Dear reader,

In the early 18th century, the ruler of Japan was in trouble... all due to the price of rice.

In feudal Japan, rice was the most important source of food for farmers. Due to its value, it was paid to local nobles known as "daimyo" as a tax. As these lords then paid their soldiers in rice, the grain became the de facto currency for the country.

However, a series of poor harvests in the late 17th century and exceptionally good harvests in the early 18th caused the price of rice to swing wildly. Sensing an opportunity to make money, the nascent merchant class of Japan came together at Dōjima to change financial history.

Off the coast of Osaka, rice merchants began to speculate on the price of the grain, using paper slips that represented the next year's harvest. They had created the first modern organized futures market... locking in current prices for future production.

The ruler of Japan – the shogun – disapproved of these activities, as the daimyo were afraid that speculation would cause the price of rice to become too expensive for the peasants to buy.

Riots soon developed throughout Japan, as speculators stockpiled and flooded the market with rice in order to profit off their trades. Dōjima became a financial nexus... and elaborate smoke signals, carrier pigeons, and flag systems were developed to communicate the price of rice across the country.

After failing to ban the illicit futures market, the government decided that if it couldn't beat the merchants, it would join them... In 1773, it absorbed the market.

The rice futures market became a crude form of monetary policy, as the government issued paper notes that were backed up by the price of rice. The Dōjima merchants slowly transitioned into bankers, holding vast sums of rice and making loans to the daimyo.

Jump to the 19th century... and the Chicago Board of Trade in the U.S. was formed as the first exchange to standardize forward contracts, also known as "futures contracts." In 2007, the organization merged with the rival Chicago Mercantile Exchange – the first publicly traded exchange in the U.S. – to form CME Group (CME).

One of the members of the UAFRS council – the group that helps us identify the adjustments that need to be made to distorted as-reported accounting – is Jack Sandler. He was a member of the team that took the Chicago Mercantile Exchange public on December 6, 2002. He also played a significant role in the acquisitions of the Chicago Board of Trade in 2007 and the New York Mercantile Exchange in 2008.

After taking the company public and rolling up competitors, CME Group has become the largest futures exchange in the world. The company has expanded rapidly, through offering larger and more varied products – including credit default swaps ("CDSs"). These function as insurance on an underlying bond. By writing a CDS, an investor can speculate on the credit worthiness of a company, by ensuring the buyer repayment in the event of a default.

After the financial crisis, there was a huge push to move over-the-counter financial products onto an exchange, as this would mitigate the risk of these synthetic investments.... And CME Group got in front of this trend.

