some coordination.

Rob and I both took some time to answer the question and give a bit more explanation based on his follow-up.

As we said, it really comes down to supply and demand...

The market doesn't move up and down because everyone is buying and selling at once. It moves for exactly the opposite reason – most people aren't buying or selling in a given day.

At Valens Research – the firm that powers Altimetry – one of our big institutional clients has been known to make up more than 20% of the daily average value traded on the New York Stock Exchange on a given day. That's a mind-blowingly massive amount of trading. It also highlights that for that one client to make up that much volume on a single day, most people are likely not trading at a given time.

The reason you can see big swings in the market is because of that "voting mechanism" we discussed yesterday. The market price isn't one price that everyone is agreeing on... Rather, the market trades at a certain price because a bunch of people have a range of opinions on what the market is really worth.

Where optimism and pessimism are equally weighted... that's the market price for a company, or for the market as a whole.

When new information comes out, everyone needs to take that account in their models. That may cause some investors to move where they sit on their outlook for the market. As those investors change their expectations and buy and sell, if there aren't enough buyers, the market drops until there are enough buyers that the market comes in equilibrium again.

As said yesterday, at current valuations, the market equilibrium is pricing in particularly positive signals.

Putting the market in the context of a lot of competing outlooks – both positive and negative – can help give context to why the market can "disagree with you" for so long.

It's not that the entire market is disagreeing with your take on a company, or the market as a whole. It's that just enough people are disagreeing to prevent the market from rising – or falling – as you expect.

1983 was a difficult year for the video-game market...

1983 was a difficult year for the video-game market...

Personal computers were quickly catching up in popularity and functionality to the video-game console market, and the video-game makers saturated the market.

These gaming companies were scrambling to push out content in the hope of capturing demand, sometimes with exceptionally low quality.

Atari even made what's sometimes considered the worst video game of all time based on E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

The game sold so poorly that the company had to bury most of the copies in a landfill. Not only was the game poorly designed, but apparently Atari made more copies of the game than there were consoles at the time.

With rising competition and declining quality, the video-game market collapsed between 1983 and 1985, with revenues contracting by 97%.

Atari would never fully recover. It became a glaring warning for its successors.

Eventually, companies like Nintendo (NTDOY) learned from Atari's mistakes. When Nintendo launched a new gaming system in 1986, it sought to have more control on content and to be more thoughtful about its releases.

Nintendo's goal was to change the video-gaming industry model. No longer would it be a commodity business with companies rushing out content to catch the extra dollar, lowering overall quality.

Instead, by managing supply of content titles and content itself, Nintendo could elevate the platform, turning it into a higher-return business. Nintendo would benefit... as would the game suppliers that could bring quality content.

Nintendo isn't the only business that has tried to justify itself as a high-return business in a commodity market. One other example is Schlumberger (SLB), one of the largest oilfield-services companies in the world.

Rather than drilling oil itself, Schlumberger supplies other companies with the technology, tools, and support for them to successfully maintain their oil operations.

For years, oilfield-services suppliers like Schlumberger have justified their position in the industry by investing in value-added services like site testing and advanced drill technologies.

However, just like how video-game makers are exposed to the video-game console market, oilfield-services firms are exposed to the oil market. And not even OPEC has had success in changing the dynamics of the oil industry like how Nintendo tried to change the gaming industry.

Schlumberger's massive value-add investments were short-lived once the oil market started struggling.

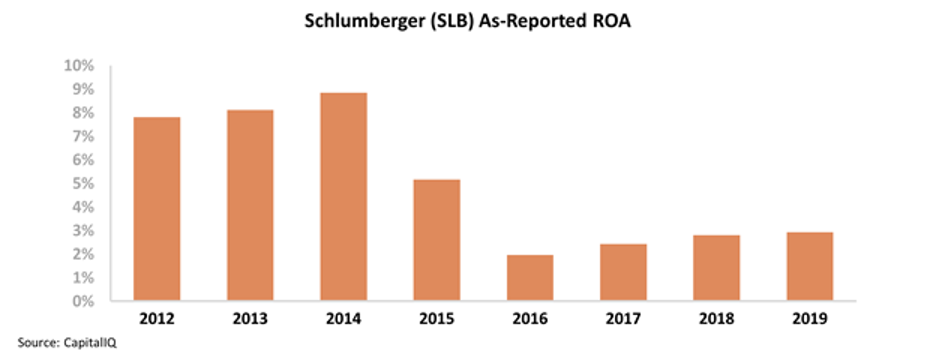

Looking at Schlumberger's as-reported financial metrics, it's clear that suppliers are just as exposed to the end market as the drillers.

From 2014 to 2016, the company's return on assets ("ROA") plummeted from 9% to just 2% as oil prices came under pressure. Take a look...

Since then, Schlumberger's returns look like they've remained muted – only improving back to 3%, but still well below long-term corporate averages near 6%.

Despite the fact that oil started rebounding again from 2017 until early 2020, Schlumberger's as-reported returns remained low.

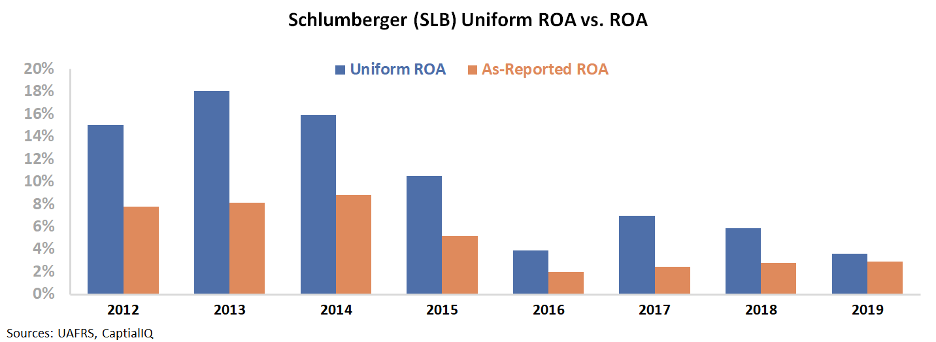

But its Uniform returns look slightly different.

Once we apply our Uniform Accounting metrics – which adjust for inconsistencies like the treatment of goodwill, operating leases, and special items – it's clear that Schlumberger's returns have been closely tied to fluctuations in the oil market since 2016.

Since 2016, Schlumberger was able to once again differentiate itself as a great oilfield-services provider... and its Uniform ROA reflected this.

After bottoming out at 4% in 2016, the company's Uniform ROA expanded back to a peak of 7% in 2017. It was only a matter of time before oil once again came under pressure, though.

Unfortunately for Schlumberger, oil prices have been shaky for the past year – especially during the coronavirus pandemic.

Given the commodity nature of its end market, it was only a matter of time before Schlumberger's returns collapsed again – there's no way to bury excess oil in a landfill like you can with video-games.

The as-reported metrics seem to understate just how sensitive Schlumberger's returns are to the oil market. Even this high-tech business is dependent on its end market, and its returns can't sustain high levels if that market is under pressure.

Regards,

Joel Litman

July 7, 2020

A week ago, we received a great question in one of our classes...

A week ago, we received a great question in one of our classes...