A continued eye on the coronavirus outbreak, from a data-driven perspective...

A continued eye on the coronavirus outbreak, from a data-driven perspective...

Financial-services firm Fidelity recently published a good piece summarizing the potential impact of the coronavirus outbreak on the markets and world economies.

In the analysis, Fidelity highlighted a few key datapoints that were similar to the ones we discussed in Wednesday's Altimetry Daily Authority:

- The 2003 SARS outbreak was a blow to Asian growth, but didn't disrupt the rest of the global economy... specifically in Europe and the U.S., where there weren't widespread outbreaks

- The economic impact of SARS on Chinese economic growth was brief – after one quarter of slowdown, the economy rebounded

- The market sell-off was a buying opportunity for investors due to the short-term nature of the outbreak

The article is a quick read... But much like our macro approach, it's focused on the data and comes back with sound responses to that data – as any good macro process should be.

The report comes to the same conclusion that we see... This is an opportunity to buy the dip, as the outbreak is unlikely to have any lasting effect on the global economy.

An inherent conflict of interest exists between aspects of medicine and finance...

An inherent conflict of interest exists between aspects of medicine and finance...

It's an undeniably noble cause to fight life-threatening conditions – this is the aim of many pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

Through extensive research, drug trials, and countless breakthroughs, we've been able to prevent, diminish, and cure some of the world's deadliest diseases and viruses.

For example, virologists Hilary Koprowski and Jonas Salk separately developed the polio vaccine in the 1950s. Over time, the disease has gone from a massive health concern to within a rounding error of extinct. In 1988, more than 350,000 cases of polio were reported. By 2018, that number was down to 33 globally.

While this is great progress, it's not done just for goodwill. Drugmakers and biotech companies are still businesses, and they need funding to continue doing good work. While early stage research is often funded by grants, this will only take the process so far.

Once a treatment or cure is created, it needs to be sold to keep the system viable.

This is at the expense of patients in need, with assistance sometimes provided by the government or by insurance companies.

In the news recently, we've seen plenty of discussions about price gouging for life-saving treatments.

For instance, EpiPen, the autoinjector used to prevent patients from going into allergy-induced anaphylaxis, reached costs upwards of $600 for a two-pack. The pens have a finite shelf-life, too, meaning that they're not necessarily good for two allergic reactions.

Another major example in recent years was Daraprim, the drug used to help fight AIDS. Its price rose from $13.50 to $750 per pill when the patent expired and was bought out by Martin Shkreli and his firm Turing Pharmaceuticals.

These seem like blatant cases where the pharmaceutical company was looking to maximize profit, but a middle ground is possible...

In fact, one company not only focuses heavily on developing HIV drugs, but it has also been hard at work trying to create a cure for the coronavirus.

We're talking about Gilead Sciences (GILD).

The company started with a sole focus on transforming HIV from a deadly virus to a manageable condition, and it has come a long way since then. Today, Gilead is worth nearly $100 billion and has countless drugs under development. It has been able to grow its drug pipeline both organically and through a number of smart acquisitions.

These acquisitions began back in 2011 when Gilead bought Pharmasset for $11 billion. At the time, Pharmasset was among the biggest players in hepatitis research... and this quickly became a staple of Gilead's core business.

This was a transformational acquisition for Gilead, but it wasn't the end of the road. In 2017, the company acquired Kite Pharma with a similar goal – to develop drugs to eliminate cancer.

Both acquisitions have been good from a research perspective... but it's less clear if they've been successful financially.

