Dear reader,

Diseases can create companies and industries, and can just as easily destroy them.

Owens Corning, Armstrong World Industries, and other insulation companies went bankrupt in 2000 because of asbestos lawsuits from mesothelioma outbreaks. Gilead Sciences (GILD) is worth about $80 billion today from its drugs that treat HIV, hepatitis, and other liver diseases. An E. coli outbreak at Chipotle Mexican Grill (CMG) restaurants in late 2015 caused the company's shares to drop from more than $750 to less than $300.

And one disease – and trend – has been ravaging a part of the food industry that used to be core to America's mornings.

Celiac disease – an inability to process gluten – and dietary changes have taken their toll on the cereal industry as the disease has become more well-known.

We hear regular stories in the news about the benefits of a gluten-free diet. While only a subset of the people adopting a gluten-free or reduced-gluten diet have Celiac disease, the general shift has changed how consumers eat products containing gluten.

Caught on the wrong side of a market trend, cereal companies have come under pressure. Revenue in the segment declined from 2012 to 2016, falling from $15.7 billion to $14.2 billion. As cereal companies have looked to diversify into other breakfast foods, this trend has reversed for industry revenue as a whole, but cereal volumes in the U.S are barely up from 2016 levels.

In the cereal market, there are three large players, Kellogg (K), General Mills (GIS), and Post (POST). These businesses hold 30%, 30%, and 19% of the market, respectively.

With a challenged market for cereal, the CEOs of these companies have become more aggressive to preserve profitability. They have shrunk the amount of cereal in their boxes, have attempted to diversify their offerings, and have been consolidating the market through acquisitions.

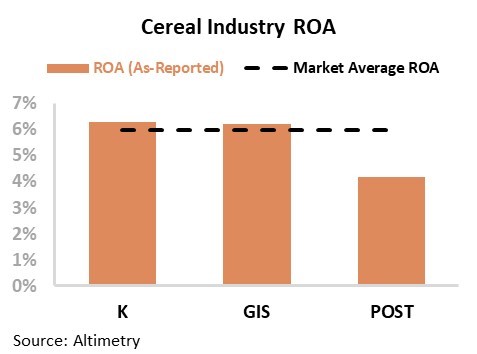

As Kellogg, General Mills, and Post jostle for market share, analysts fear these firms are eating away at each other's margins in this commodity business. And the numbers verify this concern... These companies have compressed return-on-asset ("ROA") values. In the chart below, you can see cereal makers' returns have been pressured to cost-of-capital levels. Post appears to be the worst of all, with a paltry 3.8% ROA.

To try to survive in a declining market, Post has been buying smaller brands to try to tread water. However, the company appears to be investing massively in a low-return business. This looks like a classic setup for a business that is destroying value through acquisitions.

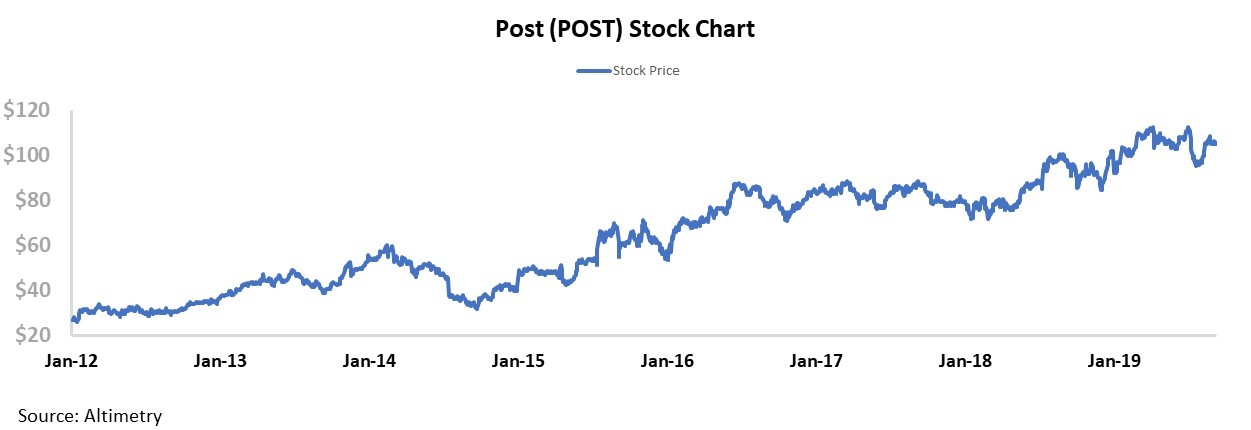

And yet the market has rewarded Post... Shares are up from $25 in early 2012 to about $100 today.

Investors are missing the story for Post, and it must be a screaming short... right?

As usual, it all comes back to the accounting. The as-reported numbers are so far from reality, they deceive the entire market to the current outlook of the entire industry.

Our Uniform Accounting metrics are a more reliable way of looking at companies than the GAAP and IFRS accounting policies. Numbers that distort the way we think about the impact of something are as important as industry fundamentals. How can we invest accurately if we can't understand top-down economics of the markets we invest in?

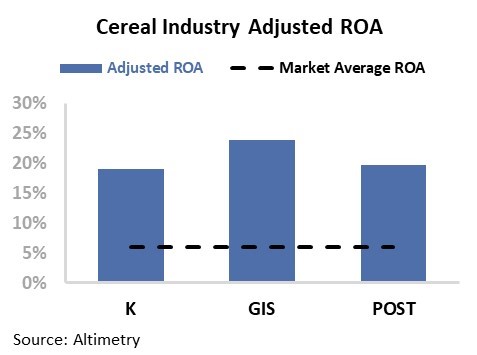

Instead of using the as-reported data, we provide the true returns which cut through the noise. Uniform Accounting tells a very different story...

The chart below highlights the ROA of each company after our adjustments are applied. Not only are Post's returns not below cost-of-capital levels... they are better than those of Kellogg's. The entire cereal industry generates a healthy, above-cost-of-capital return between 19% and 24%.

Post isn't a screaming short... In fact, the company is pursuing an intelligent strategy – consolidating a high-return industry – in the cereal and breakfast food space. Post is taking market share in a tactical way, and avoiding disruption from the gluten wave in a way the market is justifiably rewarding.

This is just another reason why as-reported accounting is misleading. By looking at only the GAAP numbers, investors can write off strong businesses from their portfolios. Through Uniform Accounting, we can look into a company like Post and understand the true face of the business.

Regards,

Joel Litman

October 8, 2019