There's a reason we rarely write about oil and gas companies here at Altimetry...

There's a reason we rarely write about oil and gas companies here at Altimetry...

They're generally poorly performing businesses that operate in a cyclical industry. These companies are also tied closely to the volatile price of oil.

Energy stocks have underperformed the market for nearly a decade... and the energy sector is now the smallest component of the S&P 500 Index for the first time in history. Despite this, investors continued to pour money into these companies until 2015.

As recently as 2012, ExxonMobil (XOM) was the largest company in the U.S. by market cap. But this year, it recently lost its spot in the top 30 companies of the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

The energy companies that were part of investor mania in the early 2010s were often negative-cash-flow giants, raising massive equity issuances with the promise of expanding shale drilling to drive growth. However, energy companies never had any vision on how to turn this massive spending into actual profitability.

And when investors stopped happily throwing good money after bad in the industry, many of the companies – such as SandRidge Energy (SD), Samson Resources, Sabine Oil & Gas, Ultra Petroleum, and Energy XXI – ended up declaring bankruptcy. They couldn't possibly generate the cash flow to justify the debts they'd taken on.

Last week at Altimetry, the irony was palpable when an interesting Bloomberg Opinion piece declared that electric-car company Tesla (TSLA) was following the same path. At first glance, Tesla and these struggling oil giants appear to be complete opposites, since much of what Tesla does is focused on eliminating the need for oil and gas.

However, as is often the case, these opposites are mirror images. Tesla and the oil companies are negative-cash-flow businesses with insatiable demand for outside capital. After seeing a huge stock run-up, Tesla capitalized by selling $5 billion in additional stock this month. The company is feverishly looking to raise capital while the going is good... much like the oil and gas firms in 2016.

That said, outside of recent quarters, which have been inflated due to the sale of regulatory credits, Tesla seems to be stumbling on the path to profitability. Much like the oil and gas companies of the past decade, the promise of a revolutionary story has enabled capital raises despite weak markets... and negative profitability.

Investors who don't proceed with caution are likely to be disappointed.

And yet, many investors aren't proceeding with caution... as Tesla's stock has been on a historic run.

And yet, many investors aren't proceeding with caution... as Tesla's stock has been on a historic run.

Since the start of 2020, TSLA shares have risen from a split-adjusted $89 to a recent intraday peak of around $500 – a gain of more than 450%. This has led the company's market cap to hit more than $400 billion earlier this month, making it the most valuable automotive company in the world. Tesla is currently ranked among the 10 largest companies in the U.S., passing historic giants such as Disney (DIS), Walmart (WMT), and Coca-Cola (KO).

In July, Tesla rocketed past Toyota Motor (TM) to take the top automotive title – thus marking a changing of the guard in the industry. This comes as Tesla delivered slightly less than 367,000 vehicles in 2019... well below the level of Toyota, which has reached more than 10 million per year.

Tesla investors have rallied behind eccentric CEO Elon Musk, whose tweets can shave or add billions of market value in minutes. Earlier this week, we saw this yet again when Musk tweeted about the company's battery event.

In contrast, Toyota has taken a much more traditional route: steadily increasing its offerings and value over the decades.

Toyota has recently focused its efforts on developing an electric-vehicle ("EV") fleet to counter the growing competition of Tesla. Despite having no all-electric vehicles currently on the road, Toyota has expressed plans to earn half of all its sales from EVs in 2025. These lofty ambitions are fueled by recent deals with Panasonic to produce batteries for its EVs.

Recently, Altimetry Daily Authority reader John asked us to examine Toyota from a Uniform Accounting perspective. Understanding Toyota's true performance can give some insight into whether there has been an actual changing of the guard... or if the Tesla growth story has been built on mostly hype.

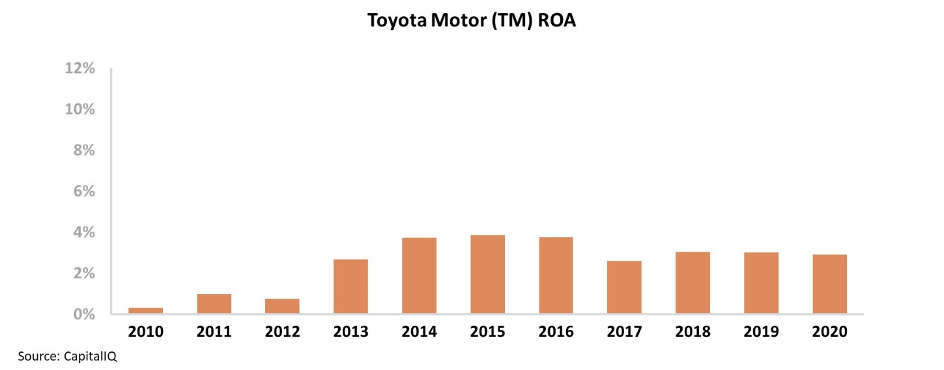

On an as-reported basis, Toyota has been a relatively stable company after recovering from the Great Recession. Its as-reported return on assets ("ROA") has sat between 3% and 4% from 2013 to 2020.

