Dear reader,

Many theological studies focus around the idea of cosmic dualism.

This, of course, is the concept that the universe is governed by opposing forces.

There are many manifestations of dualism...

Good and evil... the Taoist and Zen concept of Yin and Yang – which comes to represent a number of opposing forces (light vs. dark, cold vs. warm, feminine vs. masculine, etc.)... Even Isaac Newton's Third Law of Motion, "For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction," represents this idea in the physical world.

Ultimately, each of these examples represents balance. Give and take, push and pull, win and lose.

We could discuss the philosophical side of dualism all day... but this is an investing newsletter, after all.

The truth is, these concepts apply as much to the business world as the spiritual one. And they especially apply to investing... When a stock trades hands from a seller to a buyer, one party will "win" and one will "lose."

The same is true with industry competition. For every iPhone sold, there's a Samsung Galaxy still sitting on the shelf, and vice versa.

Today, I want to focus on how this dynamic plays out during a recession...

There's a common misconception that all companies perform worse during a recession... and that the responsible choice as an investor is to pull your money out of equity and "push" it into bonds, gold, or even cash.

The thought is – especially in consumer industries – all companies lose out when the economy struggles. However, this violates the principle of cosmic dualism... and I'll show you why today.

Let's take the automotive industry as an example. One of the first things to go during tough times is the notion of buying a new car. As a result, pretty much every major automaker is already pricing in declining car sales when the recession finally hits.

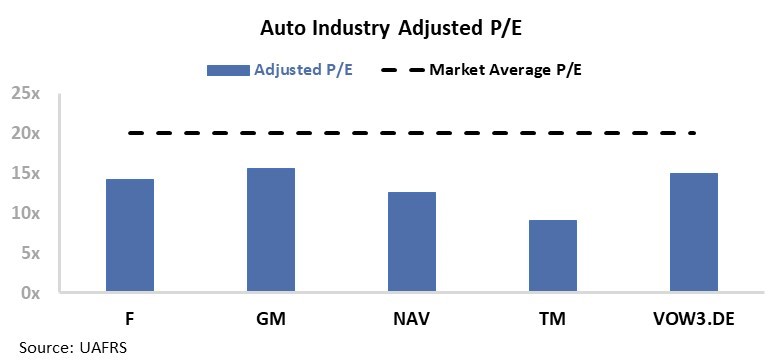

Take a look at the chart below comparing the price-to-earnings ("P/E") ratios of major automakers Ford Motor (F), General Motors (GM), Navistar (NAV), Toyota Motor (TM), and Volkswagen (VOW3.DE)... all are trading at a discount to the market.

But let's think about the other side of the equation... Consumers are buying fewer new cars, but overall vehicle usage isn't falling nearly as quickly. People still need to get around, and our population continues to grow.

Of course, when people aren't buying new cars, they need to make their existing cars last that much longer. It's much cheaper fitting your 2003 Toyota Camry with a new air conditioner and a set of fresh brake pads than buying the 2020 model (at a base retail price of $24,295).

Clearly, it makes more sense for consumers to repair and maintain their old cars.

When that happens, the economic "balance" shifts away from automakers and towards aftermarket auto-parts companies.

And LKQ (LKQ) is in a position to take advantage of this shift.

LKQ is one of the largest distributors of automotive components and replacement parts in the world. It distributes doors, gas tanks, spark plugs, radiators, and everything in between.

What traditional automakers lose during a recession, LKQ stands to gain.

