The 'gig economy' isn't just affecting folks' incomes...

The 'gig economy' isn't just affecting folks' incomes...

By now, we've all heard the conversation that started well before the coronavirus pandemic about the rights and quality of life for "gig economy" participants. But since the crisis, the risks these workers put themselves in and the changes in demand for these jobs – such as driving for ride-hailing service Uber (UBER) – have come into greater focus.

But until recently, a different part of the gig economy hasn't received as much attention... Many gig workers have to make real investments to be able to participate.

For instance, some people lease cars from Uber or buy cars outright for the opportunity to get riders.

Another company requires an even more significant investment from its participants: home-sharing service Airbnb. Some people subsidize their mortgage for a larger place than they'd be able to afford on their own by renting out rooms on the app, or subsidize a dream vacation home with expected short-term rental revenue.

Even riskier, some people have built small empires of condos or houses in popular destinations. They've been confident taking on the debt to buy these properties thanks to the cash flow they can generate on Airbnb... until now.

Unfortunately, one of the big draws for investors for the gig economy companies is that they don't have employees – they can have much more control over their cost lines and scalability, as well as reduced liabilities.

That's been a negative for the "contractors" who work under those companies, but the way these businesses are also shifting the risk of owning and maintaining assets to their partners is an underappreciated way the burden of risk in the gig economy is being shifted from the traditional employer to the employee.

Regulations for the gig economy are likely to continue to evolve and at some point come to the forefront again due to this crisis. This issue, which hasn't been significantly discussed before the pandemic, is likely to be at the front in the conversation.

Understanding cycles can be a powerful tool...

Understanding cycles can be a powerful tool...

As an investor, if you know where a company is within its business cycle, you can use that as another "buy" or "sell" signal.

For instance, sectors like Consumer Discretionary follow the economic cycle closely. If you had some way of predicting an economic slowdown, you could use that as a signal to sell any Consumer Discretionary investments.

Investors often talk about the automotive "replacement cycle" to predict demand for the car manufacturing industry and used car prices.

While the auto cycle is somewhat related to the economy, it's also affected by factors like technology advancements and urbanization trends... which makes the sector slightly tougher to accurately predict.

That said, even prior to the pandemic effectively shutting down the auto industry, it was widely accepted that the auto replacement cycle had already peaked and was starting to decline.

During the Great Recession, many analysts called for a massive transformation to the replacement cycle for office equipment, like computers, now that companies were learning to be more cost-sensitive.

Even still, the computer and office equipment replacement cycle is fairly quick – partly accelerated by technological innovation.

That said, some types of replacement cycles are far longer than cars or office equipment...

And one of these is the tractor replacement cycle.

Similar to automaker and consumer discretionary demand, the performance of tractor makers strongly tracks the tractor replacement cycle.

For context, the tractor replacement cycle is widely accepted to be roughly 15 years. While it isn't covered in the same way the auto cycle or our economy cycles are, we can draw a relationship between tractor maker demand and the replacement cycle.

And there's no better-known tractor maker than Deere (DE). The company manufactures the iconic John Deere brand of agricultural equipment. While it also makes a number of smaller mowers and construction equipment, its bread and butter is the tractor business.

Theoretically, Deere's profitability cycle should line up with the tractor replacement cycle.

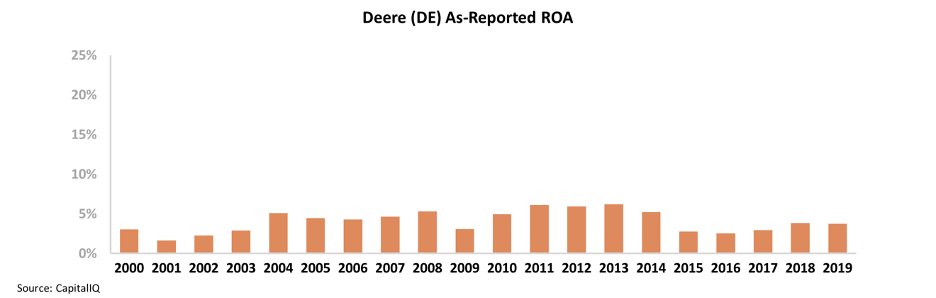

That said, looking at the company's as-reported return on assets ("ROA") over the past 20 years doesn't seem to reveal much about any cycle at all.

Since 2000, Deere's ROA has been fairly muted – mostly around or slightly below long-term corporate averages of 6%. If there's any pattern to its profitability, it actually looks more like Deere has gone through three or four cycles over the last 20 years. Take a look...

That doesn't line up with the expected 15-year tractor replacement cycle we discussed earlier... nor does it make Deere look like an attractive investment opportunity.

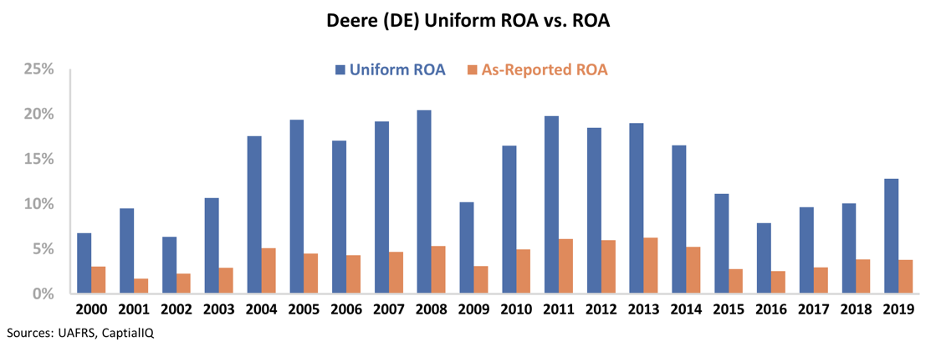

But when we look at the company's financial statements using Uniform Accounting, the connection becomes much clearer...

After adjusting for misleading distortions to as-reported financial statements – such as the effect of Deere's financial subsidiary (which is a completely different operating business), goodwill, and research and development (R&D) costs – we can see that Deere is a much more profitable company, and it might be just the right time to catch the next cycle.

On the Uniform Accounting view, it's clear that 2003 to 2008 was a booming period in the tractor business... which slowly faded to a low in 2016.

In 2009, most agricultural firms had to pause all expenditures... so that year is a bit of an outlier. When looking at Deere's profitability this way, it appears the tractor replacement cycle began in 2002, peaked just before the Great Recession, and faded to another trough in 2016.

It's no coincidence that 2002 to 2016 is exactly 15 years... nor is it a coincidence that Deere's ROA is starting to pick up again.

As the cycle repeats itself, that might mean significantly higher ROA for Deere again in the coming years.

It's easy to make sense of business cycles when looking at the Uniform data. Now could be the chance to buy Deere before its ROA expands back to cycle peaks, taking its stock price with it.

Regards,

Joel Litman

May 12, 2020

The 'gig economy' isn't just affecting folks' incomes...

The 'gig economy' isn't just affecting folks' incomes...