Coronavirus hasn't become an excuse for guidance, and that's a good sign...

Coronavirus hasn't become an excuse for guidance, and that's a good sign...

Market-research firm CB Insights conducted an analysis of recent earnings call transcripts and identified only six instances of "coronavirus" being mentioned on calls since the outbreak. The analysis also showed that the usage of the term "pandemic" hadn't seen a major spike.

Compare these results to earnings calls in the third quarter of 2009, when the H1N1 swine flu broke out... During those calls, discussions about a pandemic and how it could impact earnings spiked significantly.

In terms of what this means for corporate guidance, this is a good thing...

Companies like to take any opportunity to attribute concerns about weakness to external factors they can't control – be it weather for a retailer, logistical partner issues for a weak product launch, or the timing of a holiday in the middle of a week suppressing demand in the travel industry.

The fact that companies aren't looking for coronavirus excuses to lower guidance may be a sign that they are still bullish on their outlook. That's a positive signal for earnings growth for 2020... and for the overall market.

Let's start today with a brief philosophical discussion...

Let's start today with a brief philosophical discussion...

Many of our employees have an interest in philosophy. Some, including Director of Research Rob Spivey, went as far as to pursue a minor in philosophy in college.

Unsurprisingly, we often find ourselves looking at finance and investment ideas on a philosophical level. While not always a useful exercise, it has sometimes led to interesting conclusions.

Today, we'll connect our featured company to a philosophical thought experiment: the "Ship of Theseus"...

Theseus was an important hero in early Greek mythology – most famous for defeating the Minotaur in a labyrinth in Crete. After he returned to Athens, the citizens of the city preserved his ship in his honor.

In each subsequent year, the Athenians would ceremoniously sail the ship. Over time, some of the wood became damaged. In order to keep the ship seaworthy, the Athenians would replace any damaged wood with new materials.

Philosophers gave rise to the question – at what point is the Ship of Theseus no longer the same ship? If every piece of it were to be individually replaced over many years, could it still be called Theseus' ship?

Regardless of the answer (of course, there is no correct answer), this question relates to some of the companies we've highlighted in the past, and it certainly relates to today's business...

Last week, we discussed chipmaker Texas Instruments (TXN) – which started as a seismology company before transitioning to basic chipmaking and cornering the calculator market to its current form. It's a leader in the analog chip market.

With all of these twists and turns, we unpacked whether Texas Instruments could still be considered the same company that it originally was... and what implications that has for investors.

Today, let's examine another company that sold the last vestige of its original business – begging the question of whether it can still be viewed as the same company at all.

Emerson Electric (EMR) began as an electric-motor manufacturer in 1890. It was the first company in the U.S. to sell electric fans, and it went on to grow into a multinational business with all kinds of different products for consumers and industrial customers.

But looking at the company's current two operating segments, you would have no idea that Emerson ever set foot in the motor business...

In 2017, Emerson sold off its last stake in its historic Motors, Drives, and Electric Power Generation businesses to Japan-based Nidec. This wasn't a complete surprise – in fact, in 2010, the company sold its U.S. Motors brand to Nidec as well.

Emerson management has been trying to fully focus the business on high-growth areas like machine automation, programmable controllers, and more tech-enabled end markets.

Whether or not you believe the company can still be called Emerson Electric on a philosophical level, investors don't seem to notice the difference...

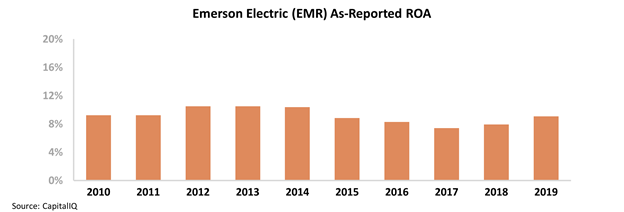

Since the company sold the last of the motor business, its returns have hardly moved. Historically, Emerson has seen average, somewhat cyclical profitability – with its return on assets ("ROA") ranging between 7% and 11%. This has held true even after getting rid of the legacy motor business – Emerson's ROA has only improved from 8% in 2017 back to 9% last year.

But once we make the proper adjustments, we can see this isn't the case...

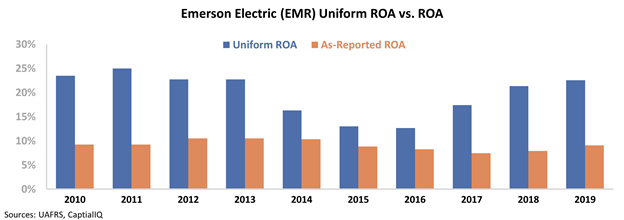

For a company like Emerson – one that has historically made a number of acquisitions and divestitures – GAAP accounting principles create inconsistencies that make it nearly impossible to look at profitability. Once we adjust for all of these distortions – including the treatment of acquisition-related goodwill, non-cash stock option expense, and operating leases – we can see that Emerson's departure from its historic motor business has turbocharged returns...

Rather than seeing its ROA remain flat around corporate-average levels since 2016, Emerson's Uniform ROA has nearly doubled from 13% in 2016 to 23% last year. Take a look...

While it appears that the divestiture of Emerson's motor business hasn't impacted the company, we can instead see that management's focus on high-growth areas has actually benefited the company significantly.

With such a large difference between as-reported and Uniform metrics, it's impossible to think you can properly analyze a company using GAAP metrics alone... particularly for an evolving business like Emerson Electric.

Regards,

Joel Litman

February 19, 2020

Coronavirus hasn't become an excuse for guidance, and that's a good sign...

Coronavirus hasn't become an excuse for guidance, and that's a good sign...