GAAP metrics appear to confirm Toyota's market position: a diversified but low-return auto manufacturer. As evidenced by its stable returns, the company appears to be a consistent operator, selling a great number of low-margin vehicles year after year.

This could indicate that a changing of the guard may have indeed happened, since Toyota just hasn't seen similar improvement. However, it could also mean that this slow-and-steady operator hasn't been fully affected by increased competition... and can wait for the Tesla rabbits to run themselves tired.

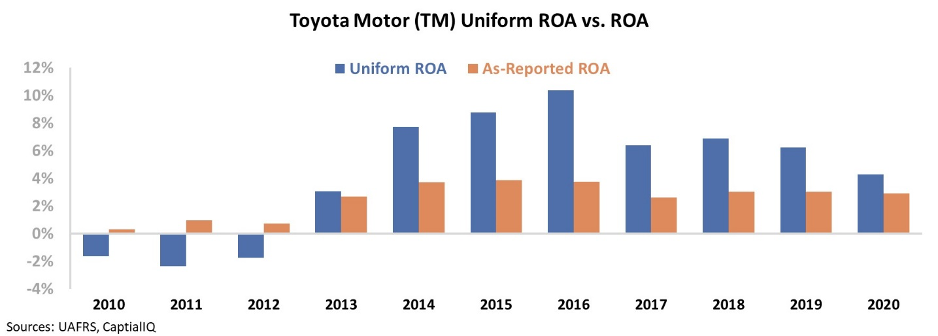

And yet, this picture of Toyota's performance is inaccurate – the company's real performance is masked by distortions in as-reported accounting. Due to the GAAP treatment of financial subsidiaries – among other distortions – Wall Street isn't seeing the real story.

The reality is that Toyota has faced much more operational pressure than as-reported metrics indicate. Although its Uniform ROA grew impressively from 2012 to 2016, the company's returns have seen steady declines since then. Uniform ROA peaked at 10% in 2016, before falling to 4% by 2020.

Toyota has clearly seen larger competitive pressures from other car companies – including electric alternatives such as Tesla – thus pressuring its returns.

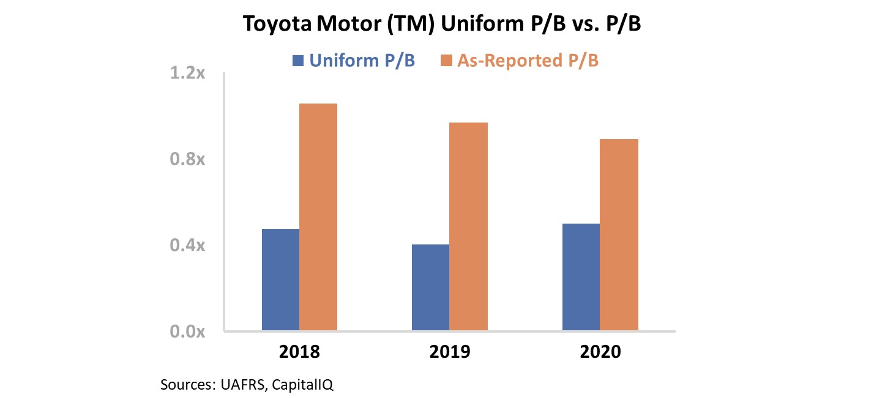

If Toyota continues to suffer from competition, current pessimistic valuations of a Uniform price-to-book (P/B) ratio of 0.4 may be warranted...

In Toyota's case, we look at a P/B valuation rather than a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, as the company doesn't make back its cost of capital. That means a P/E ratio starts to become distorted as Toyota is valued more on its asset base.

Right now, the market is pricing in the possibility that Toyota's returns may never recover to above cost-of-capital levels. The company can't battle back from the competition that has hurt its returns.

Essentially, the market is betting that Tesla and other automotive upstarts will win. On the other hand, if Toyota can effectively enter the EV space, take market share, and see returns recover, its P/B ratio could move toward 1... which would point to significant upside potential.

Overall, Uniform Accounting shows the true trajectory of Toyota's business over the past few years. Without looking at the real numbers, investors would have thought Toyota was a mature company maintaining its returns, not a firm at the crossroads of profitability that may be passing the torch.

Regards,

Joel Litman

September 24, 2020

There's a reason we rarely write about oil and gas companies here at Altimetry...

There's a reason we rarely write about oil and gas companies here at Altimetry...