Imagine if apparel maker Hanesbrands still relied on the spinning jenny. Or if software giant IBM hadn't updated its servers since the 1980s.

We'd be paying more for scratchy underwear. And an IBM "desktop" computer would be a desk.

More likely, of course, Hanesbrands and IBM would simply disappear. Companies can't possibly compete without this one key factor.

You can find it on the balance sheet under the "Property, Plant, and Equipment" (PP&E) category.

Without investment in PP&E, manufacturing companies couldn't manufacture. Retail companies wouldn't be able to manage their inventory. And technology companies would be unable to design, produce, and distribute their products.

PP&E represents all long-term tangible assets a company uses to run its business, including office space, factories, production machinery, and vehicles.

All of these assets have a useful life before they become obsolete, break down, or need to be replaced. Companies depreciate the value of their PP&E to reflect the "aging" of their assets.

Most investors ignore PP&E when they buy a business. And often, they pay new prices for used quality.

You can get a sense for how old a company's assets are if you compare the value of a company's PP&E when they purchased it (gross value) to the current, post-depreciation amount (net value).

Looking at net/gross PP&E ratios over time tells us when companies need to spend more money to support their operations. Looking at this ratio for entire industries or countries can tell a story about larger investment trends.

At least, it should be able to. In reality, it takes some digging to figure out the real numbers, because GAAP numbers distort reality.

There are a lot of problems with the GAAP accounting for PP&E. These include issues around acquisitions, companies artificially writing down their assets, and bankruptcy-related accounting noise, to name a few.

As you know, we specialize in "Uniform Accounting" – a more reliable way of looking at companies than GAAP and IFRS accounting policies that distort the way we think about individual-company and macro factors like trends in investment.

Using Uniform Accounting, we remove the noise that GAAP creates. This lets us look at individual companies', and overall macro, capital expenditure ("capex") cycles, and gain better insights on how it can impact the market.

As companies begin growing their cash flows and see growth opportunities on the horizon, they have more incentive to invest in their PP&E.

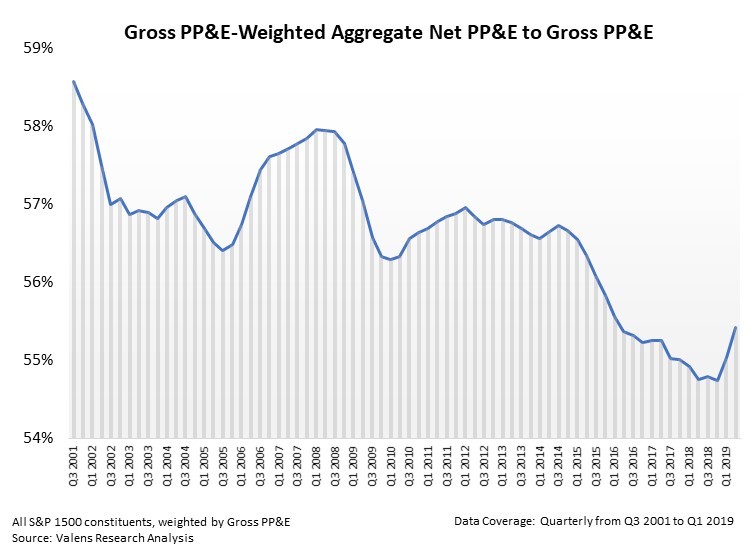

The chart below highlights the net/gross PP&E ratio for the S&P 1500 (1,500 of the largest public U.S. companies) since midway through 2001:

When this ratio rises dramatically – as it did beginning in 2005 – management teams around the country are aggressively investing in their assets to drive growth.

Rising investment generally leads revenue and earnings growth. This is a positive signal for upcoming economic growth and for the market.

Once the Great Recession began, management teams stopped investing. They wanted to conserve cash flows during a time of uncertainty.

After the recession, net/gross PP&E bottomed out at 56%. Then in 2010, companies began reinvesting to make up for lost productivity. Long-term net/gross PP&E across corporate America averages at 57% and higher. Companies tend to feel the pressure on their production when their ratio falls below this amount.

Companies continued investing until they reached 57% levels midway through 2013. Then, in 2015, as the energy crisis began to grow, many companies that were aggressively investing in capex, especially in the energy space, stopped investing.

Since then, companies across all sectors have limited further investment. And aggregate ratios hit multidecade lows in the first half of 2018.

At current levels, it is imperative that management teams begin allocating capital towards new investments. Any further declines in the age of their assets could lead to constraints on capacity and production levels. They could be Hanesbrands forced to use a spinning jenny.

Management teams appear to be realizing this need for capex. Since net/gross PP&E reached multidecade lows in the second quarter of 2018, we have begun to see an uptick in net investment, a possible signal that management teams have returned to a growth mindset.

This is an important lever to our overall macroeconomic outlook. Continued asset growth has three positive signals embedded within.

First, it confirms managements are anticipating future growth opportunities.

Second, it indicates that there are quality investment opportunities available for future growth.

Third, and most important, it signals that corporations are sufficiently profitable to support investment activity and management teams are not hoarding cash to prepare for economic turbulence. It means earnings growth is coming.

Strong earnings growth is what turns a positive market into a capital-letter BULL market.

That can't happen without strong investment trends. And now, we're starting to see those strong investment trends.

As they say, you need to spend money to make money.

Regards,

Joel Litman

September 6, 2019