A sleepy corner of the Internet comes into full focus thanks to private equity and Uniform Accounting...

A sleepy corner of the Internet comes into full focus thanks to private equity and Uniform Accounting...

Domain registries are a core part of the "piping" of the Internet, but people rarely pay much attention to them. However, one of the forgotten parts of this quiet area of the Internet has recently come into focus: the .org domain world.

The Public Interest Registry is a not-for-profit that runs the .org domain registry. Its focus historically has been to guarantee .org domains be inexpensive for not-for-profit entities to register.

The .org franchise was owned by Verisign (VRSN) in the early 2000s, along with .com and .net – arguably the two most profitable domains at the time. To keep the other two domains, Verisign basically donated .org back to ICANN, the organization that regulates Internet domains.

ICANN then chose the nonprofit Internet Society to take control of .org, and the Society created the Public Interest Registry to do just that. When ICANN granted the registry rights, it even capped the price that could be charged for a .org domain.

But in early 2019, ICANN agreed to remove the cap on prices for .org sites. Suddenly, one of the most popular domain suffixes on the Internet by number of sites had a very different economic profile.

Unsurprisingly, in short order, private equity started circling. In this case, a firm called Ethos Capital – which is affiliated with the former CEO of ICANN – made an offer for the Public Internet Registry and the .org domain registry rights for more than $1.1 billion.

The deal drew significant resistance from those who feel the Internet should have the lowest possible barriers to entry... including one of the creators of the Internet, Tim Berners-Lee. Subsequently, just last week, ICANN voted to kill the deal – highlighting the importance of the .org domain remaining in not-for-profit hands.

But it's worth asking... Why would a private-equity firm be interested in this space, considering how boring and staid it is? It can't be that the space would be that profitable, even after caps were removed on domain registration costs, right?

The reality, as GoDaddy shows (GDDY), is actually the opposite...

The company is one of the largest domain registrants in the world, offering everything from basic domain registration to website design and other services.

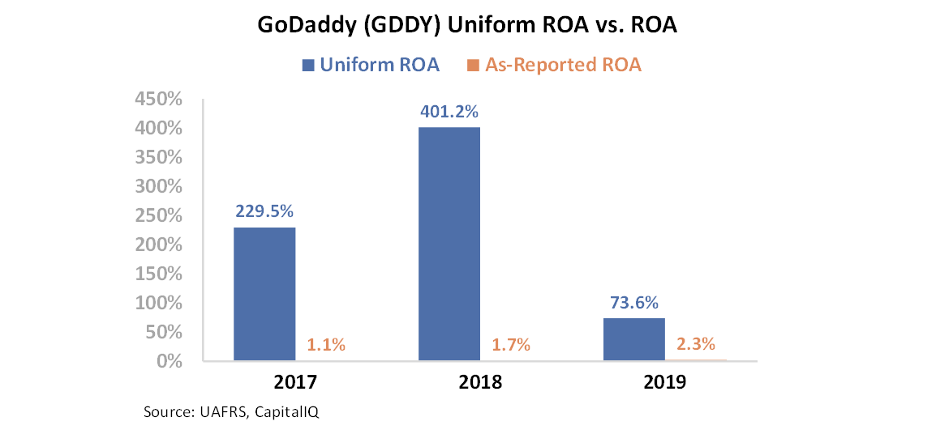

As-reported metrics make it look like this is truly a sleepy business, with an as-reported return on assets ("ROA") that has been below 3% over the past three years.

But after we make our Uniform adjustments, we can see that GoDaddy has generated massive returns since 2017. Sure, returns cratered in 2019... to 73%.

GoDaddy shows just how profitable this boring business can be.

And that's why Ethos Capital was so interested in getting control of the .org domain registry... and it's why many people were concerned about how it could disrupt the economics of this corner of the Internet.

Coming off Berkshire Hathaway's (BRK-B) annual meeting last Saturday, it's worth looking at CEO Warren Buffett's business model...

Coming off Berkshire Hathaway's (BRK-B) annual meeting last Saturday, it's worth looking at CEO Warren Buffett's business model...

