It's as if airlines want to make you suffer.

The average coach seat is less than 17 inches wide. The average American man's shoulders are 16.1 inches across.

Still, it's hard to blame the airlines.

The business is hypercompetitive. It requires a huge amount of capital. Passengers will buy the ticket that's cheapest, with little brand loyalty. And every dollar and ounce counts.

American Airlines (AAL) saved $40,000 a year by removing a single olive in each meal. United Airlines (UAL) changed the paper stock on its magazines to cut weight. And a slew of previously "standard" offerings – from drinks, meals, and carry-on luggage – now come with a price tag.

The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 removed the federal government's control over fares and routes... and led to massive price wars between legacy carriers and new, low-cost startups.

That was a good thing for budget-focused passengers. But most startup airlines didn't last long. Between rising oil prices, aging airplane fleets, and a few snowy winters... the success rate in the airline business is slim.

We're reminded of the air industry proverb, often attributed to Virgin Atlantic founder Richard Branson:

What's the fastest way to become a millionaire?

Start with $1 billion and launch an airline.

In the 25 years following U.S. airline deregulation, 129 startups entered the industry. Of those, only 34 were still around by 2003. In the remaining group, it's increasingly becoming a race to the bottom, with competitors able to differentiate in fewer and fewer ways.

Delta Air Lines (DAL) is not exempt from these competitive pressures. The early 2000s were a tough time for airlines. Those who survived the Great Recession enjoyed a period of reduced competition.

However, the airline industry remains a cost-of-capital industry... meaning for every dollar an airline spends, it earns a dollar back.

And today, the market is missing DAL's comeuppance when it returns to historical norms.

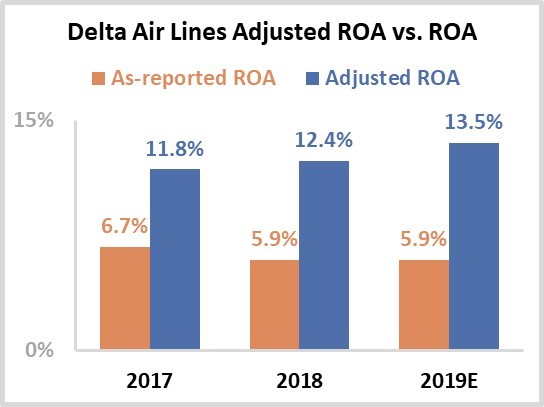

Delta looks like a cost-of-capital business through a traditional accounting lens, with a weak return on assets ("ROA") of 6%.

Armed with the knowledge that airlines struggle to generate profit in the long-term, most investors who focused on as-reported financial metrics likely expect that Delta's current profitability and valuation are sustainable.

Those investors are wrong...

Like many of the other airlines that survived the turbulence of the 2000s, Delta has actually performed quite well for nearly a decade – even if it isn't clear in the as-reported data.

As you know, we specialize in "Uniform Accounting" – a more reliable way of looking at companies than the GAAP and IFRS accounting policies.

When we apply our Uniform Accounting metrics, the distortions from as-reported accounting statements are removed – including operating lease capitalization versus expensing, treatment of goodwill, and acquisition distortions – and we can immediately see that Delta has seen its ROA improve significantly since 2009. It is currently two times stronger than the market realizes, at 12%.

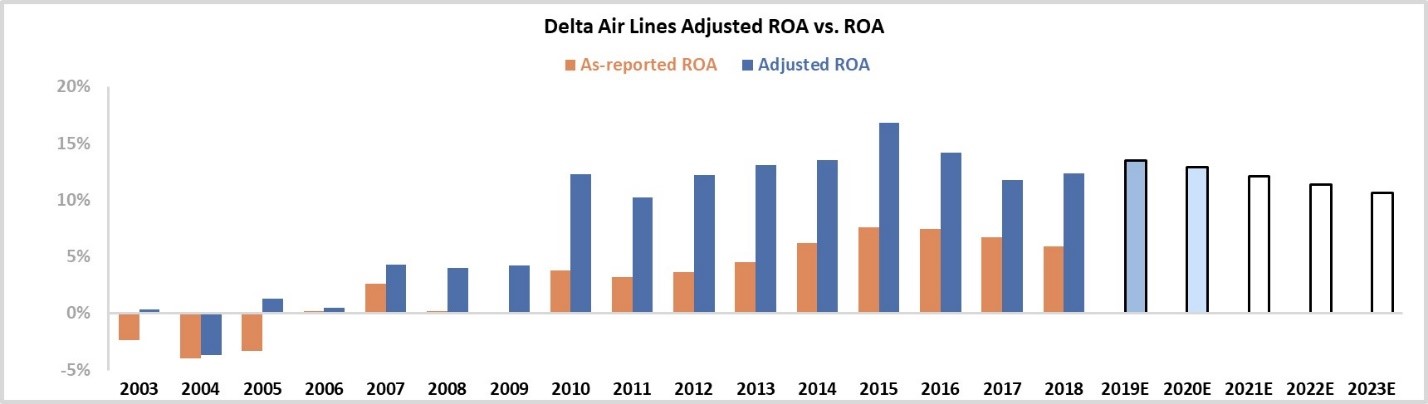

Similar to every other airline pre-recession, Delta saw weak returns that were consistently below its cost of capital. It even filed for bankruptcy in 2005 as fuel prices spiked and pension issues hung over the company.

But Delta was able to return from bankruptcy to take advantage of a wave of consolidation in the space during the recession.

It bought Northwest Airlines in 2008. The acquisition improved its scale. And it also improved Delta's competitive advantage by diversifying its routes and global presence. Delta also inherited a much more efficient internal operations and financial analysis framework, setting it up for better long-term planning.

As you can see in the above chart, by 2010, the merger proved its value. Uniform ROA exceeded cost-of-capital levels for the first time in the millennium. The relative lack of competition in the industry driven by a combination of bankruptcies and similar mergers poised Delta for a runway of successful years. This was amplified by recent declines in fuel prices, leading Delta to a historically strong year in 2015 and continued success through 2018.

But if we've learned anything from history, when there's an extra buck to be made in the airline business, newcomers are soon to join the market.

Through the first half of 2019, there are three outstanding certificated air-carrier applicants looking to begin operating in the U.S. And several other firms are in various stages of operation.

At current valuations, the market (white bars) is expecting Delta to see returns remain above the cost-of-capital. However, as competition increases in the long-term, Delta will be unable to maintain current levels of profitability. Furthermore, as ROA levels return to historical averages, Delta's valuations will follow suit.

Most investors cannot see this trend because traditional ROAs are already in line with historical averages. Investors think DAL is already at cost-of-capital levels, so there is less risk to returns and valuations in the long-term.

In reality, Delta is going to face increasing competitive pressures. Going forward, returns are likely to fade. And the market is not ready for it.

This is yet another example of why you can't rely on so-called standard accounting practices...

Regards,

Joel Litman

September 16, 2019