Gift cards may really only be a great gift to the retailers you buy them from...

Gift cards may really only be a great gift to the retailers you buy them from...

On October 11, we discussed how coffee giant Starbucks' (SBUX) innovation of venturing into the world of banking has led to the market rewarding the company with an impressive rally.

Thanks to its mobile app, Starbucks has built a significant amount of customer deposits – a massive $1.6 billion. It's basically a free loan to the business.

And thanks to customers forgetting about their balances – and the gift cards they have with the company – Starbucks can recognize some of that cash each year as revenue... even if customers never use it. It's called "breakage income."

As The Hustle reported last week, as we exit the holiday season, many people find themselves with a pile of gift cards. They're one of the most popular gift ideas in the modern era. It's not quite as thoughtless as writing a check... You're tailoring the gift card to what you know the user likes.

Starbucks isn't the only business that has a significant liability on its books for unused gift cards and also for other customer "deposits." Other names include major retailers like Walmart (WMT), Amazon (AMZN), and Target (TGT).

Thanks to rules on when this customer cash can be turned into revenue, based on the likelihood of it ever being used, these companies and many more are set up for regular 100% margin cash windfalls in coming years.

But that's unless you make sure to use your gift cards...

So be sure to gather up those cards and use them before you forget about them... and before that gift becomes free money for a company's investors instead!

It seems like a new 'micro' brewery is opening up every other day...

It seems like a new 'micro' brewery is opening up every other day...

That may not be an exaggeration, either – in the U.S., roughly 900 breweries opened up in 2018, which is about 2.5 per day. In fact, since 2014, the number of "craft" breweries in the U.S. has doubled.

While the craft beer industry seemed like it could have been a flash in the pan in the 1980s and 90s, by now, it's clearly here to stay. Smaller "micro" breweries continue siphoning volume away from the big "macro" breweries like Anheuser-Busch InBev (BUD) and Molson Coors Beverage (TAP).

Not only that, but craft breweries seem to be the industry trendsetters nowadays. Most bars and restaurants have just as many of those popular IPAs and sour beers as they have old-fashioned American lagers.

The resurgence of the craft mindset has also ushered in new optics for beer. It's no longer exclusively a cooler full of ice-cold blue cans at a tailgate... Beer is also "cellared" like a fine wine and paired with tasting menus at fancy restaurants.

As the high end of beer began looking (and tasting) more like wine, breweries began packaging their product like wine – with all kinds of bottles with corks and cages, dipped in wax and with interesting labels.

The days of simplicity and convenience were over. Cans became associated with the old guard of beer – far more a statement of function than quality.

However, the pendulum has shifted back the other direction thanks to one industry holdout – Oskar Blues Brewery.

In 2002, when it was nearly unheard of for craft beer to be found in cans, Oskar Blues chose not to follow the herd. After consulting its packaging supplier about the best way to store beer, Oskar Blues decided to become the first craft brewery to package all of its beer in cans.

The decision was simple – cans are easier to store and transport, they keep the product fresh longer, and they're better for the environment.

Despite the sound logic and science, the craft beer scene continued packaging in glass until the past few years, coinciding with the recent craft boom.

Amidst all of these changes in the beer industry, packaging suppliers are also affected.

One company in particular has adapted to the times, pivoting from its history as the first producer of the ubiquitous "crown" bottle cap to one of the biggest can makers in the world.

Crown (CCK) manufactures roughly 20% of the world's beverage cans and makes 50% of its revenue from those sales.

