No industry has fully avoided adapting to the pandemic...

No industry has fully avoided adapting to the pandemic...

Even the traditionally boring trucking industry has been disrupted. Many of these carriers saw business crater during the initial shutdown. However, demand bounced back due to a surge in online orders, which overloaded logistics organizations.

In the trucking industry, "last-mile transportation" has changed the most during the pandemic. Traditionally, larger operators deliver goods to warehouses where last-mile delivery services finish the actual deliveries.

The pandemic has caused increased volumes of small package deliveries, and these traditional carriers have become a bottleneck. This has created an opportunity for trucking companies to expand their business.

Large trucking and fleet operators have had to adjust to the increased focus on last-mile delivery. This includes online groceries, small packages, and goods people are buying to improve their living space during the "At-Home Revolution."

All of this has meant a huge spike in demand for local drivers over the past few months.

Pizza chain Papa John's (PZZA) has already hired more than 14,000 new delivery drivers this year alone and plans to hire 6,000 more by the end of the year.

Many other companies that saw increased demand were forced to adjust their private fleet operations. Brakebush Brothers, one of the largest providers of processed poultry, acted quickly to address increased last-mile demand. The company saw record sales volume in June as customers became more accustomed to ordering online.

There is significant opportunity here... and transportation companies that don't adapt to the increased demand for last-mile delivery may face obsolescence.

Ryder (R) is one of these companies seeing a shift in its industry...

Ryder (R) is one of these companies seeing a shift in its industry...

Ryder provides transportation and supply chain solutions to customers worldwide. Ryder leases its fleets of trucks and provides dedicated drivers and trucks to service customer needs.

Ryder has adapted to the At-Home Revolution by continuing to develop its last-mile delivery services, which it started in 2018, when it expanded its Ryder Last Mile segment in 11 North American markets. This solution is focused on getting Ryder closer to the consumer.

The company's e-fulfillment network now encompasses more than 135 facilities covering nearly 95% of the U.S. and Canada, making Ryder the second-largest last-mile provider of big and bulky goods.

The firm has adapted to an increased demand for small goods as a result of the pandemic. It has shifted its focus from bulky products to these smaller deliveries. Expansion into more major metro areas is a huge opportunity for Ryder to grow the business beyond traditional channels.

This means Ryder must increase its capital expenditure ("capex") spending to meet the shifting demand. Capex refers to investments into the physical assets of a company. For Ryder, these are investments in more distribution centers and the expansion of fleets to meet last-mile demand.

However, Ryder will likely have limited flexibility in managing or limiting capex in the near term. It needs to keep up with shifting demand toward last-mile delivery to stay competitive.

This capex spend is an issue which creditors appear to be ignoring completely. When we look at Ryder's Credit Cash Flow Prime ("CCFP"), we can see the limited flexibility and increased credit risk of the firm.

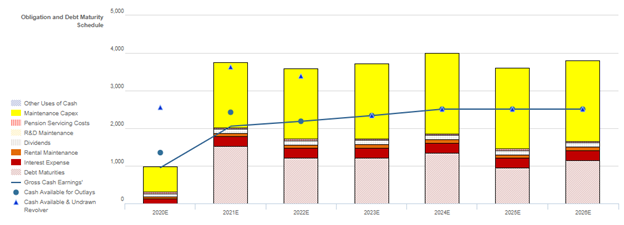

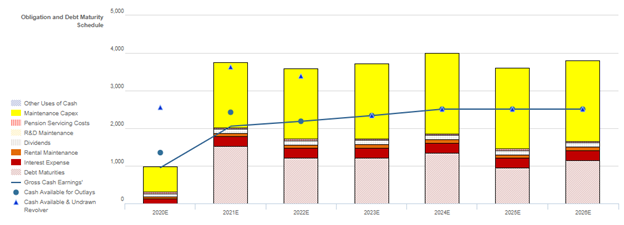

The chart below explains Ryder's credit risk. The chart compares the company's obligations (stacked bars) over each of the next seven years against its cash flow (blue line) and cash flow plus cash on hand at the beginning of each period (blue dots).

The bottom bars are the ones that are hardest for the company to "push off," with costs such as debt maturities and interest expense. The higher bars are obligations that are more discretionary like maintenance capex and share buybacks.

As the CCFP highlights, Ryder has consistent debt maturities every single year and it will need to refinance to avoid bankruptcy.

Typically, companies cut capex spending to generate additional cash to pay off these maturities if it can't refinance them. However, with the shifting competitive landscape, Ryder needs to continue to invest in improving its last-mile delivery.

If Ryder can't reduce capex, it's at the whim of the credit markets. This ultimately increases Ryder's credit risk, as it's increasingly reliant on factors out of its control.

Ryder's cash on hand, including revolver capacity, will fall short of meeting obligations in every year forward, starting in 2021.

The company is in the unique and unfortunate spot of needing to make these capex investments to keep up with the shifting competitive landscape, or risk being left behind.

This makes Ryder a much less attractive credit option than the ratings agencies realize... Ratings agencies love rental businesses, and Ryder has a "Baa2" investment-grade credit rating, which implies little credit risk.

The reality is Ryder's limited capex flexibility and material debt headwalls make this a much riskier firm. Valens Research, the firm that powers Altimetry, rates it as a HY2, equivalent to a B2 Moody's rating, or six notches below where Moody's currently rates the credit. This takes it from an investment-grade name to a "junk" name.

Ryder may look like an attractive credit option using only the ratings agencies' scores. However, when looking at the firm from a Uniform Accounting perspective, the real risk becomes clear.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

September 29, 2020

No industry has fully avoided adapting to the pandemic...

No industry has fully avoided adapting to the pandemic...