In order to boost returns, this popular home-goods retailer is looking beyond operational strategies...

In order to boost returns, this popular home-goods retailer is looking beyond operational strategies...

Yesterday, Bed Bath & Beyond (BBBY) announced it had completed a sale-leaseback transaction with private-equity firm Oak Street Real Estate Capital, bringing in $250 million in proceeds.

Bed Bath & Beyond has seen its Uniform return on assets ("ROA") fall from 15% in 2012 to a forecast negative 2% for fiscal year 2020. Considering this decline, the company is looking for any reasonable way to raise cash while also boosting profitability.

The changes in U.S. GAAP and IFRS around how leases have been treated on balance sheets over the past several years generated a lot of attention. Operating leases, which had previously only showed up on a company's income statement, would now also appear on the balance sheet.

This was meant to better represent the economics of a company's decision to lease or own its assets. Both were fundamentally about the business gaining access to the same set of assets... But one would punish the balance sheet more.

Buying property, plant, and equipment ("PP&E") requires an initial investment, but it grants total control of the asset and its value to the company and shareholders in the future. Leasing enables a company to spread those payments out over time, but also not have true ownership of the asset.

Leasing an asset instead of owning it is a financing decision. And with leases now being brought onto the balance sheet, investors can now see through that financing decision when analyzing a company's operating performance.

In reality though, as-reported accounting hasn't improved at all in seeing through this noise.

In the case of Bed Bath & Beyond, its asset base will shrink after this transaction... even though the company is still operating the same stores in the same way. It's just leasing them instead of owning them. If the accounting had been fixed, Bed Bath & Beyond's balance sheet wouldn't have changed at all.

This is because of how operating leases are capitalized – over the life of the lease instead of the life of the asset that's being leased. So if Bed Bath & Beyond has shorter leases, the value of the stores on its balance sheet is less than it would be if the company had longer leases or still owned a store outright.

By making this decision, Bed Bath & Beyond has benefited shareholders by raising capital... but has also distorted its returns even more. The company is trying to reverse its operating trend in any way possible – through both real operational and artificial financial efforts.

Fortunately, using Uniform Accounting, we can see through that noise and realize where Bed Bath & Beyond's returns are really trending.

In 2017, I had the good fortune of speaking at Ayala's Innovation Summit in Manila...

In 2017, I had the good fortune of speaking at Ayala's Innovation Summit in Manila...

The meeting featured a number of innovation experts from various backgrounds and industries serving as panelists. They were evaluating several "teams" presenting multiple months' worth of work and research into various value-adding innovative ideas.

One of the panelists was Avinoam Sapir, who serves as a leader of innovation for Teva Pharmaceutical Industries (TEVA) in Israel. It was great getting to hear him speak and to talk to him one-on-one about the pharmaceutical industry.

Despite being an Israeli company, Teva makes most of its revenue in the U.S. A big reason for that is the unique dynamic that exists in the American pharma industry...

You see, the U.S. is one of the only countries in the world that allows pharmaceutical companies to advertise. And if you've ever watched TV, read a magazine, or listened to the radio in the U.S., I'm sure you're familiar with the advertisements I'm referring to.

And not only is the U.S. among the most lenient countries for drug advertising... it's also among the most lenient when it comes to drug pricing.

This is in part due to the extended patent lives for pharmaceuticals in the U.S. It creates small pockets of monopolies for companies as long as their drugs are still under patent, effectively allowing them to charge whatever they want.

Given that the U.S. is unlikely to seriously reform the pharmaceutical system to resemble something like that of the U.K. or Germany, some companies have taken it upon themselves to innovate within the confines of the free market.

After a drug's patent has run out, other drug companies are able to bring replica versions of that drug to market. As is true with most competition, this has the effect of lowering the drug's price for everybody.

These replica drugs are often referred to as "generics" because they can't carry the original brand name of the patented drug. This is a much larger phenomenon outside the U.S. because drugs have far less patent protection.

And Teva is the global leader in generic drugs.

While the company also manufactures a series of specialty medicines, its main source of revenue is generics – meaning it's bound to be a far less profitable company than a branded pharmaceutical firm.

Inherently, generic drugs directly compete with their named counterparts – and must be priced lower as a result. Because Teva makes a majority of its revenue from lower-priced generic drugs, its profitability tends to be lower than a brand-name manufacturer.

