Asset-management firm Blackstone's (BX) $150 billion in 'dry powder' sounds like a big deal, but how this can be used is another story...

Asset-management firm Blackstone's (BX) $150 billion in 'dry powder' sounds like a big deal, but how this can be used is another story...

Last week, CEO Steve Schwarzman discussed in an interview with Bloomberg how Blackstone has $150 billion in cash to look for potential private-equity ("PE") and real estate targets in this dislocated market.

That sounds like a powerful number, but don't get too excited...

The reality is that – as a report from Pitchbook on first-quarter PE performance highlights (you just have to register to get access, but the report is free) – while deal-making activity in the quarter was above the levels in the same period last year, this was due to holdover deals before the coronavirus pandemic struck. Later on in the quarter, the number of deals dried up significantly.

Banks had been "on the hook" for the financing they had to give for deals that were already agreed upon before the coronavirus pandemic struck. And as those deals closed, banks were still legally obliged to step up and fund them.

But now, two things are likely to reduce Blackstone's real ability to unlock that $150 billion in cash...

First, those banks are unlikely to be as willing to give Blackstone deal financing as easily as they did last year. This will make taking advantage of these opportunities more challenging.

Just as important, the idea of a $150 billion pile of dry powder is a bit of a misnomer. Blackstone doesn't have that money sitting in its bank accounts waiting to deploy... It has to ask its limited partners ("LPs") – the investors in its funds – to contribute that capital when a deal comes up.

The reason that PE deals rarely occur in the midst of a recession isn't just because of banks' hesitation... it's the fact that it's bad business to ask LPs to finance deals when their assets are losing significant value.

So while Schwarzman may talk a lot about the opportunities for Blackstone, the reality is that PE isn't going to be the big winner in this market.

There are only two kinds PE deals...

There are only two kinds PE deals...

If you ask a PE investor what he does, he might give you a textbook answer. PE firms work to take companies private – they lever the business up to increase their return on equity so that they're able to make a sizable gain in a less liquid market.

However, what the PE investor doesn't like to talk about is how these firms actually buy. PE firms generally move in on a potential target for two reasons... and the first is to effectively "rent" the company.

Just like any other business, a PE firm is looking to take on a project with a return in mind. This is why for many PE deals, the firm looks to get in, transform the business in three to five years, and then sell – leaving the company worth more than what the firm paid.

Leveraged buyouts ("LBOs") saw a rise in prominence in the 1980s. Large firms emerged as the cost of credit dropped, so it was more affordable to accept significant debt to take companies private. Companies like asset-management firm KKR (KKR) believed they could acquire a business, turn it around, and sell it – thus making money on the "rental."

The second reason a PE firm generally buys a company is for a source of long-term income. These are high-quality companies with solid cash flows and steady returns. They can handle the massive leverage from the acquisition and keep building value. These companies are the same kind of businesses legendary investor Warren Buffett looks for, though he doesn't use as much leverage.

We can see a great example of this kind of deal with hospital giant HCA Healthcare (HCA)... The company has gone through three different LBOs over the past 40 years. After HCA Healthcare went through its most recent initial public offering ("IPO"), the founding Frist family and KKR maintained 20% of the ownership stake. Rather than "renting" the company, the insiders saw the long-term value and decided to continue to be owners.

Aerospace firm TransDigm (TDG) is a public company that operates like a PE buyer... and that second type of acquisition has become its standard operating procedure. Over the past 30 years, TransDigm has tactically taken on debt to purchase companies that it believes will unlock long-term value.

TransDigm "levers up" – taking on debt – in order to buy a company that has seen its product adopted in commercial or defense aircraft designs.

Once a product is designed into an aircraft, has passed safety tests, and receives regulatory signoff, it's unlikely that product will be replaced in the design. A replacement would need to go through similar rigorous reviews, which would take time.

This means the acquired companies' cash flows have incredibly high visibility.

Due to the long life of these businesses' products, TransDigm is able to turn off the research and development (R&D) costs and reap the benefits of the long product life, before levering up to acquire another company.

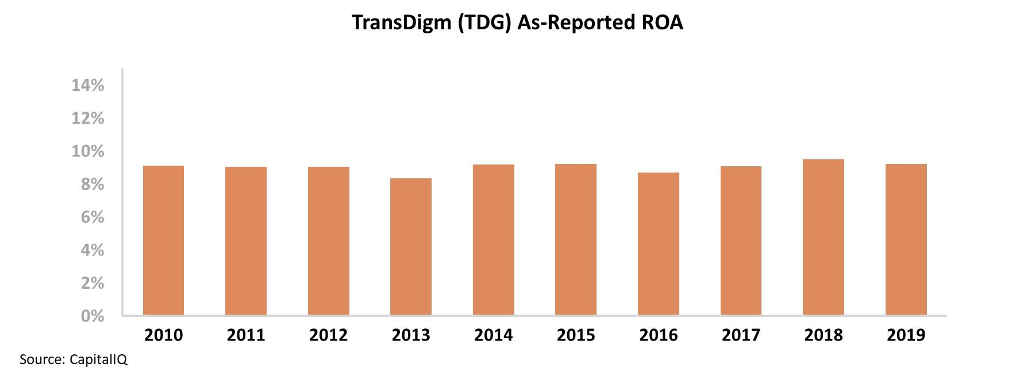

And yet, using GAAP accounting practices, it appears that TransDigm's strategy has little to show for it. Over the past 10 years, the company's as-reported return on assets ("ROA") has floated between 8% and 10%...