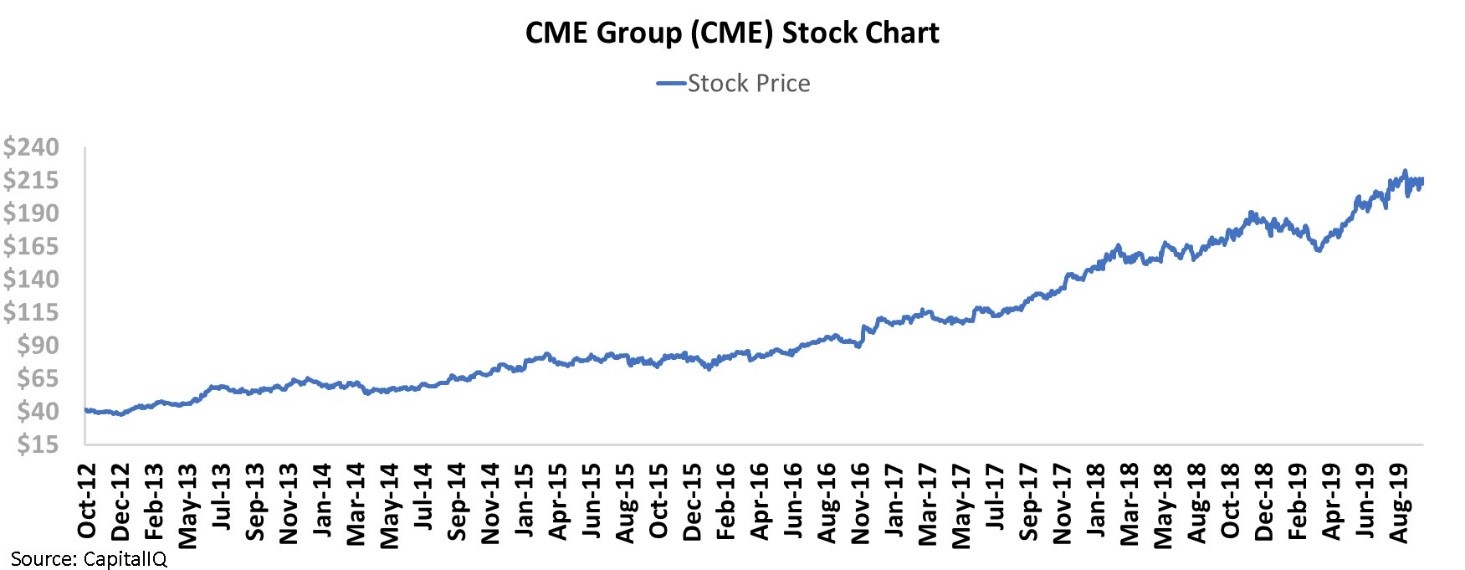

The market has rewarded the company's diversification and growth. As you can see, CME shares have been in a steady uptrend in recent years...

However, all is not what it seems...

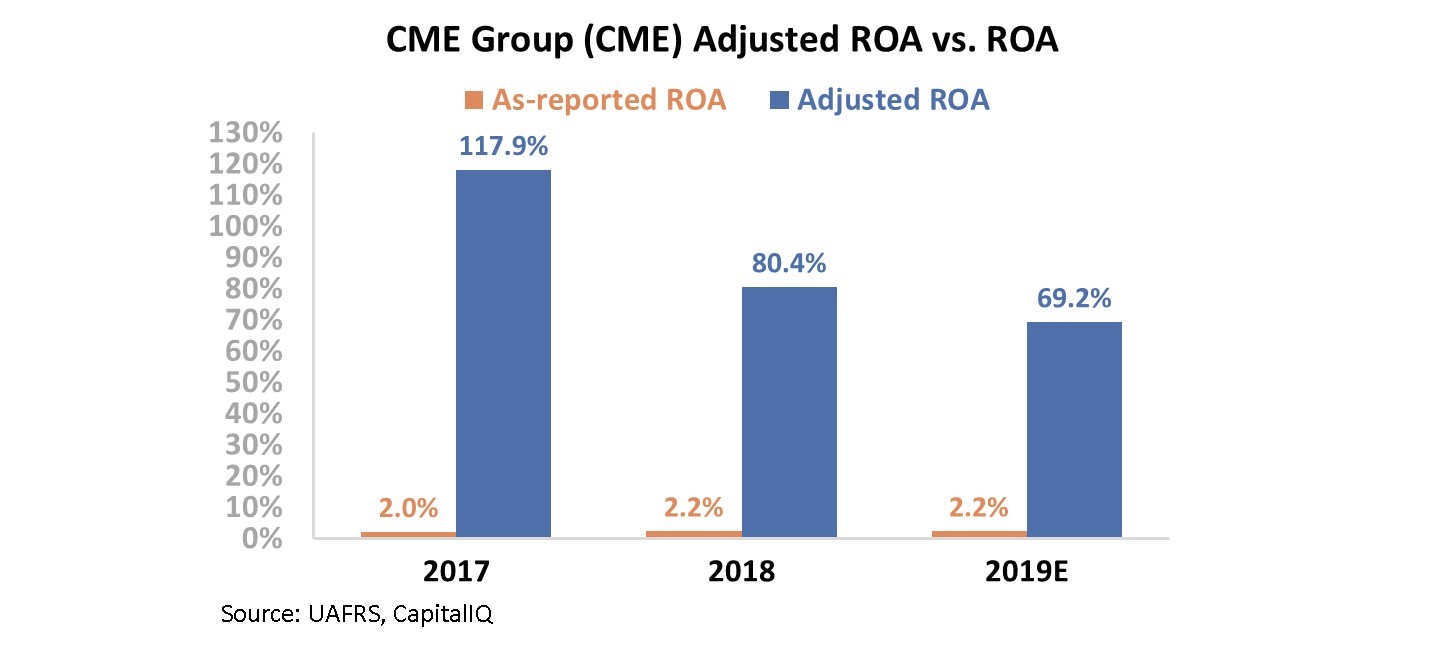

Due to the incorrect treatment of goodwill – and other distortions from as-reported accounting metrics – CME Group has seen its return on assets ("ROA") understated significantly. In 2018, the company's as-reported ROA was 2%, 40 times lower than its true Uniform ROA of 80%. However, not only has GAAP accounting failed to capture the magnitude of CME Group's ROA... it has also missed the trend lower. Take a look...

