According to Socrates, knowledge comes from asking questions, not stating opinions...

According to Socrates, knowledge comes from asking questions, not stating opinions...

In order to stimulate better thinking and understanding, the ancient Greek philosopher would invite his students – including Plato – to actively question the topics he discussed.

His "Socratic method" proved so powerful that today, thousands of years later, Socrates is still widely known... despite having never written anything down.

Think about that for a second... Socrates' dialogues alone led to his fame today – and those dialogues were full of questions.

But embracing the Socratic method isn't easy...

But embracing the Socratic method isn't easy...

We naturally want to jump to conclusions. We want to find answers and gain closure on open questions.

When I look back, some of my worst career and investment decisions were because I jumped to conclusions – and stopped asking questions – too soon.

Meanwhile, my best decisions came from delaying judgment. Resisting the need to have a fast answer forced me to ask more questions. In many cases, it led to asking different questions from new angles.

The Socratic method can be powerful for interpersonal relationships. Back when I was on Wall Street, I would often jump to conclusions about why I had disagreements with co-workers. I would make assumptions about their motivations that in hindsight turned out to be wrong.

It's easier to call someone out for making a mistake than it is to spend time questioning why mistakes happen. The obvious answer is often the wrong one... And the real answer isn't discovered because the questioning stops too soon.

The more people are emotionally invested in a topic, the more we need to find a way to put a suspension of judgement into the process. We need to stop and ask more questions.

The investment decision-making process can be exciting and emotionally charged. It's an incredible feeling to watch a stock that you bought go up 500%. Unfortunately, that excitement has to be tempered and judgment has to be delayed... or the investment ideas and process will suffer.

To implement the Socratic method in our investment processes, we often play devil's advocate during our analysis. We purposely make the case that the opposite of our investment thesis is true. We seek to continually question the thesis... and even if we're asking the right questions.

Far beyond investment processes, stopping to think and reform questions is a powerful tool for great working groups and better decision-making.

For that, we have to thank Socrates' students, who wrote down the philosophy and dialogues of their teacher. Ask more questions.

Half a decade ago, asking questions helped me temper my expectations when doing research for a big client...

Half a decade ago, asking questions helped me temper my expectations when doing research for a big client...

I was working with a client in Asia who had taken a major position in a big nickel miner.

The Indonesian government had announced it would ban nickel mining operations unless the miners processed the nickel within the country. The government wanted to stop the outright export of nickel and create a strong incentive for foreign companies to build their nickel processing plants in Indonesia.

In an example of the law of unintended consequences, not only did miners decide not to process in Indonesia, but they also sought nickel from alternatives to the country...

As a result, demand boomed for nickel from a company called Nickel Asia (NIKL.PM). Based in the Philippines, it was a reasonable geographic alternative to sourcing from nearby Indonesia.

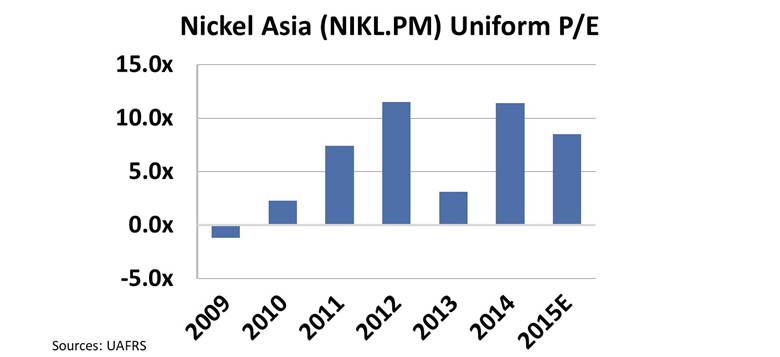

And yet, the company's Uniform price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio stood at a low 8.5 times. Take a look...

At those valuations, Nickel Asia looked like a screaming buy.

But sometimes, things are just too good to be true...

But sometimes, things are just too good to be true...

My team and I had already dug into the company's capital expenditure ("capex") budget for expanding nickel refining and looked at the expected demand for nickel over the next few years. It seemed promising.

For most, that would have been enough reason to like the stock, but we weren't done asking questions...

We needed to know why the company was trading for so cheap.

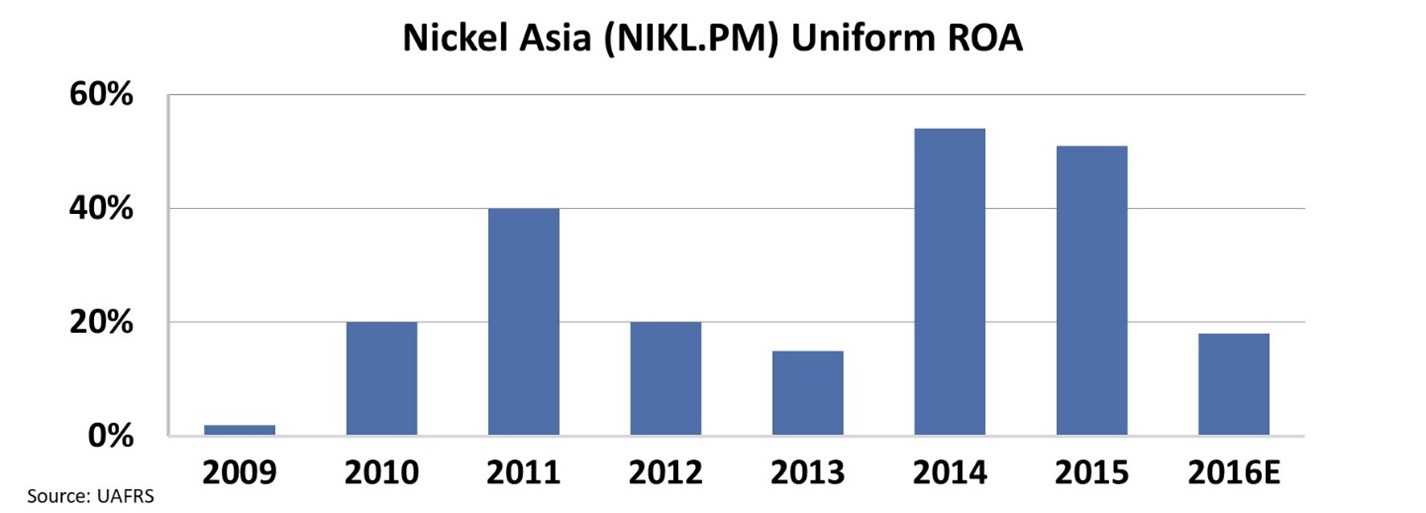

Delving deeper, we found that Nickel Asia's return on assets ("ROA") wasn't sustainable. The market was pricing in Indonesia to eventually open back up to miners. This would push Nickel Asia's high 54% ROA in 2015 back down to normal levels.

Low and behold, a year after our report, the stock had collapsed by 60%. Nickel Asia's Uniform ROA cratered to 14% in 2016.

The only reason we were able to identify what was going on is because we thought to ask, "Why is this stock valued so cheaply?"

Because we asked more questions, we were able to dodge a major bullet.

Here at Altimetry, we always work to incorporate this questioning and suspension of judgment into our investment analysis. Avoiding the easy answer leads to better decisions.

Regards,

Joel Litman

April 23, 2021

According to Socrates, knowledge comes from asking questions, not stating opinions...

According to Socrates, knowledge comes from asking questions, not stating opinions...