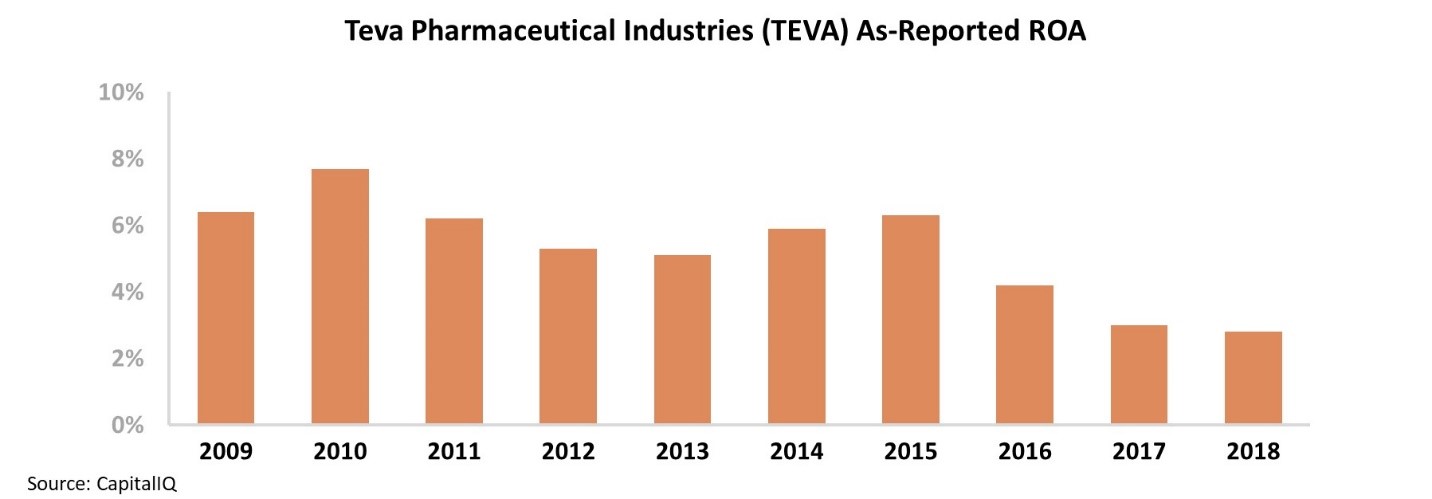

Over the last decade, Teva's ROA has remained fairly weak – near long-term corporate averages. Moreover, since 2016, the company's ROA has fallen to a low of just 3%...

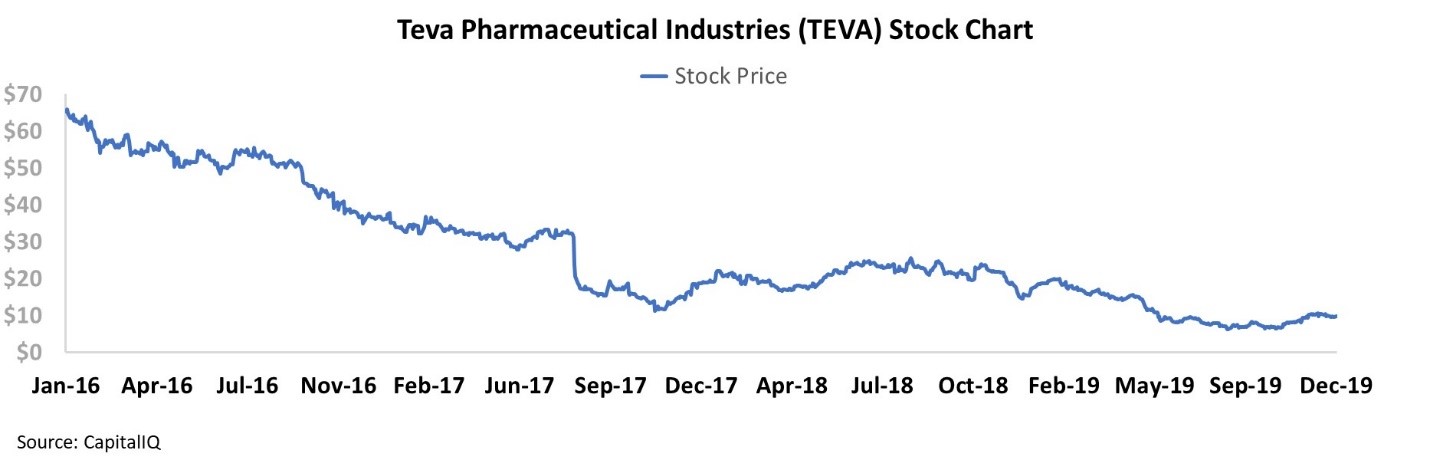

In line with its recent profitability trends, Teva's stock has been under pressure because the future of the pharma industry in the U.S. has been uncertain. Look at the decline over the past four years...

