Historians and journalists peg 1946 as the 'official' beginning of the Baby Boom...

Historians and journalists peg 1946 as the 'official' beginning of the Baby Boom...

However, U.S. birth rates were already on the rise from 1941 to 1944, in the midst of World War II. This fact supports the research that wars don't necessarily create massive reductions in birth rates, as counterintuitive as that may be.

For that matter, blackouts – at least the ones in New York City in 1965, 1977, and 2003 – don't increase birth rates either. Many people assume that blackouts – an electrical version of a stay-at-home order – create a baby boom. The math says otherwise...

The fluctuations in birth rates that occurred nine months after the New York blackouts were within the normal range. During a blackout, people seem to think we'll do something more interesting than stare at each other in the dark... But whatever that is, it doesn't seem to affect population levels.

While neither wars nor blackouts significantly change birth rates, something else does: economic malaise.

The Great Depression, the Great Recession, and the downturn in the 1970s all contributed to statistically significant reductions in birth rates.

That means you can think of baby booms as the space between the "birth dearths." The periods of low birth rates affect the economy as much as birth booms.

I was born during the birth dearth of the early 1970s. My generation – and all of you currently in your late 40s and early 50s – was inside a much smaller age-based population group.

That meant lower aggregate spending ability... which translates into fewer revenue opportunities for companies to create video games, toys, or other things kids and teenagers do while they're growing up.

Similarly, some folks have argued that the decline in the housing market that led to the Great Recession could be driven by Baby Boomers wrapping up homebuying. My generation didn't have the same volume of need.

Being born during this dearth also meant I had fewer kids in my classroom than those several years younger or older than I.

And when I graduated college, it was easier to get a job since I had fewer graduating students to compete against. Compare that to millennials who have been graduating and finding far fewer jobs available.

It looks like we might be in a birth dearth now...

It looks like we might be in a birth dearth now...

When splitting up the population into five-year ranges, the zero-to-five cohort is by far the smallest of any group under age 65. Additionally, according to Forbes, it looks like the lockdowns due to the coronavirus pandemic aren't creating the mini baby boom some people have predicted.

As the crisis drags on, folks are concerned about health... and many are choosing to defer having babies.

This trend will directly affect spending in the U.S. for child goods and services. That includes items like diapers, strollers, or clothes... and it also means less money spent on child care.

Right now, one company at the heart of early child care is Bright Horizons Family Solutions (BFAM). It's the largest provider of employer-sponsored child care in the country.

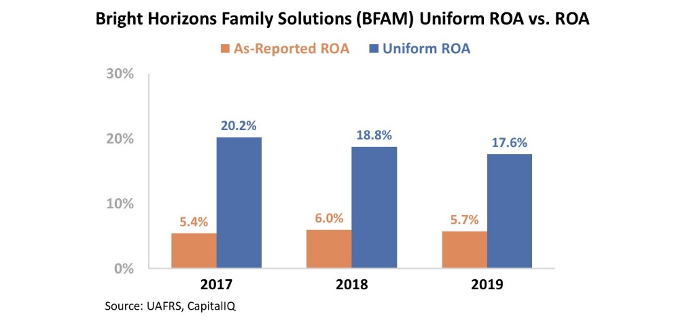

Because of its value to parents, it generates a high return on assets ("ROA"). Although its as-reported ROA was only 6% last year, Uniform Accounting shows that Bright Horizons' real profitability was higher at 18%.

We highlighted this dislocation back in October... but today, let's revisit Bright Horizons with more context on the upcoming birth dearth.

The big question now is if Bright Horizons can grow with fewer children in society. It appears that demand for its services will decline, and that could hurt the company's profitability.

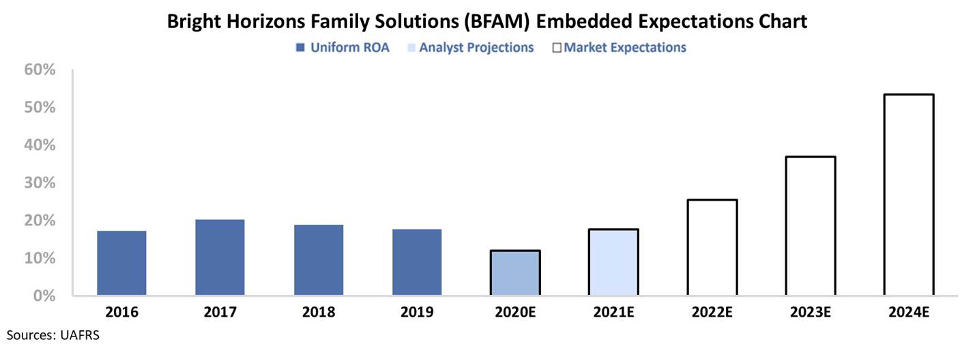

To see what the market is expecting Bright Horizons to accomplish in the coming years, we can use our Embedded Expectations Framework.

Most investors determine stock valuations using a discounted cash flow ("DCF") model, which takes investors' assumptions about the future and produces the "intrinsic value" of the stock.

However, here at Altimetry, we know models with garbage-in assumptions only come out as garbage. Therefore, we turn the DCF model on its head. Instead, we use the current stock price to determine what returns the market expects a company to make.

In the chart below, the dark blue bars represent Bright Horizons' historical corporate performance levels, in terms of ROA. The light blue bars are Wall Street analysts' expectations for the next two years. Finally, the white bars are the market's expectations for how ROA will shift over the next five years.

Right now, Wall Street analysts are expecting Bright Horizons' Uniform ROA to fall this year as the pandemic pressures profitability. Then, analysts expect a rebound to 17% in 2021.

After that, the market is pricing in Bright Horizons Uniform ROA to more than double... reaching 48% by 2024.

This would be astronomical growth, with record returns for the company. But with a declining customer base, it would be difficult for Bright Horizons to grow profitability at the rate the market is currently pricing in.

Uniform Accounting shows how excessively bullish Bright Horizons' expectations are. The company needs positive tailwinds to ramp up profitability quickly... likely greater than the significant value it provides for parents, which we mentioned back in October.

When factoring in a likely birth dearth, Bright Horizons may struggle to meet those sky-high valuations... so investors shouldn't be surprised if the company fails to hit those profitability levels.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

December 8, 2020

Historians and journalists peg 1946 as the 'official' beginning of the Baby Boom...

Historians and journalists peg 1946 as the 'official' beginning of the Baby Boom...