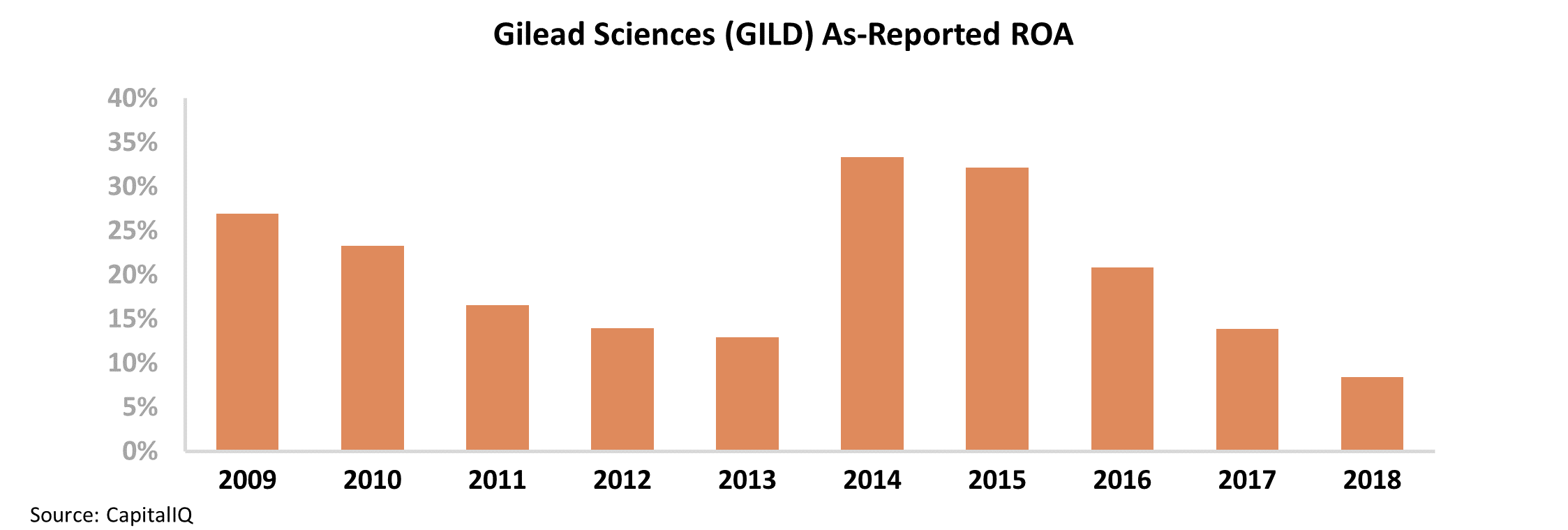

Since just prior to the Pharmasset acquisition, Gilead's as-reported return on assets ("ROA") has been somewhat volatile. After falling from 27% in 2009 to 13% in 2014, the company's ROA improved back to 33%... but has since fallen to a low of 8% in 2018.

Furthermore, after several years of declining profitability, it looks like investors expect this trend to continue.

