Political challenges come with a speedy vaccine rollout...

Political challenges come with a speedy vaccine rollout...

As the Delta variant sweeps the world, investors are reminded about the importance of vaccinations to bolster the economy.

On Monday, the market tumbled nearly 100 points intraday as the number of coronavirus cases are on the rise. While the market tends to run and hide at any mention of the virus, we knew this would happen.

The Moderna (MRNA) and Pfizer (PFE) vaccines are up to around 95% effective for those who receive both doses. But as bars reopen and masks are removed, we see more people contracting the coronavirus.

It is the unvaccinated people, who make up the bulk of new infections. As the country reopens, it's inevitable that those resistant to or unable to get the vaccine would follow the masses into bars, parties, and sporting events.

With eased-up mask restrictions, it was inevitable for many unvaccinated individuals to leave their masks at home.

On the bright side, we see that the vaccines are working exactly how they are intended.

Even amid the current spike, most experts agree that the fastest way to get the entire world back on track is to vaccinate as many people as quickly as possible.

While there are political and ethical challenges with reaching a state of vaccine-induced herd immunity, there are business questions, too.

Such questions take us to the core of why America leads the world in "drug design" innovation: Why our drugs are so expensive? How will a speedy vaccine rollout change the pharmaceutical landscape forever?

The morals of Big Pharma and patent rights...

The morals of Big Pharma and patent rights...

There has been considerable debate about how to make a speedy and widespread vaccine rollout happen.

In the U.S.'s mostly privatized health care system, companies run astronomically expensive research and development ("R&D") pipelines with the hope that one day, years later, they will bring world-changing drugs to the market.

These companies expect to be rewarded handsomely for their efforts during the pipeline process. Before embarking on developing a new drug, companies need assurance that competitors won't copy their innovations and steal their market share.

That has meant some of the most stringent intellectual property ("IP") protections in the world.

With total ownership over their IP, American pharmaceutical companies have more incentive to work on expensive, moonshot drugs for the most difficult-to-treat diseases.

Pipelines typically take three to 10 years – far longer than we could afford given the coronavirus crisis.

The entire pharma industry practically put all of its other projects on hold, and with ample government funding, the race was on to develop the first vaccines that would claim most of the market share. We know the winners – Pfizer, Moderna and, to a lesser degree, Johnson & Johnson (JNJ).

The race to the vaccine is won, but the rollout is taking an eternity.

Some think that IP laws are to blame, and perceive these regulations as preventing other companies from jumping in and using more production systems and distribution channels to aid in the effort.

The cost of this is greater than just the economic burden of a slower reopening. The longer the virus circulates, the higher the chance of it mutating into something resistant to the vaccines.

This would eradicate the progress we've made toward reopening, let alone more deaths and political unrest around the world.

With its army of lobbyists, Big Pharma has fought back hard against the mere idea of loosening patent protections. These companies argue this would create risks to the patent protection concept globally, reducing innovation, which would cause more people to suffer down the road from other hard-to-treat viruses and diseases.

But as a recent article in The Economist points out, it may be worth asking: How productive are aggressive IP laws?

As it turns out, the rate of return on pharmaceutical R&D in the U.S. fell from 10% a decade ago to a dismal 2%, well below the cost of capital. Worse yet, the average pipeline cost rose by 66% over the same period to more than $2 billion.

Given the global crisis and risks of a prolonged rollout, the case for loosened patent protections as a one-time exception is a strong one.

Or so you might think…

Looking deeper into Big Pharma's pocketbook...

Looking deeper into Big Pharma's pocketbook...

To understand the reality on the ground, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the pharmaceutical industry as a whole.

