It happens to everyone... and it can be frustrating.

It happens to everyone... and it can be frustrating.

When asked about something you know but can't remember the answer to, maybe you responded with something along the lines of, "I'll remember it later and let you know." But have you ever wondered why you tell someone that?

We have a saying here at the Altimetry offices when we're thinking about complex problems and an answer isn't immediately apparent... "Just 'Zeigarnik' it."

No, we're not throwing Russian words in our conversation... we're referencing the powerful Zeigarnik effect.

The term comes from a study by Russian psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik, after she and her professor noticed that a waiter at a restaurant had amazing recollection of what customers who had not yet paid had ordered. But he couldn't remember the orders of customers who had already paid.

The reason was that the waiter's task for the customers that hadn't paid wasn't yet completed. So his mind still felt it had to retain that information to make sure he could complete the task. Once the customers paid, the task was completed... and his mind cleared space for new tasks.

Here at Altimetry, we tell each other to "Zeigarnik" things because that same process works with other types of problem solving.

If you're trying to figure out the best way to solve a problem in a model you're working on or the best name for a new product, sometimes sitting and thinking about it is unproductive. Your mind gets caught in one path that can't be broken.

It may be better instead to step away from the task, and clear your head. As the Zeigarnik effect tells us, your subconscious mind will continue to work on the problem because it knows there's still a task at hand. The answer to your problem might come to you in its own time.

Our team can speak from experience... it works. The number of times we come up with creative answers to problems we run into when we're not thinking about them is amazing.

So the next time you feel like you're banging your head against a wall trying to solve a problem, stop. Instead, walk away from it and work on something else instead. The answer might come to you when you least expect it.

Investors paying close attention to market capitalization likely noticed an interesting milestone a few weeks ago...

Investors paying close attention to market capitalization likely noticed an interesting milestone a few weeks ago...

On January 16, Google's parent company Alphabet (GOOGL) became the fourth U.S. company to hit a market cap of $1 trillion. Just last week, Amazon (AMZN) also crossed the $1 trillion mark after it reported fourth-quarter 2019 earnings.

But the first company to ever reach this valuation wasn't iPhone maker Apple (AAPL)... or oil company Saudi Aramco. Instead, it was founded in 1602 by enterprising traders seeking to monopolize trade between Europe and Asia. At its peak, the Dutch East India Company reached a massive $8.2 trillion valuation in today's dollars.

All the Dutch East India Company's inheritors have carved a dominating presence in their markets – whether it's oil for Saudi Aramco, search engines for Google, or operating systems for tech giant Microsoft (MSFT). Despite the competitive advantages, concerns are often raised about the sustainability of these companies' incredibly high valuations.

Due to the rise of exchange-traded funds ("ETFs"), the next marginal buyer for these tech giants is the average investor. The benchmark S&P 500 is a value-weighted index, which means each company's position in the index is relative to its market cap. Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and social media company Facebook (FB) alone make up roughly 17.5% of the entire S&P 500.

This means that if your entire portfolio was dedicated to the S&P 500, you would be putting 5% of your money in Apple and 4.6% in Microsoft. And as more and more investors simply put their funds into ETFs, many people are concerned about buying these names because of the perceived risk that these trillion-dollar juggernauts are overbought bubbles.

The reason that the Dutch East India Company reached such high valuations was because of its trade in tulip bulbs, which subsequently helped cause the first true financial bubble in history. In 2007, when oil and gas firm PetroChina reached a valuation of $1.7 trillion in today's dollars, it was fueled by wild speculation... and since then, shares have lost more than $800 billion in market value.