While as-reported metrics have shown small increases in ROA, Uniform Accounting reveals that the growth streak for CME Group is long over. The company's Uniform ROA has fallen significantly since 2017, with a further decline predicted for 2019.

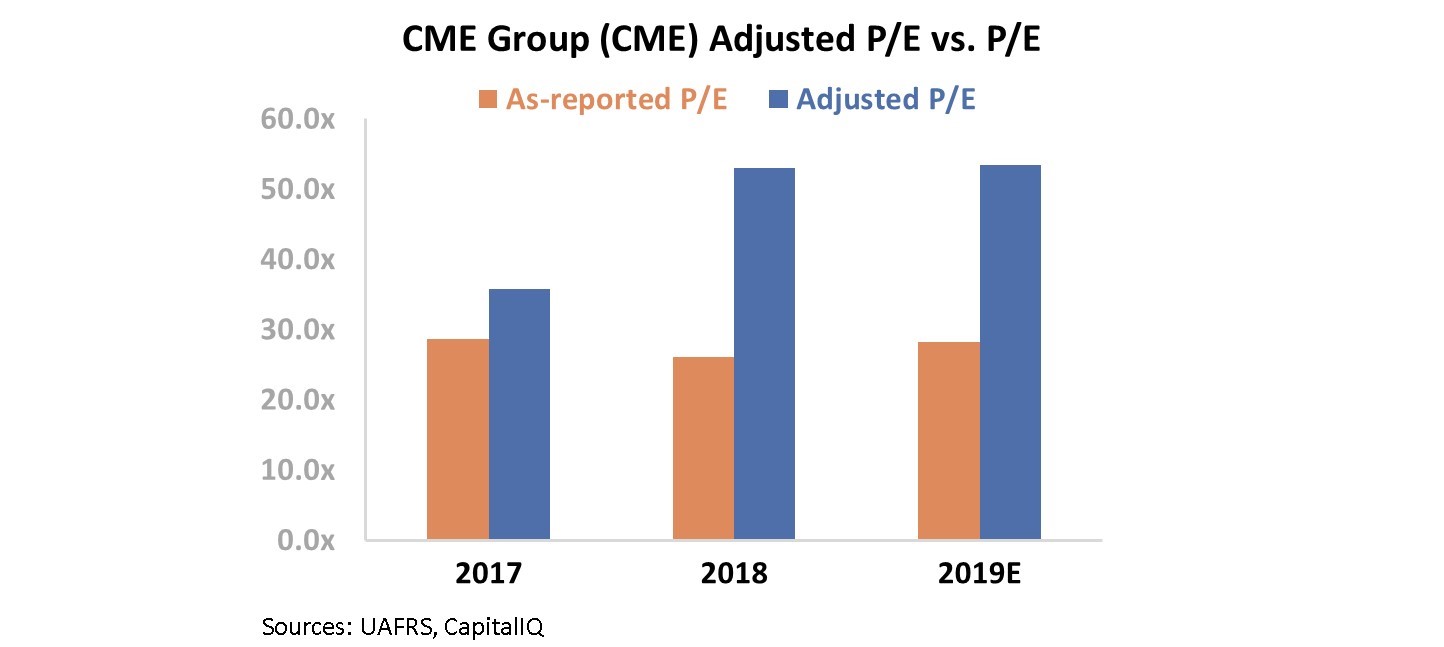

However, the market is still trading under the false premise of improving returns. Under as-reported metrics, CME Group trades at a slight premium, with a price-to-earnings ("P/E") ratio of 28.2. While this might be justified for a business that has been continuing to drive growth, CME Group actually has a Uniform P/E ratio of 53.4... more than 250% above market averages.

Not only has the company failed to grow over the past two years, but it is are priced higher than investors realize. Without the benefit of Uniform Accounting, the market is continuing to buy into a trend that is long gone.

Regards,

Joel Litman

November 1, 2019