Berkshire has one of the most defensible business strategies of all time.

All the company does is buy great, high-quality businesses with strong economic moats and solid management teams at reasonable prices.

After that, Buffett and Vice Chairman Charlie Munger let the portfolio companies do what they do best. It sounds easy enough... but it has led to nearly unparalleled returns for Berkshire.

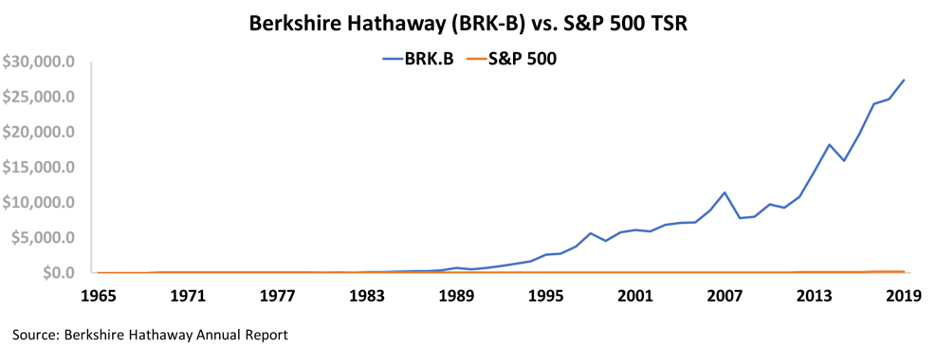

The company has published its annual returns versus the benchmark S&P 500 since 1965, and the results are somewhat staggering. Take a look at the total shareholder return ("TSR") comparison...

Berkshire's massive rise over the past 55 years makes the S&P look like a flat line. In reality, the S&P was up nearly 200 times in that period, whereas Buffett managed to lead Berkshire's market value to be more than a 27,000-bagger.

It's been an incredible run, but unfortunately it doesn't seem like it can last forever. Buffett is now 89 years old, and Munger is 96.

Even though Buffett and Munger have been succession planning for years, part of the value of Berkshire still lies with the old guard.

Not only that, but investors are unsure whether the transition can be executed smoothly.

Berkshire is currently sitting on $64 billion in cash, and it's yet to be seen whether Buffett and Munger's successors will be able to put that to good use.

A big part of Berkshire's strategy over the years was its ability to buy relatively small companies and empower them to grow rapidly – it did just that with household names like Dairy Queen, See's Candies, and Fruit of the Loom.

These days, the company struggles to find investments that can truly "move the needle" because of how big the firm has grown.

But what if Berkshire's strategy could be reproduced by a smaller firm? This would mean it was easier for the company to find acquisition targets, and reproduce the epic returns that Berkshire has historically had.

Every investor is looking to buy into Berkshire at the ground floor. And today, that may be possible with Roper Technologies (ROP)...

Similar to Berkshire, Roper is a conglomerate that operates by buying smaller portfolio companies and letting them grow.

While most of its acquisitions aren't small by today's standards, they're significantly smaller than Berkshire's – with most acquisitions closing for less than $4 billion.

Similarly, Roper looks for undervalued firms with strong economic moats.

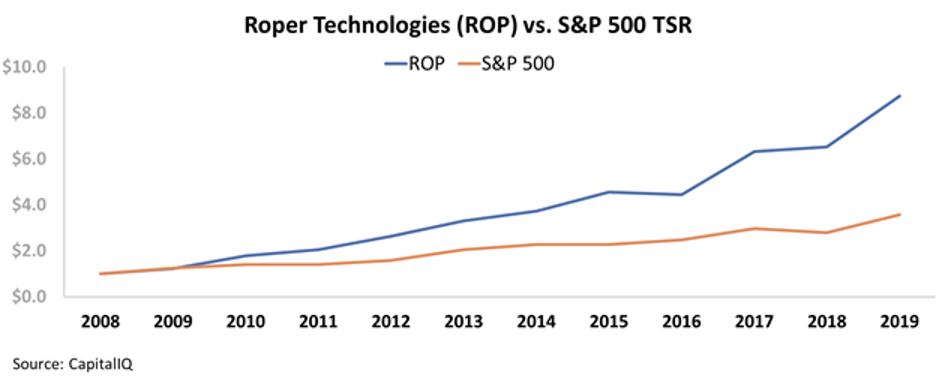

The strategy has already begun working incredibly well. As you can see in the chart below, Roper has more than doubled the TSR of the S&P 500 since the Great Recession.