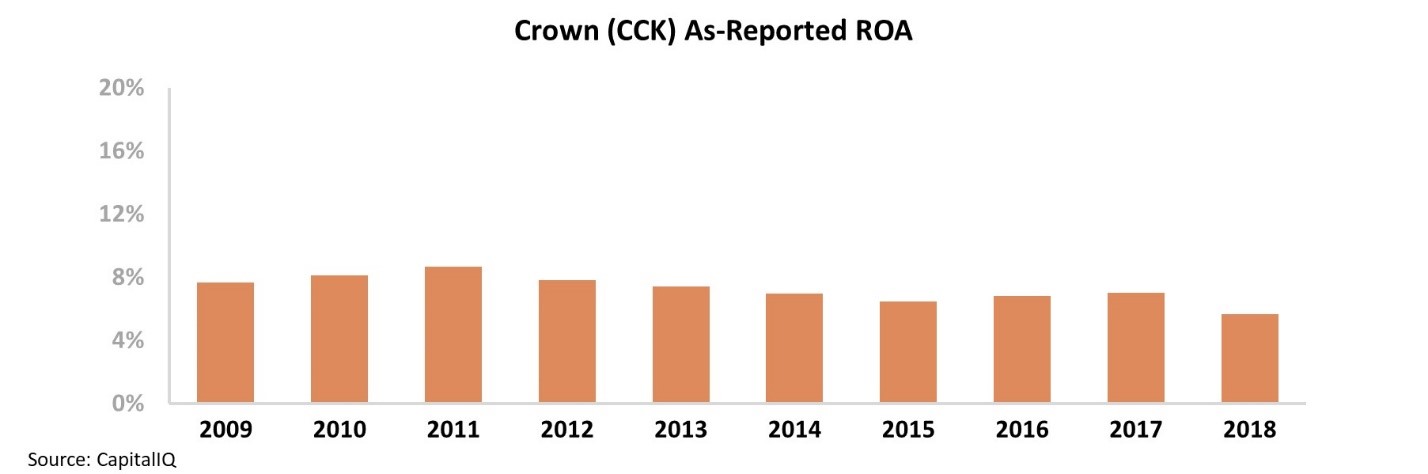

Despite its role as one of the main suppliers to the craft beer industry, the company has seen its returns come under pressure over the past decade. After enjoying returns as high as 9% in 2010 and 2011, the company's as-reported return on assets ("ROA") has crept back towards long-term corporate-average levels near 6%...

As craft brewers continued to prefer bottles over cans until recently, this isn't surprising. That said, it's puzzling why the resurgence of aluminum packaging over the past few years has not improved Crown's performance.

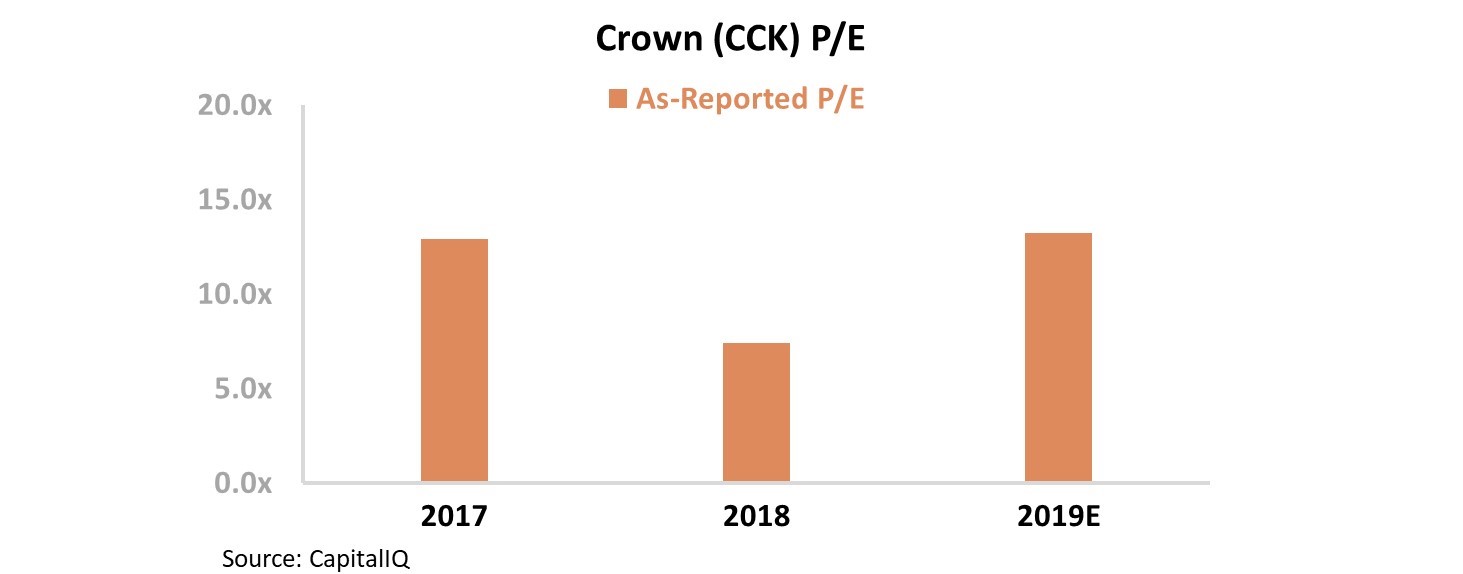

In the midst of recent headwinds, Crown appears to be undervalued compared with the market, with an as-reported price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 13 – well below market averages near 20.