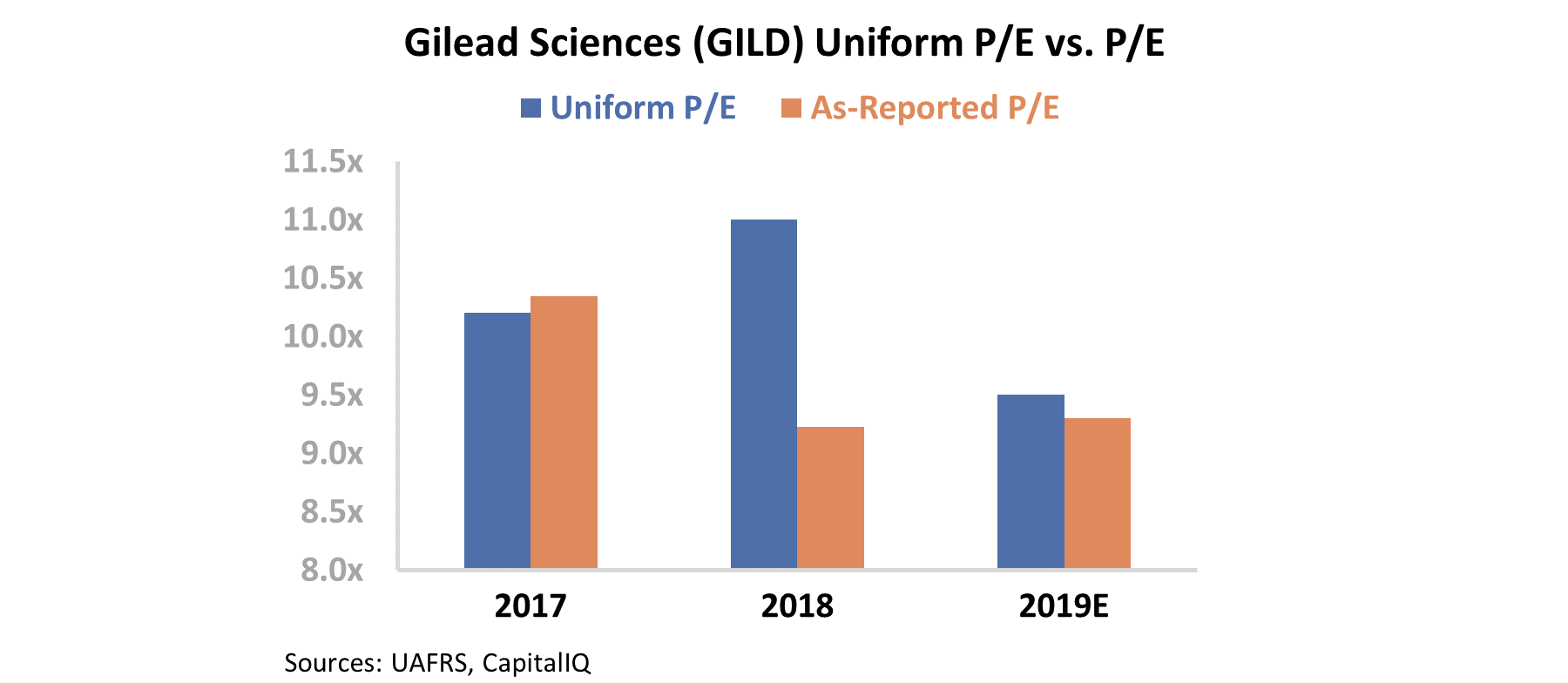

At current stock prices, the market values Gilead well below corporate averages when looking at the price to earnings (P/E) ratio. With averages near 20 times, Gilead currently trades for an as-reported P/E ratio around 10.

However, once we clean up the as-reported numbers, we can see that these profitability expectations may be too low...

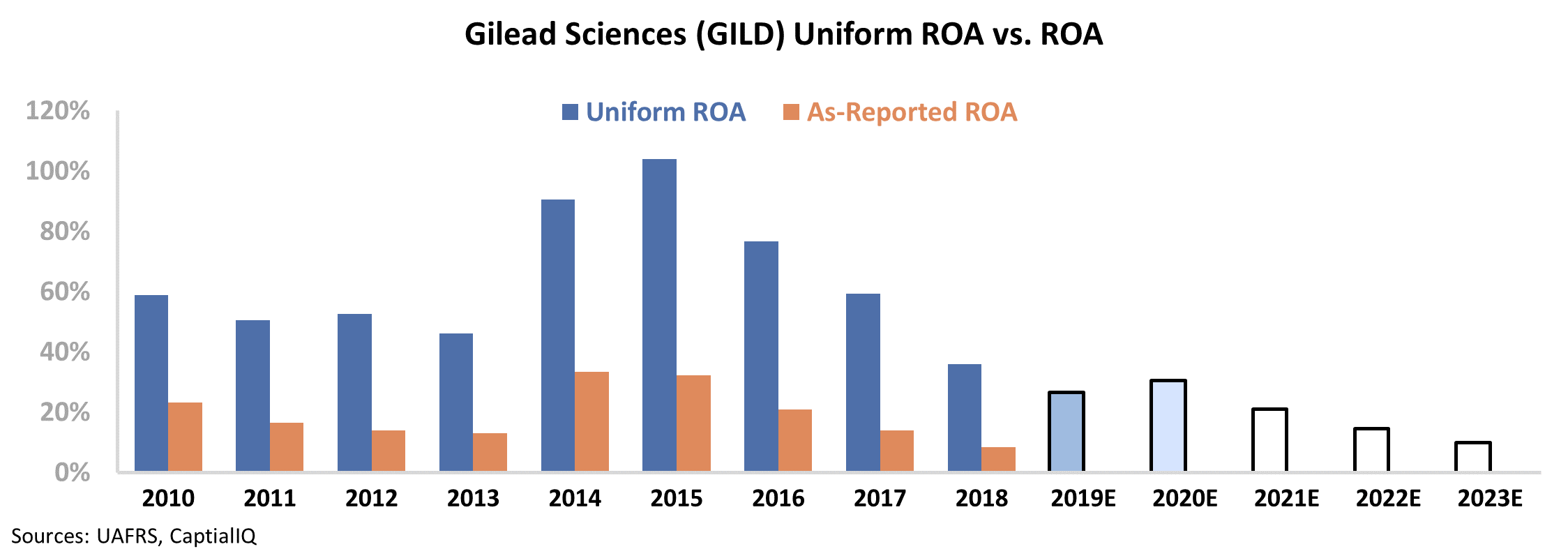

When we look at Uniform Accounting metrics, it's clear that misleading accounting items like the treatment of excess cash, goodwill, and research and development (R&D) expense have distorted Gilead's actual returns.

After making adjustments for these distortions, we can see that the company's ROA is far stronger than as-reported metrics highlight... and that the market likely has the wrong expectations.

While Gilead's Uniform ROA has fallen in each year since 2016, it's still projected at 27% in 2019 – three times higher than corporate-average levels. Furthermore, expectations are for the company's ROA to fall by more than half over the next five years to levels Gilead has never seen before.

Despite recent trends, this appears overly bearish. And considering that Gilead has yet to complete all of its cancer research, this could open a massive opportunity for the company. Gilead's progress with a coronavirus treatment could also benefit the company's bottom line... along with saving lives.

As Gilead continues focusing its resources on developing these groundbreaking treatments, we can expect positive results for both patients and investors.

Regards,

Joel Litman

February 28, 2020

A continued eye on the coronavirus outbreak, from a data-driven perspective...

A continued eye on the coronavirus outbreak, from a data-driven perspective...