Active investing has come under fire in recent years...

Active investing has come under fire in recent years...

Thanks to low fees and predictable performance, passive investing is all the rage right now. Active portfolio management is more expensive, so wealth managers, hedge funds, and mutual funds need to charge fees to operate. Even if the money manager's gross (pre-fee) returns beat the market – which isn't often the case – fees can erode any value added.

On the other hand, passive investing can recreate the returns of an index like the S&P 500 or Dow Jones Industrial Average for little to no additional cost. This means that many investors have poured money into passive mutual funds and exchange-traded funds ("ETFs").

However, this money is mostly going to a handful of firms. BlackRock (BLK), State Street (STT), and Vanguard dominate the space. In total, they have combined assets under management ("AUM") of roughly $17 trillion.

This means these firms have achieved massive economies of scale. Larger companies can save money by spreading IT, marketing, or other costs throughout the firm. Economies of scale are easy to realize for passively managed funds. There's no need for expensive money managers, only rebalancing when an ETF or mutual fund's underlying index changes.

Because these huge passive investment funds have such small fees, it can be hard for active managers to compete – especially smaller ones.

That is why hedge fund Trian Partners recently bought sizable stakes in two big active managers, Invesco (IVZ) and Janus Henderson (JHG). As The Economist explained last month, Trian wants to broker a deal between the two asset-management firms.

With a merger, Invesco and Janus could consolidate assets and reduce overhead. This may allow them to stay competitive with the likes of BlackRock.

For many of these firms, their survival may depend on consolidation.

But while the active asset-management sector may be suffering, one company has bucked the trend...

But while the active asset-management sector may be suffering, one company has bucked the trend...

One reason why Hamilton Lane (HLNE) has been successful is that it doesn't manage money.

Instead, Hamilton Lane acts as an investment solutions provider. It works with clients to conceive of, structure, and monitor portfolios. Hamilton Lane is also a "fund of funds" company – it invests in different investment funds instead of specific securities. This allows for broad diversification. Not only is it invested in different securities, it has exposure to different people and strategies.

Hamilton Lane's services give investors access to hedge funds they normally wouldn't be able to invest with. This exposure keeps investors coming back to the firm.

Over the past five years, Hamilton Lane's AUM has roughly doubled from $255 billion to $516 billion. This indicates how successful the company's strategy has been. Furthermore, as the company continues to grow, it can begin to leverage economies of scale and spread out its costs.

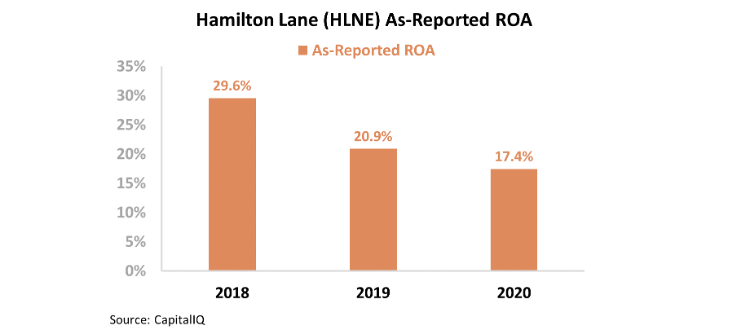

However, GAAP metrics tell a different story about how this is translating into profits. Hamilton Lane's profitability appears to have been declining over the past few years. The company's as-reported return on assets ("ROA") fell from 30% in 2018 to only 17% this year.

As-reported metrics may make investors wonder if they should take their money out of Hamilton Lane.

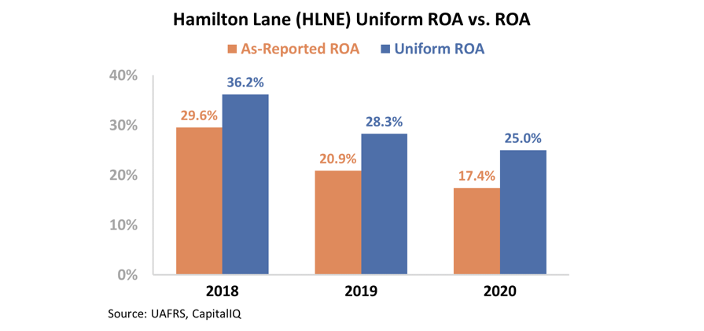

However, this is an inaccurate representation of the company's profitability. GAAP's treatment of minority interest and stock option expenses, among other distortions, are suppressing returns.

When we clean up the numbers through Uniform Accounting, we can see that Hamilton Lane's real ROA has ranged from 36% to 25% since 2018. While profitability is declining, it's doing so from a much higher level. Take a look...

Partly due to this distortion, the market has bearish expectations for Hamilton Lane...

Partly due to this distortion, the market has bearish expectations for Hamilton Lane...

To gain a greater understanding about what the market is pricing in, we can use our Embedded Expectations Framework.

Most investors determine stock valuations using a discounted cash flow ("DCF") model, which takes assumptions about the future and produces the "intrinsic value" of the stock.

However, here at Altimetry, we know models with garbage-in assumptions only come out as garbage. Therefore, we've turned the DCF model on its head with our Embedded Expectations Framework. Here, we use the current stock price to determine what returns the market expects.

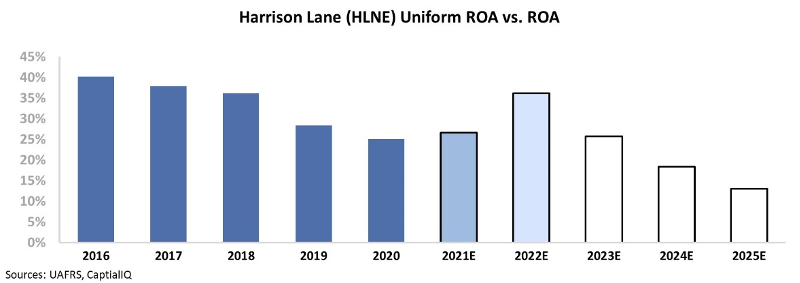

In the chart below, the dark blue bars represent Hamilton Lane's historical corporate performance levels in terms of ROA. The light blue bars are Wall Street analysts' expectations for the next two years. Finally, the white bars are the market's expectations for how the company's ROA will shift in the next five years.

Wall Street analysts are expecting Hamilton Lane's Uniform ROA to improve to 36% through 2022. They understand the firm's strong positioning in the investing space and the benefits it will realize from scaling.

Despite this forecasted growth, the market is pricing in Uniform ROA to collapse to 13% by 2025. This would be the lowest level for Hamilton Lane since it went public in 2017.

The market wrongly thinks that the company's ROA is already weak and expects it to keep falling from those weak levels. Expectations for a drop in ROA by roughly half in five years are way too pessimistic... but that's what investors are pricing in. Take a look...

Uniform Accounting demonstrates how successful Hamilton Lane has been in recent years. The company has grown its AUM and sustained a high level of profitability.

More important, it highlights how dramatically wrong investor expectations are for the company, clouded by as-reported metrics.

While the active-investment sector may be in decline, Hamilton Lane has stood out compared to the rest of the industry. If the company simply sustains current profitability levels, investors might want to keep its stock on their radar.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

November 17, 2020

Active investing has come under fire in recent years...

Active investing has come under fire in recent years...