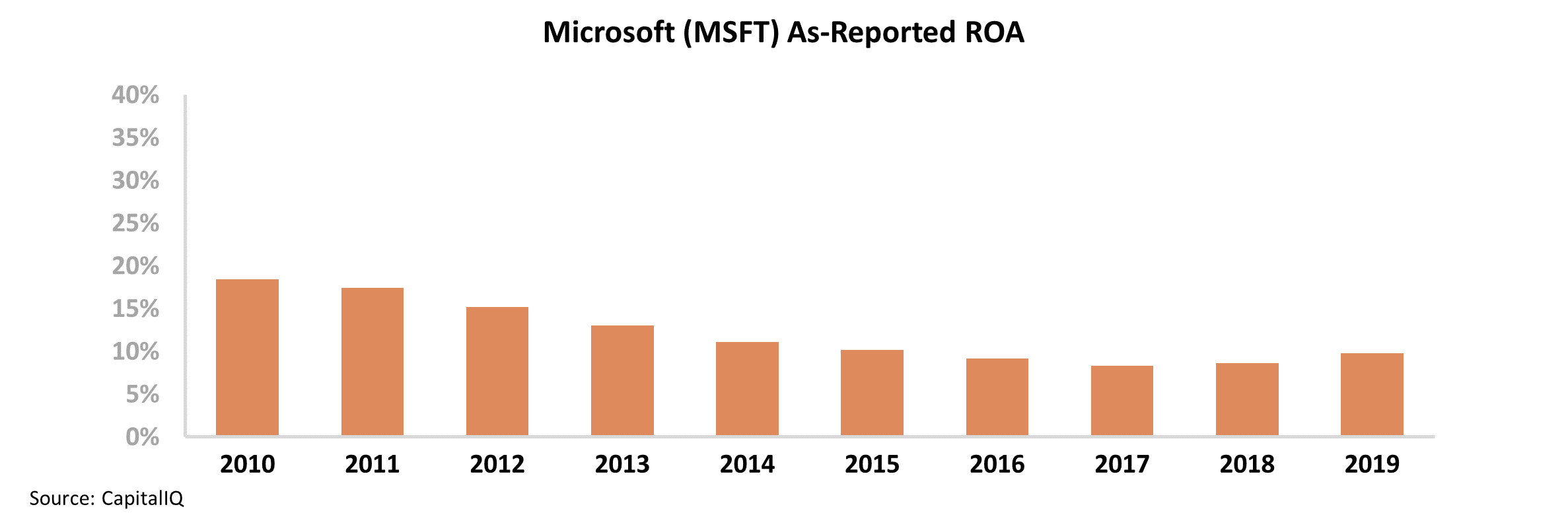

Looking at a company like Microsoft, it's no wonder that Wall Street has painted a similar conclusion for the aging operating system developer. Looking at Microsoft's as-reported return on assets ("ROA"), it appears that this figure has been trending steadily downward over the past 10 years – falling from 18% in 2010 to less than 10% last year.

Microsoft's as-reported price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio is even more troubling. The company's disappointing ROA is accompanied by a P/E ratio of 28.2 – almost 1.5 times market averages.

However, Wall Street's fears are built on the inherent distortions of GAAP accounting...

