As the old joke goes, put two economists in a room and you'll get three opinions on the economy...

As the old joke goes, put two economists in a room and you'll get three opinions on the economy...

Last Monday, we highlighted a concern over both credit and equity markets from Bob Prince of Bridgewater Associates. Prince was concerned the risk of inflation could cause the Fed to raise interest rates, leading to a potential collapse of bond prices.

This macroeconomic trend would pressure high-yield bonds as a group. Therefore, it's no wonder many experts are concerned about current optimism in the market.

However, Bradley Sullivan, a senior portfolio manager at State Street, has a different opinion.

Sullivan, an expert trader in the space, is of course "talking his book" when he goes against negative opinions on the high-yield space. And yet he does highlight compelling reasons to believe attractive trades are still available.

Sullivan has highlighted how the high-yield credit space has been completely upended over the past six months. The high-yield debt market has grown by 8% from new debt issuances, as companies look for capital to weather the storm. Furthermore, once-investment-grade companies have slid to high-yield status at an impressive rate – they are what industry experts dub "fallen angels."

Through all this, high-yield bond spreads are still wide relative to history, suggesting some upside for smart investors. The companies that have gotten re-rated as fallen angels in 2020 are ineligible for investment-grade funds to own and tend to become oversold.

This means investors willing to sort through the high-yield space could be able to exploit a market inefficiency many institutions will be unable to. Investors who know which bonds are oversold could see outsized returns, as the price of these bonds would soon bounce back after these investment grade funds finished their forced selling.

Clearly, there is still a large disagreement over the health of credit markets. However, despite the risks in the market as a whole, there is still opportunity for smart buying within the space. And part of that is because if you don't wait for what the credit-rating agencies say, you can be ahead of the pack.

This is because credit-rating agencies have a notoriously 'tortoise-like' reputation in how they operate...

This is because credit-rating agencies have a notoriously 'tortoise-like' reputation in how they operate...

These agencies are well-known for the failure to properly evaluate subprime mortgage securities during the Great Recession.

In some instances, the rating agencies have not downgraded troubled debt securities until just before bankruptcy. In 2001, Enron's credit rating remained at investment-grade just four days before bankruptcy, despite its massive decline in share price.

Another issue is how credit agencies just refuse to ever view some industries as investment grade, no matter how good a company is. An example of that is Mirant, a company we pounded the table on back in 2009. We thought the independent energy provider was a compelling idea.

Mirant was interesting because it had just a "B1" rating from Moody's (MCO), implying around a 25% chance of bankruptcy within five years. The company was trading below book value at a Uniform price-to-book (P/B) ratio of 0.8 times, like it was priced for bankruptcy.

The company's credit default swaps ("CDSs") were priced at more than 750 basis points (bps). A credit default swaps acts as insurance on the bond, with a larger basis points spread indicating larger risk, just like how higher-risk drivers have to pay higher car insurance payments.

However, our intrinsic CDS (iCDS) sat at 282 bps, pointing out that it was a much safer credit risk. If Moody's would just reevaluate the company and its credit risk, bond holders and equity holders would be set up for big gains as the market stopped fearing bankruptcy.

But part of our theory on why equity investors could win big in the name was wrong.

The problem was that Moody's was never going to upgrade Mirant. Mirant was an independent energy provider ("IEP"), which the ratings agencies had decided was too high-risk of an industry. The IEP business model was at the whim of the spending and demand for regulated utilities and its customers, without any of the inherent stability of utilities.

There was a benefit for credit holders as they would be "overcompensated" for the risk of owning Mirant bonds. Even though bond holders would never see any capital appreciation, they would be paid roughly 5% more per year in interest than the fair-value of the company.

On the other hand, equity holders would never see a relief rally in the stock from reduced concerns about Mirant going bankrupt, because credit markets and rating agencies would never flash the "all clear" we were waiting for.

Another industry which rating agencies have historically disliked is the semiconductor industry and its equipment providers. Semiconductor production is viewed as too cyclical and competitive an industry, leading agencies to label them as high risk.

Because of this, Amkor (AMKR), a testing and packaging provider for the industry, currently sits at a "Ba3" rating. This is partially due to the company appearing to have weak cash flow from operations to service its debt.

However, GAAP accounting completely misrepresents the company's real performance with cash flows. By looking at Amkor's cash flows against its yearly obligations in the Uniform Accounting framework, Amkor is a much safer bet.

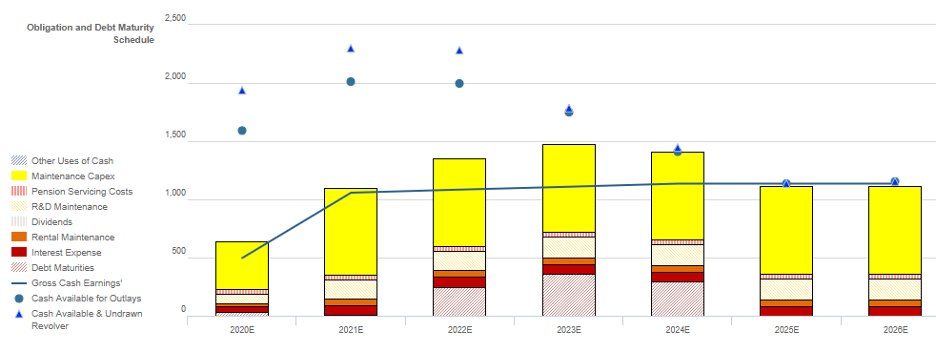

We can see this by looking at the company's Credit Cash Flow Prime ("CCFP").

The chart below explains Amkor's credit risk. The chart compares Amkor's obligations (stacked bars) each year for the next seven years against its cash flow (blue line) and cash flow plus cash on hand at the beginning of each period (blue dots).

The bottom bars are the ones that are hardest for the company to delay – things like debt maturities and interest expense. The higher bars are obligations that are more discretionary like maintenance capex and share buybacks.

The CCFP shows the company should have enough cash on hand to meet all its obligations through 2026.

Amkor also has a robust asset-based recovery rate on its debt of more than 100%, indicating easy access to the credit markets to refinance. Credit markets like asset-rich companies... not to mention Amkor has capex flexibility each year to free up further cash if necessary.

Additionally, Amkor has stable demand due to its utility-like nature. This will prevent huge declines in cash flow and make it more likely to be able to meet all its obligations.

Considering the unlikelihood that Amkor sees any operational pressure that could lead to bankruptcy, Amkor should not be a high-yield "Ba3" name. Rather, it should be an investment-grade "Baa3" name. That would also mean the bonds would trade at much tighter yields.

In the meantime, bond holders can be "overcompensated" for the risk of taking on this "risky" name, since the market is missing its strong cash flows, refinancing ability, and capex flexibility. Only when looking at the credit numbers through the lens of Uniform Accounting, does the company's safer credit profile become apparent.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

September 1, 2020

As the old joke goes, put two economists in a room and you'll get three opinions on the economy...

As the old joke goes, put two economists in a room and you'll get three opinions on the economy...