It's been nearly 24 years since the Federal Reserve began its secret 'inflation targeting'...

It's been nearly 24 years since the Federal Reserve began its secret 'inflation targeting'...

During the summer of 1996, the 12-member Federal Open Market Committee ("FOMC") sat down for one of its eight annual meetings.

One of the items on the committee's docket was to discuss inflation – just as common of a topic in the 1990s as it is today.

However, at this particular meeting, the various governors and bank presidents had an entirely new question about the subject – specifically, whether the U.S. should be "inflation targeting."

Most people know that the U.S. currently aims for annual inflation around 2%... but don't know that this practice was only introduced within the past 30 years.

In March 1990, New Zealand became the first country to try inflation targeting with its inaugural Policy Targets Agreement.

Reserve Bank of New Zealand Chief Economist Arthur Grimes tried to win approval to lower inflation through whatever means necessary by coining the phrase "zero to two by '92" – meaning the country would reach its target of 0% to 2% inflation by 1992.

There were short-term growing pains for the initiative – unemployment shot up and took many years to recover. Yet New Zealand reached its inflation target in 1991, and many countries followed suit in subsequent years.

The U.K., Canada, and Australia were among the first to adopt inflation targets, and the U.S. followed soon after.

This brings us back to the FOMC summer session, during which Janet Yellen – a fairly new Fed governor at the time – recommended the U.S. target 2% inflation to Chairman Alan Greenspan.

While it wasn't until 2012 that Chairman Ben Bernanke formally "set" the 2% target, it's largely believed that the Fed was targeting 2% inflation in secret under Greenspan.

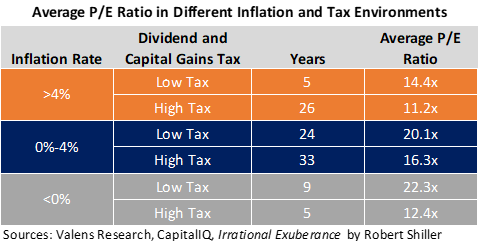

We've previously discussed the importance of managing inflation to keep markets strong. In the October 21 Altimetry Daily Authority, we looked at market valuations under different inflation and tax environments.

As we explained, inflation rates greater than 4% generate significantly lower market valuations because investors keep less of their earnings. In the chart below, you can see these lower price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios...

The Fed has done a good job of maintaining inflation near the target for many years now, especially since Bernanke officially announced the target to the public.

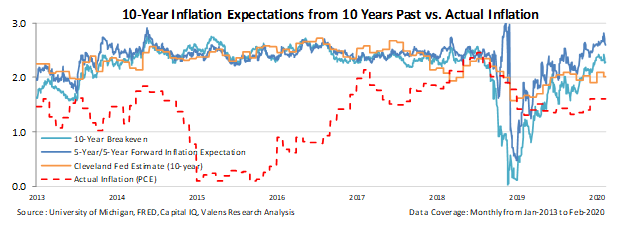

That said, even the most well-respected, well-informed economists have a hard time predicting inflation rates...

Many sources – ranging from the University of Michigan to the Cleveland Fed – publish their inflation estimates for one, five, and 10-year periods to provide the public with more data to understand how the economy might be impacted.

Over time, we can test these estimates versus what actually happens to see how accurate some of our best economists are at predicting inflation. As you can see in the chart below, inflation has consistently fallen below expectations...

Luckily, this is a good thing for investors.

Tying this back to the stock market under different inflation rates, we can see that stocks tend to command lower valuations in higher-inflation environments. Said another way, the market performs better when inflation remains low.

We also know that, generally speaking, the stock market makes use of information that's publicly available – including expectations for future inflation rates.

When investors believe inflation will be greater than 2%, this can be damaging to stock valuations. Investors think that more than 2% of their gains are being eliminated.

When inflation ends up being lower than originally predicted, investors end up keeping a larger portion of their gains – which is a tailwind for valuations. As investors keep having to adjust down expectations for inflation, that also boosts warranted valuation multiples.

As we continue trudging along in the current bull market, low inflation should carry on as a driver of strong valuations.

Just last week, I had a conversation with an institutional client about this issue and its implication for the economy and market...

Just last week, I had a conversation with an institutional client about this issue and its implication for the economy and market...

There could be real disruption to supply chains in the short term with the coronavirus outbreak. This is why the Fed cut rates... and it has been a widely discussed overhang as China's manufacturing base gets back on track.

A supply chain disruption creates product scarcity, which also creates inflation. When supply doesn't match demand, prices will rise until demand aligns with supply.

That could be a more brief disruption, which could bring inflation to the forefront for a shorter-term period of time – assuming individuals don't just choose to switch to different types of goods, or go without them entirely (which is also a possibility).

But the bigger question that one of the analysts at a meeting we had with an institutional client north of Boston last week posed was about longer-term inflation...

If the Fed isn't going to raise rates (because inflation isn't likely to be an issue), does that mean we could have an easy-credit environment for even longer than we previously thought? Here at Altimetry, our outlook is for this period to likely stretch until late 2021 or early 2022.

The client's question was more so about the Fed targeting interest rates. The central bank really only raises interest rates when it's concerned about the economy overheating, which is generally indicated by higher inflation.

If inflation never comes, and the Fed never raises rates, can't companies continue to borrow at these more favorable low rates?

And if companies and individuals never get closed out of credit markets, and credit destruction is the main driver of a real recession and deep bear market... couldn't companies continue to roll over their debt for a longer period of time, thus fueling economic growth to 2025 or even to 2030?

It's a strange line of thought to take when the market is in the midst of a significant pullback and people are concerned about global growth... but the answer could be yes.

Here at Altimetry, we'll continue to listen to the data... and the numbers don't say explicitly that just yet.

But in the midst of this panic, it's worth remembering that there's a bull case out in the market... even though no one is paying attention to it.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

March 9, 2020

It's been nearly 24 years since the Federal Reserve began its secret 'inflation targeting'...

It's been nearly 24 years since the Federal Reserve began its secret 'inflation targeting'...