Dear reader,

As cliché as it may sound, change is important for long-term corporate performance...

Japanese video-game giant Nintendo (NTDOY) began its life as a playing-card company in 1889. After a successful 75-year run, the company began experimenting with new business lines. The card business was declining, so the company took what it learned from its successful partnership with Disney (DIS) and entered the toy market in 1966.

Following a few years of testing, Nintendo found traction in the budding electronic games market, and the rest is history... Imagine if the company had stuck with playing cards.

French carmaker Peugeot (PUGOY) was founded under Napoleon's regime as a small engineering firm. For the first 80 years, the company manufactured mostly small steel objects like coffee grinders, umbrella frames, and eventually bicycles. In 1889 – the same year Nintendo made its first deck of cards – Peugeot made its first steam-powered three-wheel vehicle.

Vehicles began as more of an experiment of passion for Peugeot, but soon proved to be a sustainable venture. Five years later, the company built the winning car in the Paris-Rouen – the world's first motor race – with its staggering 3 horsepower engine. Again, the rest is history.

Some of the oldest companies still in operation today have gone through complete life cycles.

For these businesses, reinvention was the key to longevity. They needed to change... or die.

Today, IBM (IBM) is the poster child for corporate reinvention. Similar to Nintendo, the company was founded before the electronic revolution.

Its first competency was basic record-keeping. Punch cards, time recorders, and simple tabulating machines allowed companies to record data at unprecedented speeds.

You could find IBM products in just about every business by the 1950s, which gave the company plenty of capital to invest in research and development ("R&D") for its first major reinvention.

IBM was one of the first players in electronic computing technology. In the 1960s, it created the industry standard for mainframe computers, an advantage IBM maintained until the 1980s when personal computers really entered the market.

By this time, IBM was affectionately nicknamed "Big Blue" after its blue computers. It was the perennial "comeback kid" that could always reinvent itself. Despite struggling into the early '90s, IBM was still a Wall Street sweetheart.

As legendary money manager Peter Lynch wrote in his book Beating the Street...

Although a dreadful stock in many ways, no fund manager has ever been fired for buying IBM: it is said that IBM has "disappointed the market," not that the fund manager screwed up.

But IBM has failed to find its new phase since then. The problem is that the company isn't investing in R&D the way it used to...

Historically, IBM has taken its excess funds and invested them in new research to fuel its reinvention strategy. However, in recent years, management has favored another use of the company's capital...

Lining its checkbooks. You see, IBM management figured out how to game the system.

For most public companies, executive-level managers are paid based on incentive compensation. For example, only 8% of IBM CEO Ginni Rometty's total compensation is from her base salary.

Another 23% of her salary is paid in what are called "time-based incentives." This means that as long as she is with the company, this incentive compensation "vests" over time and she receives IBM shares. The remaining 69% of her salary is incentive-based.

Incentive-based compensation is a bonus that is tied to specific metrics or goals. If a company achieves those goals, management gets paid. And IBM's board of directors has a subcommittee that determines what metrics management should be compensated for.

Here at Altimetry, we also study management incentives. We believe that it is just as important to understand how management is paid as it is to understand the Uniform Accounting metrics for a company.

Not how much they are paid... but how they are paid.

Management team members are people, and people tend to do what they are paid to do. If the board sets a goal for executives to reach their bonuses, management will steer the business to get to those bonuses.

We analyze management incentives by looking at a special filing that many people don't pay attention to... the DEF 14A, or the annual proxy. In this form, the company has to disclose what the key metrics are for management to reach their bonuses.

Over the past two-plus decades, IBM management has been compensated almost entirely based on earnings per share ("EPS"). This typically measures a company's net income divided by the number of shares outstanding.

This is concerning for two reasons... First, as regular readers know, as-reported earnings are unreliable and unrepresentative of a company's real performance. And second, EPS is easily manipulated.

There are two ways for IBM executives to improve the company's EPS: grow earnings, or shrink shares outstanding.

As we mentioned, the company has struggled as it has reached the end of the life cycle of its latest wave of innovation. Even with its Watson investments, IBM was no longer the computing powerhouse it was in the 1970s, so there was no easy way to massively grow its earnings.

Management couldn't grow earnings to grow EPS, so it did exactly what it was being paid to do: Shrink the company's total shares outstanding. Since 1995, IBM has spent an astonishing $200 billion on stock buybacks.

Since the Great Recession alone, the company has repurchased more than $83 billion in stock. Shockingly, this has not been the reinvention investors had hoped for.

Over the same period, IBM shares are roughly flat.

Investors pay for performance. As companies continue to grow and improve their profitability, the market tends to reward this type of activity.

