Dear reader,

There's real estate, precious metals, natural resources, municipal bonds, and a litany of other "alternative assets" out in the markets.

I often get questions about why our firm spends so much time looking specifically at stocks and bonds. There are so many other asset classes that can help diversify an investor's overall portfolio.

All things considered, we have determined stocks and bonds provide sufficient diversification and the best risk-adjusted return out of any combination of asset classes.

However, this doesn't stop people from asking about the latest fad...

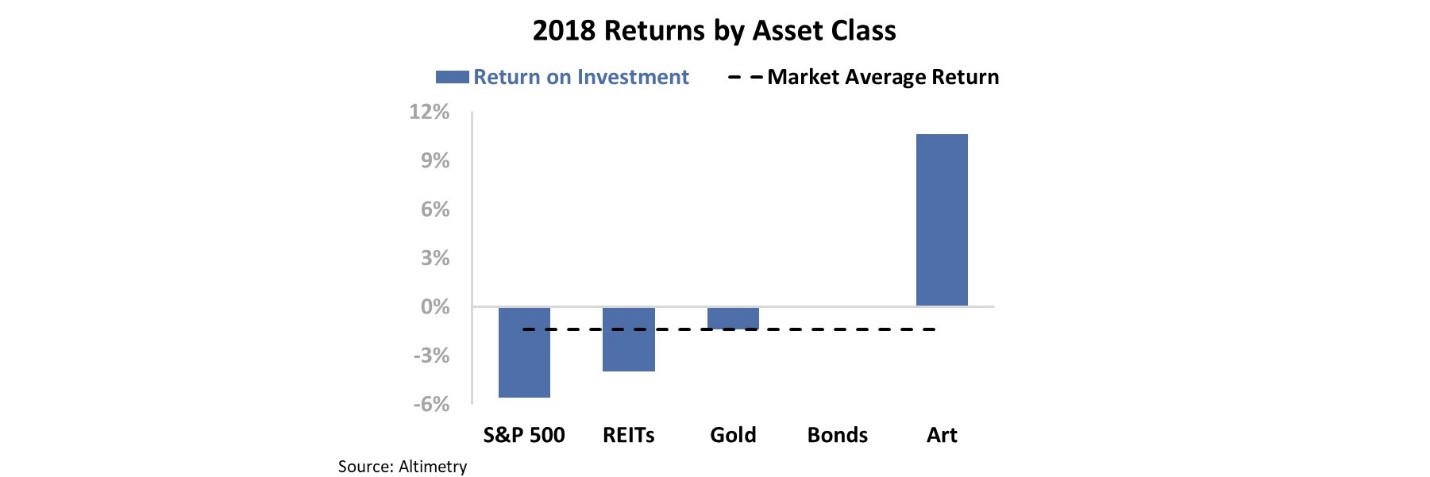

I recently had a shocking discussion with a colleague. He claimed art was among the best-performing asset classes last year. Now, 2018 was a tough year for investors. So when I dug into the numbers, I almost didn't believe them...

In 2018, the art asset class returned 10.6% compared with 5.1% for the S&P 500 Index, -4% for real estate investment trusts ("REITs"), -1% for gold, and 0% for investment-grade bonds.

But it was true. There were some blockbuster art sales in 2018. From Matisse to Monet, and Picasso to Edward Hopper, some truly incredible art pieces changed hands last year... not to mention for some incredible premiums.

Jean-Michel Basquiat's "Flexible" sold for $45.3 million, more than twice the low end of the $20 million estimate art auctioneer Phillips provided.

After stewing over these numbers, I had to take a moment to think... Should I forget about my career in traditional asset classes and bet the farm on art?

The answer might surprise you...

No. Unequivocally, no.

There's a huge bias in the way art returns are calculated. And this bias has multiple implications on my opinion of the art market.

The key is liquidity.

The huge sales from 2018 I mentioned above represent just a fraction of all sales in the art market. In total, there were 39.8 million lots sold in 2018.