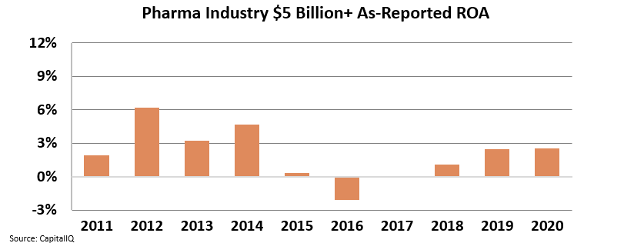

We filtered for pharma companies with a market cap of more than $5 billion, industry giants with lobbying power. From our study, we see that returns have collapsed from 2012 highs, with a disappointing recovery since then. The average return on assets ("ROA") has been around 2% for the past decade.

These results resemble those reported by The Economist. But instead, we are using ROA, whereas they are using return on R&D spending.

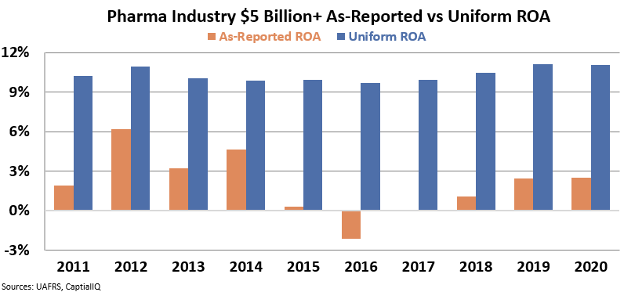

The Economist, like most other publications, relies on as-reported metrics. These have flaws that make it impossible to compare companies on an apples-to-apples basis. It also causes the tendency to underestimate true dollar-in, dollar-out economic productivity.

Here at Altimetry, we have made it our mission to provide our subscribers with numbers that represent economic reality...

Here at Altimetry, we have made it our mission to provide our subscribers with numbers that represent economic reality...

We make hundreds of adjustments to financial statements to filter through the noise and properly understand how different companies operate and utilize resources.

When we look at the same set of companies using the right Uniform Accounting metrics, we can see why these pharmaceutical companies are fighting so hard to protect profits. Big Pharma's ROA over the past decade hasn't been 2%. It's actually been more than 10%.

The decade-long slowdown reported by The Economist is a falsehood. True economic returns have been consistent and robust. It's impressive for a sector as risky as pharmaceuticals.

ROA around 10% is respectable. But it's far off the returns we see with Big Tech. The industry as a whole is being weighed down by early-stage startups with no cash flows.

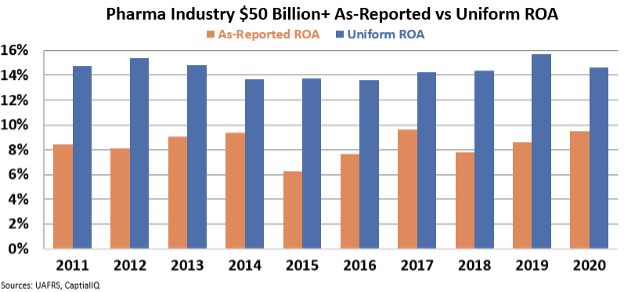

Now, let's look at only those firms with market capitalizations greater than $50 billion, such as Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Eli Lilly (LLY), to name a few. These are the largest industry moguls with cashflow-positive R&D pipelines.

With Uniform ROAs averaging around 14% over the past decade, these companies perform better than the corporate average.

These companies may already have a cash-cow drug that pays for deeply expensive oncological or neuroscience research efforts that may not turn a profit for decades.

Whether temporary patent protections should be lifted to combat the coronavirus crisis is a complicated political question.

We can say, however, public perception of the inefficiency of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry is flawed by inaccurate as-reported definitions for R&D and cash returns.

Regards,

Rob Spivey,

July 21, 2021

P.S. Our Altimeter tool breaks down the true fundamentals... Using the power of Uniform Accounting – The Altimeter shows users easily digestible grades to rank stocks based on their real financials.

The Altimeter is a veritable "stock truth detector" that allows you to see the full grading for more than 4,000 other U.S.-listed companies – including the real valuations for Big Pharma companies, such as Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer.

Get more details about The Altimeter right here.

Political challenges come with a speedy vaccine rollout...

Political challenges come with a speedy vaccine rollout...