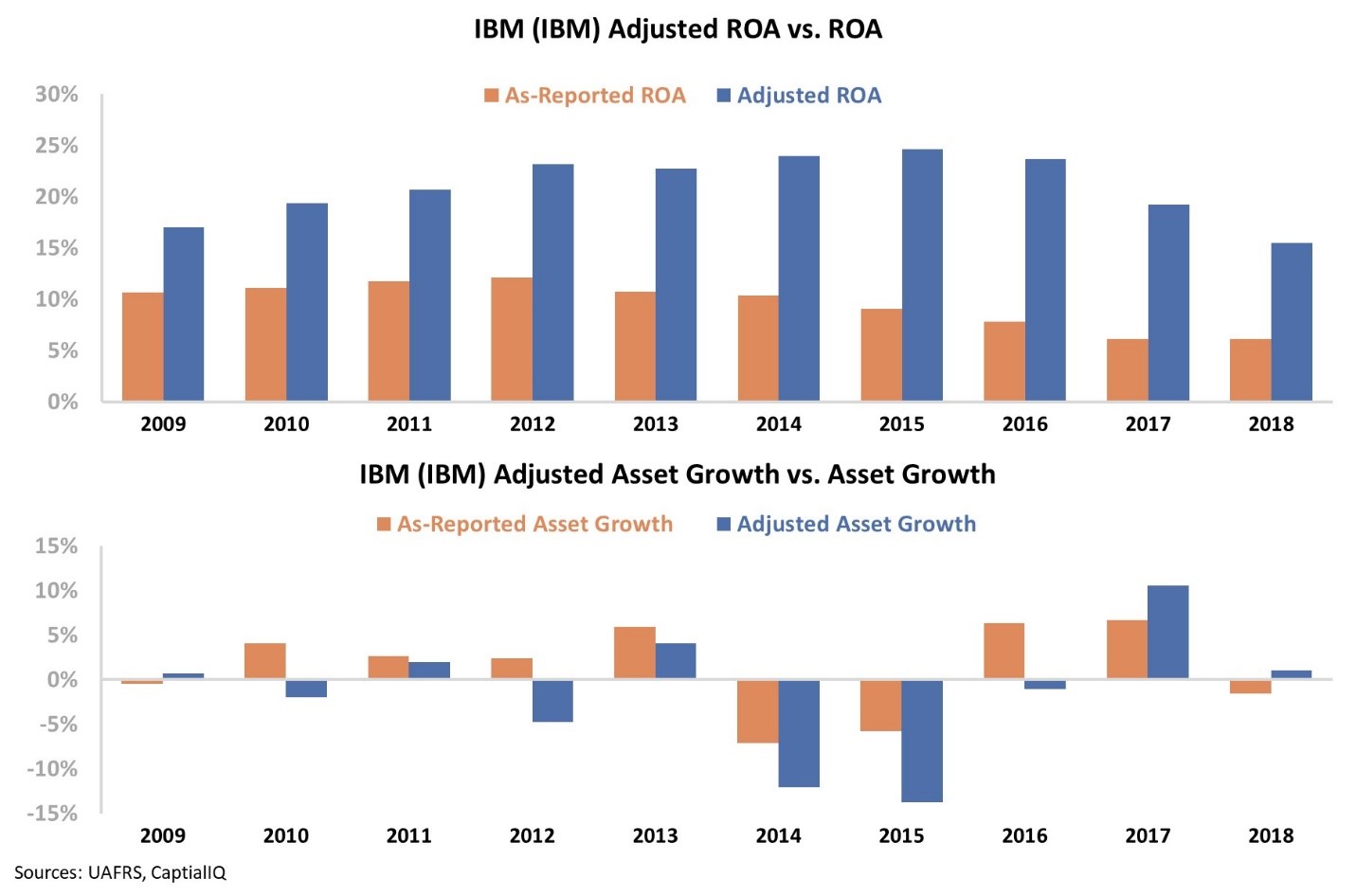

Despite maintaining a decent return on assets ("ROA") over the last decade, IBM has failed to grow, as most of the company's excess cash has gone toward share buybacks. Take a look...

IBM has shrunk its asset base in five of the last 10 years. For a company with such a rich history of leading the tech industry and consistently reinventing itself, it's puzzling – and a bit sad – to see what IBM has become.

When all is said and done, corporate executives will always do what they are paid to do. While IBM recently removed the impact of share buybacks from management compensation, its executives are still compensated based on EPS.

When management is paid to produce a metric that has nothing to do with real corporate performance, it's not surprising to see investors head for the exits.

Regards,

Joel Litman

October 30, 2019