Former Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker waged a ruthless war on inflation...

Former Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker waged a ruthless war on inflation...

Volcker was the Fed's top dog from 1979 until 1987 – one of the highest-inflation periods in U.S. history. And he's widely credited with getting prices back under control through a series of bold policy moves.

Former President Jimmy Carter specifically nominated Volcker because he wasn't afraid to get his hands dirty to curb inflation, which was at 13% the year Volcker was appointed.

Interest rates are the best tool any Fed chair has to impact inflation and growth. (Specifically, the Fed controls the short-term federal-funds rate.) Raising interest rates curbs inflation by slowing down borrowing, economic activity, and sometimes even employment.

When Volcker took over, the federal-funds rate was already a whopping 11.2%. That's way higher than it has been at any point since 1984.

Volcker knew raising rates further would likely hurt the economy. But it was the only way to get inflation under control. So he did what he felt was necessary. He raised rates to a record 20% in 1980.

His choice had two major consequences...

His choice had two major consequences...

First, within a year, inflation fell below 10%. And by 1983, that number was down to about 3%. That's what Volcker wanted.

But in the process, a second outcome occurred. By raising rates so high, Volcker sent the U.S. economy into a two-year "double dip" recession. Unemployment rose above 10%. It was a particularly "hard" landing, to use the common terminology.

Fast-forward to today, and folks are quickly cooling on the idea that we'll get a "soft" landing this time around. Much like Volcker, current Fed Chair Jerome Powell is using interest rates aggressively. He just issued his third consecutive 75-basis-point hike, bringing the federal-funds rate between 3% and 3.25%.

That's a lot lower than what Volcker was dealing with. But remember that the federal-funds rate was basically zero when Powell started interfering.

And it doesn't end there. The market expects additional rate hikes will bring interest rates to 4.5% by the middle of next year. Investors don't think rates will start to come down until 2024.

A 4.5% hike in what amounts to a year is staggeringly quick. And the effects have shown up in a lot of places...

Mortgage rates are at levels not seen since 2008. The average yield on "junk" bonds hasn't been this high since 2012, right after the Great Recession and in the midst of the European debt crisis. Bank credit-lending standards are tightening aggressively.

And the central bank estimates unemployment to rise from 3.7% to 4.4% by next year. That could cost more than 1 million jobs.

Still, the consequences could be worse if inflation goes unchecked.

Like Volcker in the 1980s, Powell is doing whatever he can to stamp out inflation – even if it means hurting the economy...

Like Volcker in the 1980s, Powell is doing whatever he can to stamp out inflation – even if it means hurting the economy...

The situation has everyone on edge, and rightfully so. There doesn't seem to be a quick fix for inflation.

Consumer prices have seen the largest one-year jump in 40 years. And these numbers don't look like they're coming down anytime soon.

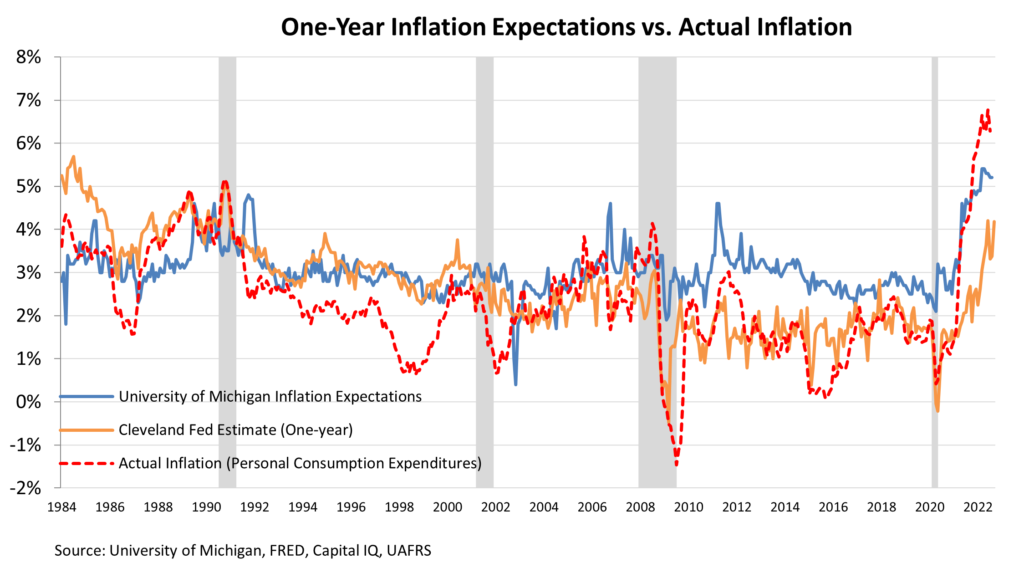

To get a better idea of where prices could go next, we can look at the University of Michigan inflation expectations. These projections, which have been issued since 1984, tend to closely follow actual inflation.

The University of Michigan's one-year inflation expectation for 2023 recently rose to 5%.

Check it out...

It looks like short-term inflation is here to stay, at the very least. This will lead to more wage hikes and increased spending. The combination will contribute to continued spiraling inflation.

This is exactly what the Fed needs to quash.

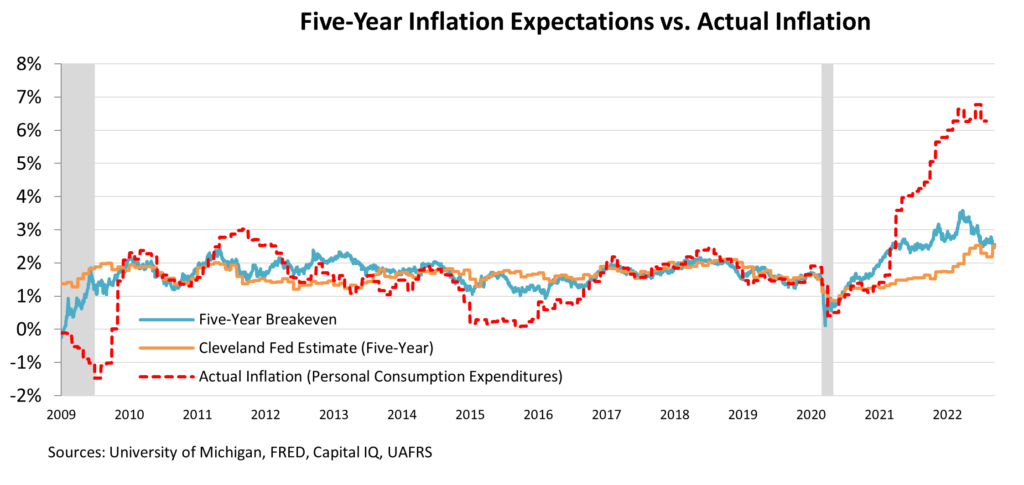

Fortunately, longer-term projections paint a rosier picture. The University of Michigan's five-year inflation expectations sit around 2.5%. This is higher than the sub-2% levels of the past 11 years. But it's still lower than the 3% expectations we saw earlier this year.

Take a look...

Based on this data, the Fed's actions seem to be working to ease long-term inflationary pressures.

For now, Powell is going full-steam ahead in his war on higher prices. But the Fed will be on the lookout for declining intermediate inflation expectations... and for current inflation to fall.

That's when the central bank will know to ease its foot off the gas pedal.

Regards,

Joel Litman

October 10, 2022

Former Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker waged a ruthless war on inflation...

Former Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker waged a ruthless war on inflation...