In 2010, one of the most infamous events in stock market history occurred...

In 2010, one of the most infamous events in stock market history occurred...

A little after 2:30 p.m. on May 6, the stock market began to crumble. The Dow Jones Industrial Average was already down 3% on the day... and in a matter of minutes, the index lost another 6%. Investors panicked... but by shortly after 3 p.m., the Dow regained most of the drop.

It may have only been 30 minutes, but for those in the market, it felt like a lifetime.

This incident is now known as the "2010 Flash Crash." In that half-hour period, $1 trillion of value was destroyed and then recreated. And it was partially caused by "spoofing"...

This is when a trader creates fake demand. For example, if a trader wants to buy a certain stock, he'll put in a buy order. Then, the trader can "spoof" the market by putting in a large amount of sell orders. Upon seeing the influx of sell orders, algorithmic trading systems will continue the momentum, as they believe that stock's price is on its way down.

However, the sell orders are only a ruse. The algorithms will push the price of the stock down, allowing the trader to buy shares at a depressed price.

This is what happened in the 2010 Flash Crash, only on a much larger scale. When some massive spoofing trades occurred, algorithms and high-frequency traders came in and caused the market to nosedive.

Most investors generally associate flash crashes with equity or derivative markets. However, the same practice happens with commodities like gold...

As Bloomberg recently explained, spoofing has become commonplace on commodity trading desks for some of the largest banks in the world. Specifically, the U.S. Department of Justice ("DOJ") has accused JPMorgan Chase (JPM) of operating a "crime ring" on its precious metals trading desk.

The DOJ claims that since JPMorgan consumed Bear Stearns, the firm's traders have used spoofing to aid the trading desk's profits... It's a desk that makes $250 million annually.

JPMorgan is set up to pay upwards of $1 billion in penalties for the activity, as it will have stolen millions from those trading on the other side of the market.

Many folks invest in gold and other metals due to their reputation as safe assets that can't be distorted by Wall Street's games. However, as this case highlights, the commodity market is at just as high a risk of being distorted as any other asset class.

Some of the people on the wrong side of those trades were looking for anything but a speculative investment...

Some of the people on the wrong side of those trades were looking for anything but a speculative investment...

This is because they use the trades as a hedge against risk. For every JPMorgan trader looking to make money on speculative trades, the other side is often looking to lock in profits.

Gold miners use futures to hedge the price of gold. To gain visibility on future cash flows, the miners will sell gold futures to "lock in" a sell price. This protects them from volatility in the gold market. Even if the price of gold falls, their production can be sold at a consistent price. However, the gold miners also won't make more money if the price of gold goes higher.

When those gold miners are hedging in the midst of market manipulation, they're locking themselves in to make less money on their actual day-to-day production.

One miner that doesn't take part in this process – perhaps to avoid being spoofed – is Agnico Eagle Mines (AEM). Agnico has production across Canada, Finland, and Mexico. It dabbles in many commodities, but it's most active in the gold sector.

Agnico always chooses to "ride" the market rather than hedge. Because of this, investors could reasonably expect the company's profitability to move with the price of gold.

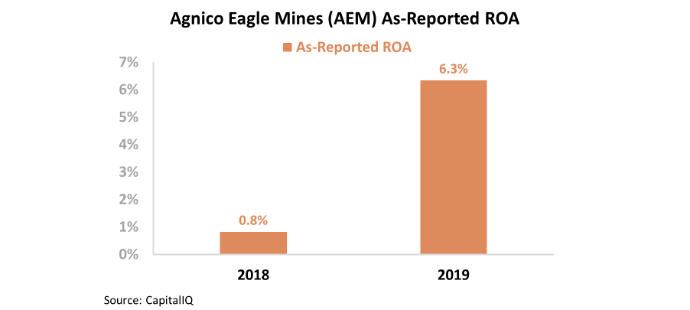

Last year, the price of gold began to rise from less than $1,300 per ounce in January to $1,550 per ounce by the end of the year. As such, it's no surprise Agnico's return on assets ("ROA") appears to have inflected higher in 2019.

The company's as-reported ROA was just 1% in 2018, before rising to 6% in 2019. For a gold miner, this was a significant jump in profitability.

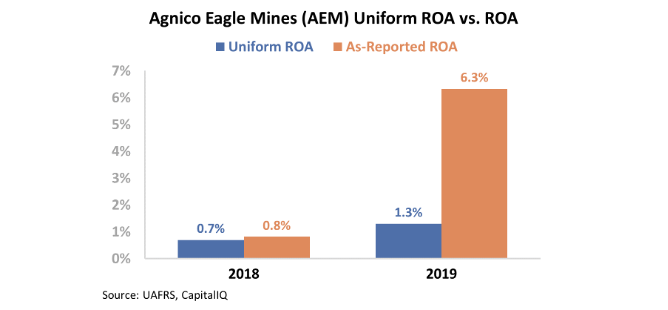

However, this isn't an accurate depiction of Agnico's returns. GAAP's treatment of property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) – among other distortions – is making Agnico appear to be more profitable than it is.

In reality, the company's profitability levels did not budge in 2019. Agnico's Uniform ROA was 1% in both 2018 and 2019. Take a look...

Uniform Accounting shows that, much like investors on the other side of a JPMorgan gold trade, Agnico investors have been duped. Even with the rise in gold prices, Agnico had to ramp up expenses at a similar pace. This meant the company didn't see much profitability improvement.

This year, gold prices have continued to climb due to market uncertainty... and continuous gold contracts are currently near $1,900 per ounce. This means that expectations for Agnico's stock are steep. To evaluate these expectations, we can use the Embedded Expectations Framework.

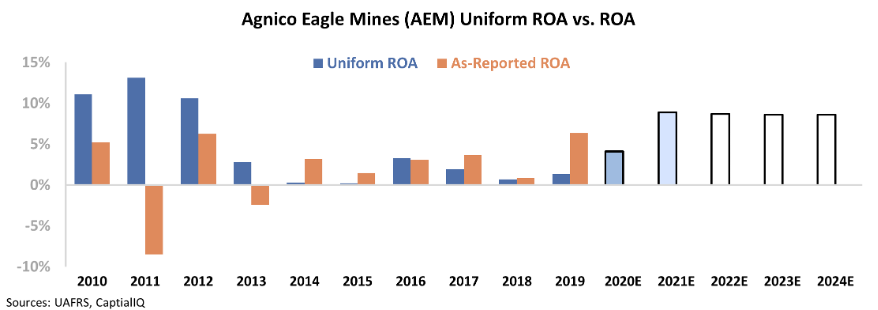

The chart below explains Agnico's historical corporate performance levels, in terms of ROA (dark blue bars) versus what sell-side analysts think the company is going to do in the next two years (light blue bars) and what the market is pricing in at current valuations (white bars).

Sell-side analysts are forecasting the company's ROA to reach 4% this year, before rising again to 9% in 2021. Then, the market is pricing in returns to maintain 9% levels through 2024.

Agnico hasn't been able to sustain profitability levels that high since 2012, when gold prices reached a short-term peak.

Therefore, investors who want to use Agnico as a vehicle to invest in rising gold prices may want to think twice... While elevated gold prices will help the company, this is already priced in. Anything less than sustained high gold prices would hurt AEM shares.

With gold prices near highs, investors may think that now is a good time to invest in Agnico. However, the company's expectations are near record highs... and the elevated price of gold is already priced in.

This stock is yet another example of how, even in commodities, financial markets can trick investors who don't understand the real profitability metrics.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

October 14, 2020

In 2010, one of the most infamous events in stock market history occurred...

In 2010, one of the most infamous events in stock market history occurred...