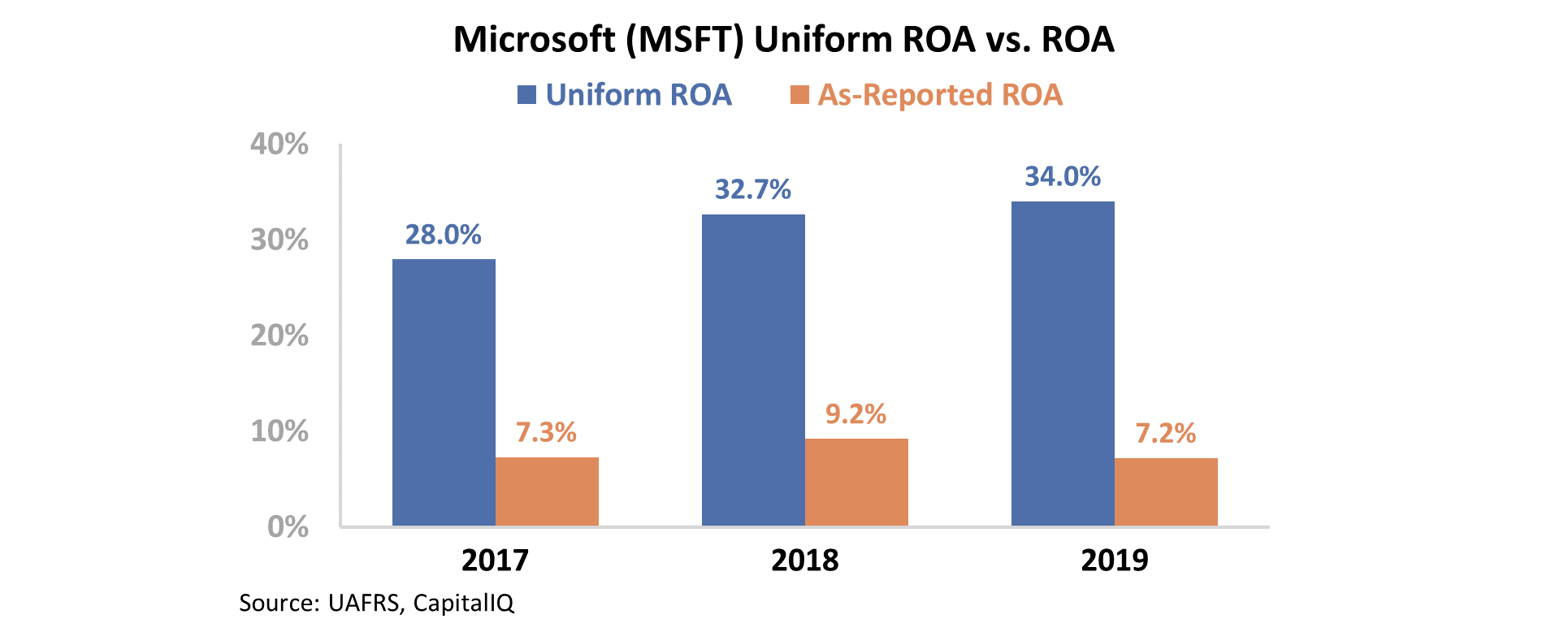

Over the past 10 years, Microsoft's returns have been pressured by as-reported accounting standards. Once we apply Uniform Accounting adjustments – namely around goodwill and excess cash – a significantly different picture emerges...

Rather than a P/E ratio of 28.2, Microsoft instead trades at a Uniform P/E ratio of 24.1 – much more in line with market averages. Furthermore, over the past three years, the company's Uniform ROA has improved steadily from 28% in 2017 to 34% last year. Take a look...

Over the past decade, Microsoft has been investing in alternative technologies such as cloud computing and virtual reality to stay ahead of the competition, which has driven improvements in its ROA.

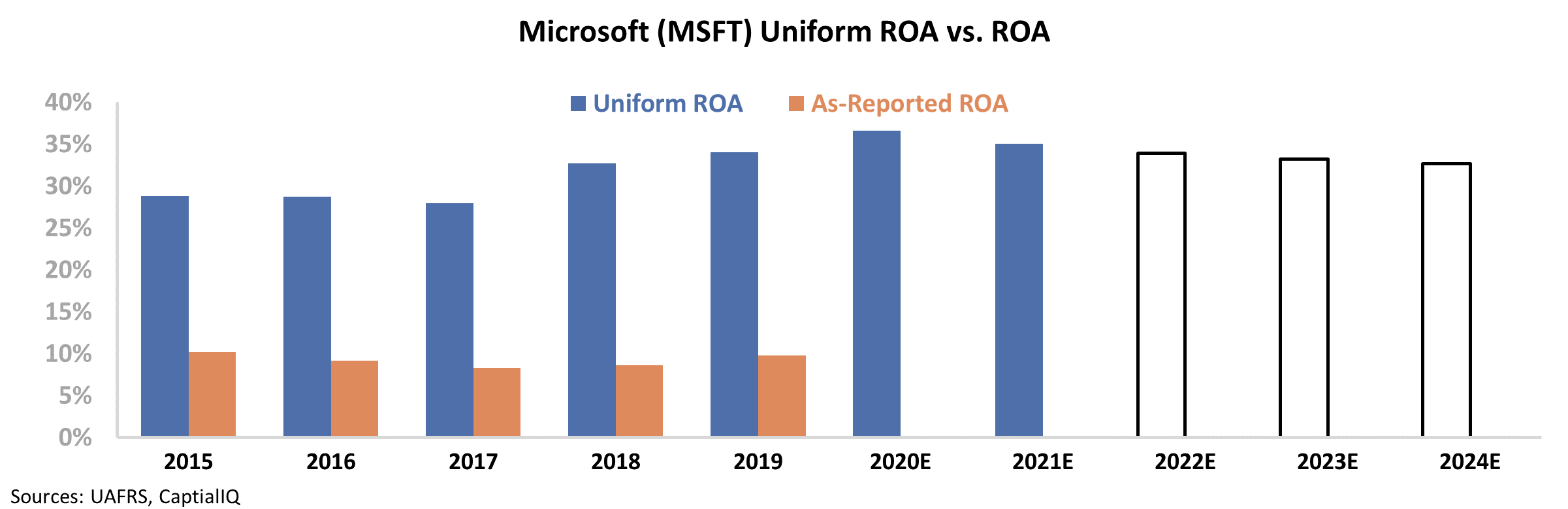

The power of UAFRS can also show market expectations to see if the company's current stock price is based on reality. The chart below highlights Microsoft's historical corporate performance in terms of ROA (dark blue bars) versus what sell-side analysts think the company is going to do for this year and next year (light blue bars) and what the market is pricing in at current valuations (white bars).

As you can see, the market has relatively muted expectations for Microsoft... anticipating that the company will sustain its ROA near 35%.

Sizable distortions in as-reported accounting have led analysts to believe Microsoft is an unsustainable bubble, rather than an adapting industry player. In reality, like the other $1 companies today, the tech giant deserves its lofty market capitalization.

Furthermore, if Microsoft continues to improve its profitability, even more upside ahead is possible.

Regards,

Joel Litman

February 5, 2020

It happens to everyone... and it can be frustrating.

It happens to everyone... and it can be frustrating.