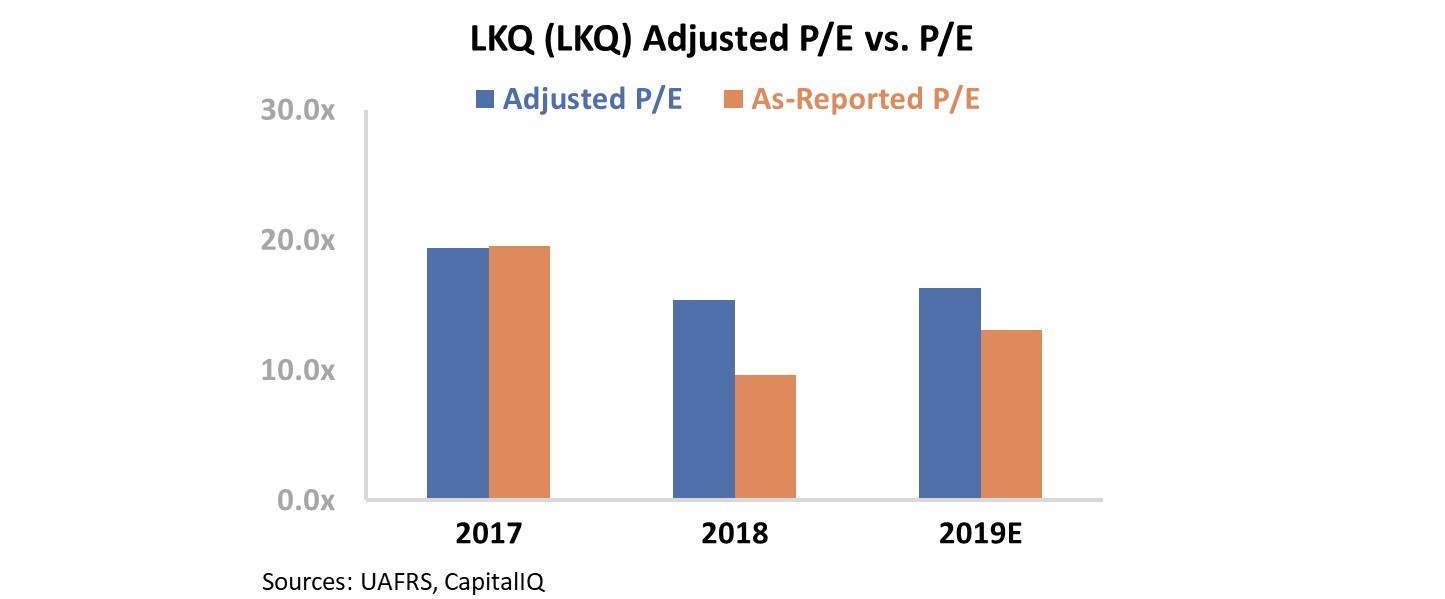

However, investors view LKQ like the rest of the auto industry. The company also trades at a discount to the market at a P/E ratio of 16 – in line with the likes of Ford and GM.

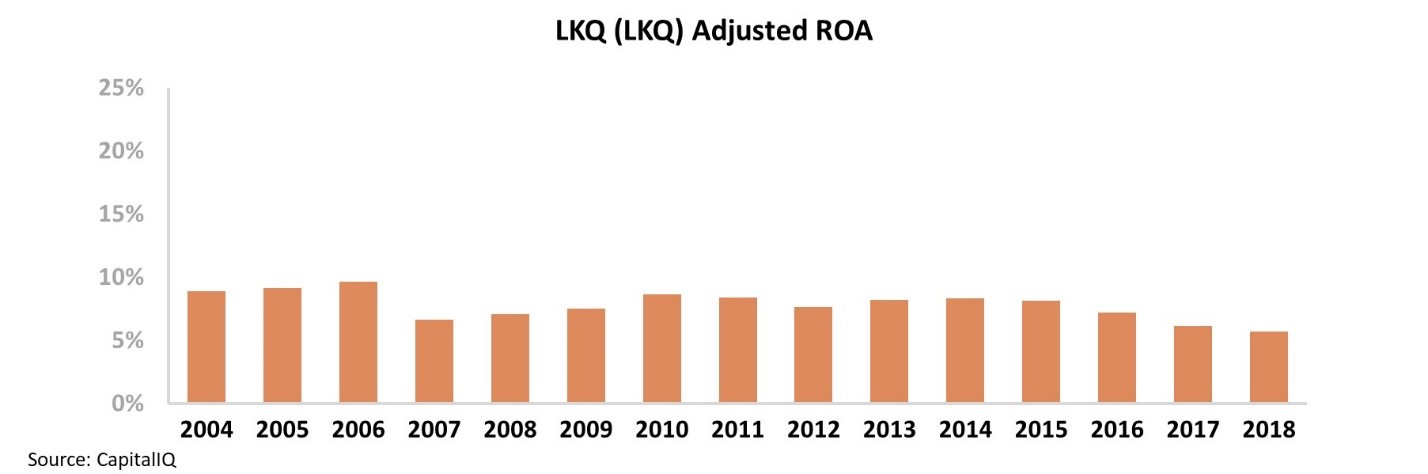

When looking at as-reported financial data, LKQ looks a lot like other automakers. Looking at the last 15 years, we can see how the company performed through the Great Recession. On an as-reported basis, LKQ looks like a stable but weak company with an average return on assets ("ROA"). Since the Great Recession, it has seen its ROA remain in the 6% to 8% range. Take a look...

Moreover, traditional accounting metrics make it look like LKQ struggled during the last recession – with its ROA dropping from 10% in 2006 to a range of 6% to 7%. And this pattern looks to be repeating, with LKQ's ROA reaching 10-year lows last year.

However, once we apply our Uniform Accounting metrics – adjusting for inconsistencies like treatment of goodwill and operating lease capitalizing versus expensing – the distinction becomes obvious.

Not only is the LKQ's Uniform ROA far stronger than as-reported metrics would suggest, but the company's performance improved to peak 17% levels in 2007 and remained strong throughout the recession.

LKQ is being incorrectly compared to automakers without good reason. Aside from both dealing with vehicles, LKQ and these companies have very little in common... and in fact benefit from opposite economic conditions.

LKQ is well positioned for any negative cycle in the auto industry. It shouldn't be valued in the same way as the automakers.

Tracking the ebb and flow of capital and performance between different companies can be difficult, especially when you're looking at misleading data. When using Uniform Accounting, it's much clearer how to find balance in the markets.

Regards,

Joel Litman

November 5, 2019