Perhaps as aluminum packaging continues to accelerate, Crown would see an inflection... and this would be an opportunity to buy the company at a discount.

But in reality, Crown's profitability was not as disrupted as traditional metrics would have you believe... nor is the stock as cheap as most investors would believe.

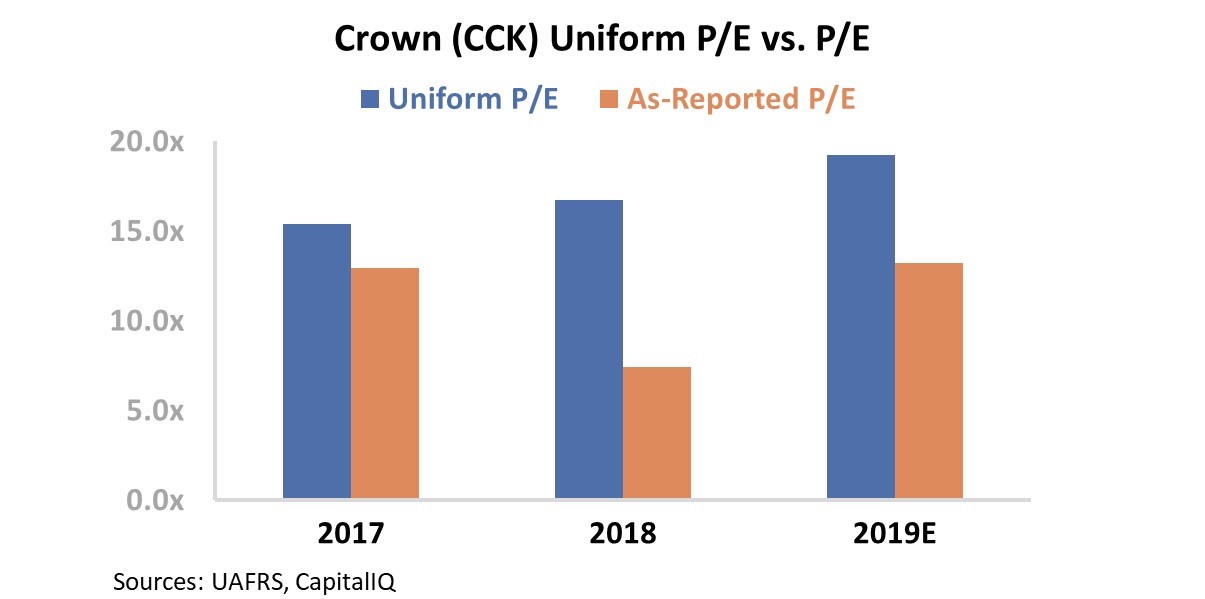

Once we apply our Uniform Accounting metrics – adjusting for inconsistencies like the treatment of goodwill, operating lease expensing versus capitalization, and non-cash expenses like amortization – we can see Crown's real profitability over the past decade.

While the company's Uniform ROA has been a bit more volatile – likely due to input prices – the larger takeaway is that profitability has not wavered over the last decade.

With the exception of 9% underperformance in 2013, Crown has maintained Uniform ROA above 10% since 2009 and has seen profitability improve since 2017. Take a look...

Moreover, although as-reported valuations make it seem like Crown is undervalued, in reality, the market recognizes that the company has seen stable profitability over the past decade. As you can see, Crown is in line with market averages. It sports a Uniform P/E ratio of 19.

At these levels, it appears investors have already priced in Crown's stable profitability. If you bought Crown today, you wouldn't be buying a mispriced company that's about to see a resurgence like as-reported financials imply.

In reality, you'd be buying a company with stable returns and reasonable valuations. That doesn't sound as compelling... but using the true numbers can help you avoid a value trap.

Regards,

Joel Litman

January 10, 2020

Gift cards may really only be a great gift to the retailers you buy them from...

Gift cards may really only be a great gift to the retailers you buy them from...