And that doesn't even reflect all the untraded art. Pieces that remain in "freeport" storage facilities in Geneva and Luxembourg or on peoples' walls aren't part of this "return" calculation.

It's difficult to estimate the total number of lots in the world, but consider this: The permanent art collection in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art consists of more than 2 million pieces. The Hermitage in Saint Petersburg contains more than 3 million works.

These two museums alone contain more than 5 million potential lots. With roughly 2,500 dedicated art museums in the U.S. alone, thousands more around the world, and the countless private collections that fall between the cracks... it's obvious that only a fraction of all art is actively traded in any given year.

Compare this with the stock market. Tech giant Apple (AAPL) alone trades more than 32 million shares every day. That's one company – on one index – in one day.

Annual art sales are not representative of the broader art market.

First, the 10.6% return cited in 2018 assumes all the art not sold last year also appreciated 10.6%. It's foolish to think that's the case – there's a reason the art that did sell, sold. These pieces were in demand.

Saying the art market was up 10.6% is like saying the stock market was up 62% last year because you only care about the performances of big movers like TripAdvisor (TRIP), Square (SQ), Chipotle Mexican Grill (CMG), and Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) in the last year – these companies' average returns were 62%.

Second, the art market is heavily skewed by the largest gainers. You can even do this analysis within one particular artist...

Let's take Picasso, for example. His works, on average, return about 5.1% annually before maintenance and transaction costs. One of the versions of Picasso's "Les Femmes d'Alger" is the ninth-most expensive painting of all time, selling for more than $179 million in 2015.

But I want to talk about another of Picasso's works... "Tête d'homme."

Depending on how much you know about art, you may or may not know Picasso created several works titled "Tête d'homme," or "Man's Head."

When looking at the last two transactions for "Tête d'homme," the results are frankly quite revealing about the deception in that 10.6% figure...

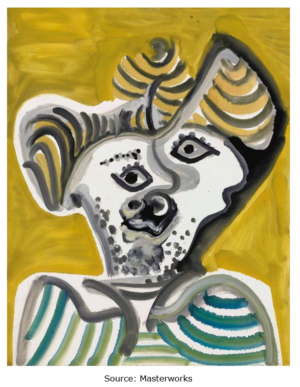

Below is one of the "Tête d'homme" pieces, painted in 1972 and sold in 2014 after a 25-year holding period. The original purchase price was $117,600 and the sale price in 2014 was a whopping $4,213,439... That's a 16% annual growth rate for a 3,570% total return. This is Picasso's second-highest returning piece of all time.

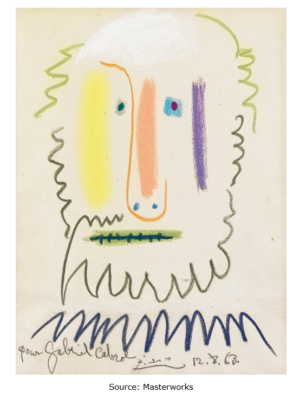

Below is another "Tête d'homme" piece, created nine years earlier in 1963. The work was purchased in 2005 for $98,172 and sold seven years later for just $126,549... That's less than 4% annual growth and only a 29% total return.

Considering Picasso created some of the highest-value paintings of all time, it's astounding the range of returns his works have commanded. He is said to have created nearly 50,000 pieces in his lifetime.

Remember that 5.1% annual return figure? Imagine how low Picasso's average returns are when considering maintenance, transaction costs, and all of the pieces that have never been sold.

Many investors talk about the potential of alternative assets to boost returns. However, the statistics that are quoted on the returns of these assets are often as bad as as-reported accounting is at showing corporate performance.

At the end of the day, the liquidity and depth, ownership of real cash flow generation, and long-term upside potential of the equity markets is the reason this is the premier destination for investors.

It's important to have all the facts when making an investment decision. Much like when we adjust as-reported financial statements to reveal a company's real returns, when we adjust the as-reported return for the art asset class, it doesn't look nearly as attractive.

Regards,

Joel Litman

October 14, 2019