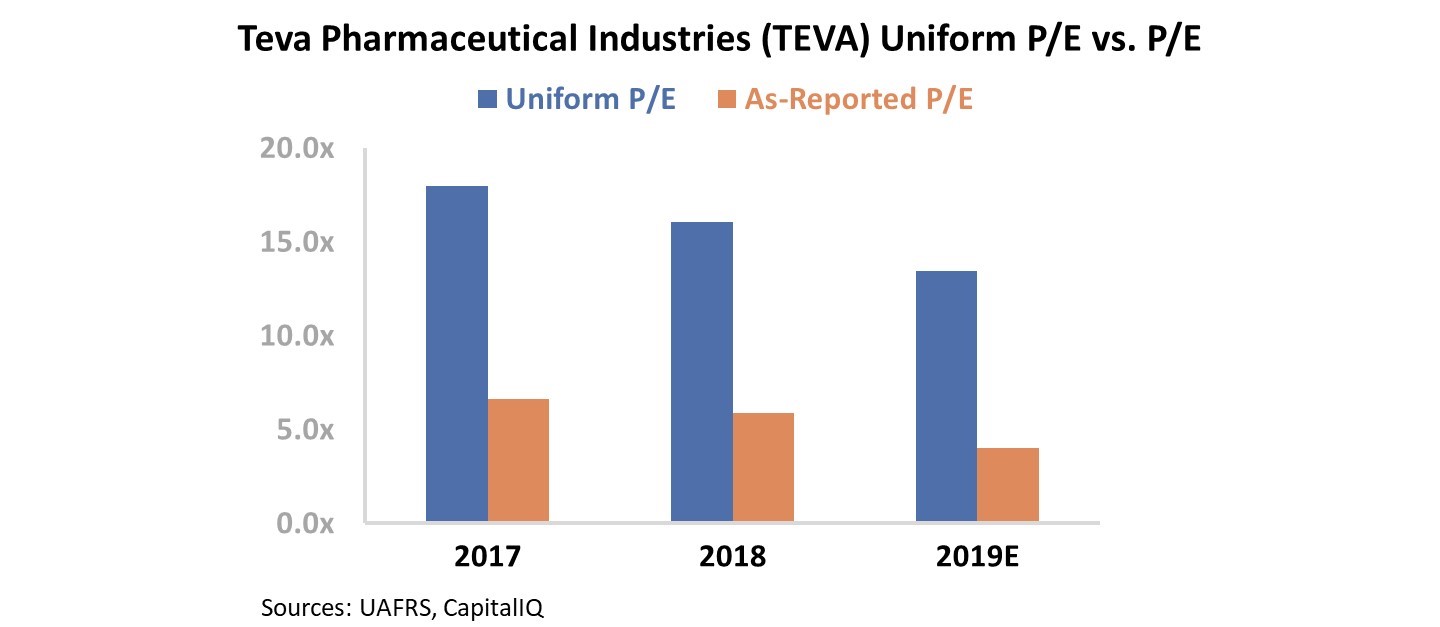

Meanwhile, this has driven valuations to levels we rarely see. On an as-reported basis, Teva's price-to-earnings ("P/E") ratio is 4, well below industry averages and considerably below market-average levels near 20 times. Take a look...

At these levels, expectations for Teva appear to be incredibly low. However, this may not be the case once we look at the company using Uniform Accounting metrics...

For a business like Teva, we need to adjust for the impact of items like goodwill and capitalizing versus expensing research and development ("R&D") and operating leases to see its real valuations.

Once we make the proper adjustments, we can see that – while still less expensive than the market – Teva is not as cheap as it appears on an as-reported basis...

In reality, Teva trades around 14 times earnings. While this may still seem like an interesting opportunity given that this is less expensive than the market, the company looks far less compelling when you compare it with the other major generic and branded pharmaceutical companies...

Given the nature of these businesses, it makes sense why these companies would trade at a slight discount to the market... They're either competing in the generic space or are perpetually at risk of losing their premium cash flows as a branded pharmaceutical company being threatened by the generics.

Any business would look cheap at 4 times earnings. But without Uniform Accounting, you might think you were getting this company at a steal of a price. In reality, you're not.

Regards,

Joel Litman

January 7, 2020

In order to boost returns, this popular home-goods retailer is looking beyond operational strategies...

In order to boost returns, this popular home-goods retailer is looking beyond operational strategies...