It would be easy for any analyst on Wall Street to write off TransDigm's strategy as a waste of time. Looking at the as-reported data, it's no wonder the market is spooked after TransDigm's newest acquisition – the $4 billion purchase of Esterline last year. Is TransDigm simply throwing away shareholder capital with a stagnant strategy?

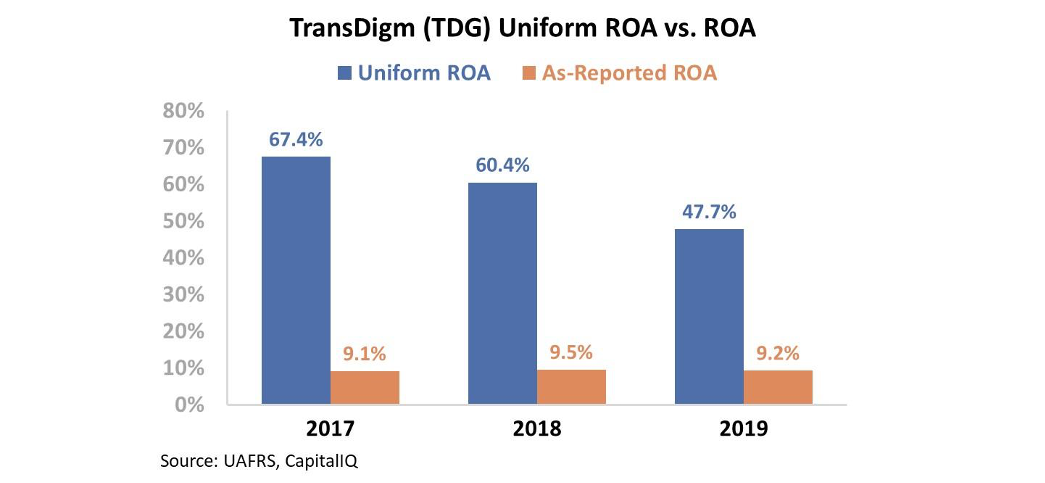

It's not... And in fact, as-reported accounting fails to capture the effectiveness of the strategy. After we adjust for goodwill, interest expense, and other distortions, we can see how successful TransDigm has really been.

As you can see in the chart below, rather than seeing ROA below 10%, TransDigm had an ROA above 60% in 2017 and 2018. In 2019, the company's ROA fell to 48% due to the integration costs of the Esterline purchase... but this was still massively higher than the as-reported 9% figure.

Because the market is using data that doesn't show the power of TransDigm's strategy, expectations for success must be muted. And by looking at embedded expectations, we can see exactly how muted they are...

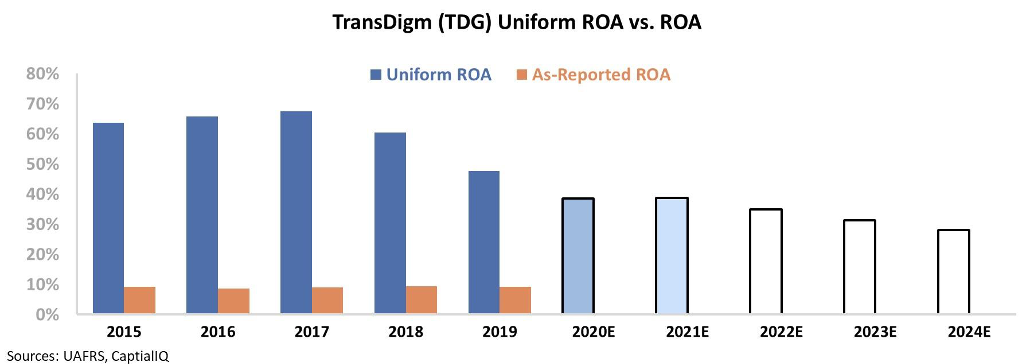

The chart below shows TransDigm's historical profitability based on Uniform ROA (dark blue bars) compared to analyst estimates for the next two years (light blue bars) and market expectations at current stock prices (white bars). Over the next five years, the market expects TransDigm's returns to fall to historical lows of 28%.

Cratering ROA is the worst-case scenario for TransDigm – one where Esterline continues to drag at performance through perpetuity.

However, if TransDigm is able to integrate Esterline – as it has done with countless other acquisitions over its history – and then unlock value with returns recovering, then significant upside potential is likely as the market catches on.

Regards,

Joel Litman

April 14, 2020

Asset-management firm Blackstone's (BX) $150 billion in 'dry powder' sounds like a big deal, but how this can be used is another story...

Asset-management firm Blackstone's (BX) $150 billion in 'dry powder' sounds like a big deal, but how this can be used is another story...