However, when you dig into the company's financials, its fundamental performance looks average at best.

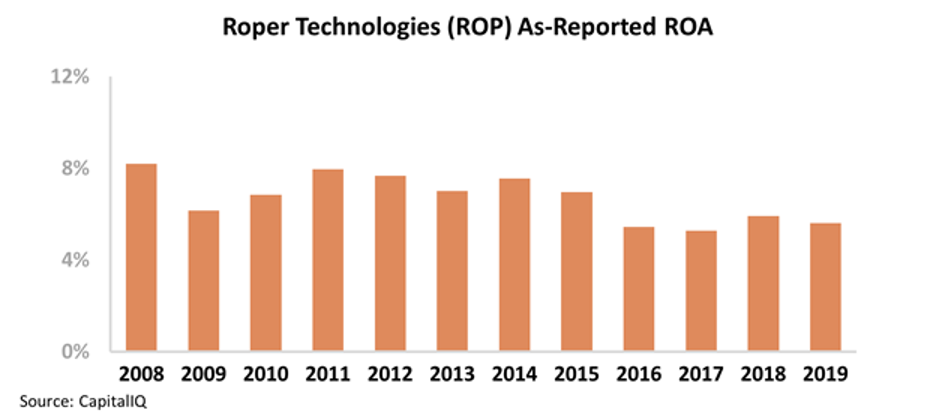

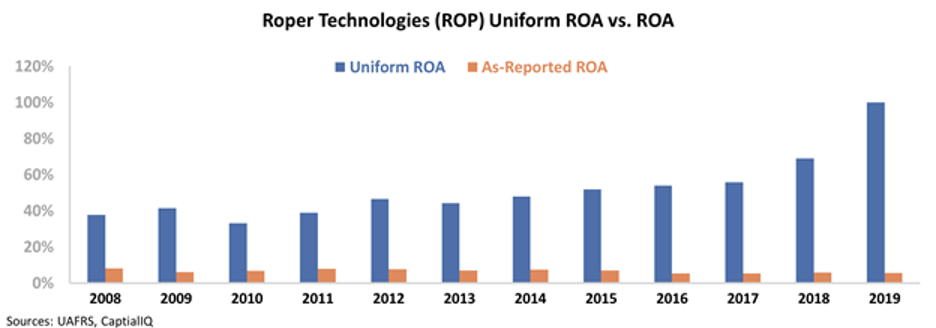

Since 2008, Roper's as-reported ROA has ranged between 5% and 8%, which is near long-term corporate averages.

If that were truly the case, the company would seem to be failing at its strategy – either by overpaying for decent companies or buying firms with less solid moats than Roper thought.

In either case, Roper's as-reported financials seem to conflict with its recent stock price... because the as-reported financials are wrong.

When we look at Roper using our Uniform Accounting metrics, we can find out what the market sees in the company.

After adjusting for misleading line items like the treatment of goodwill, research and development costs, and non-cash stock option expenses, we can see that Roper's true ROA is robust... and is getting stronger.

Even during the Great Recession, Roper maintained its Uniform ROA around 40% levels – more than six times long-term averages.

Moreover, Roper's Uniform ROA has expanded to a high of 100% in 2019, and it looks as though the company's returns are just starting to accelerate.

This may be the inflection point after which Roper takes off like Berkshire did back in the 1990s.

Even though the as-reported metrics don't seem to signal anything special about the company, the market is already reacting... and Roper isn't likely to slow down any time soon. It may indeed be an opportunity to buy the next Berkshire at the ground floor.

Regards,

Joel Litman

May 6, 2020

A sleepy corner of the Internet comes into full focus thanks to private equity and Uniform Accounting...

A sleepy corner of the Internet comes into full focus thanks to private equity and Uniform Accounting...