The current discussions about 'debt forgiveness' programs have a historical precedent...

The current discussions about 'debt forgiveness' programs have a historical precedent...

Here at Altimetry, we employ several current college students and recent graduates, thanks to our relationship with the great co-op program at Northeastern University. (As a graduate of the program myself, I'll admit I'm biased in talking about how great it is.)

Due to this proximity, we've heard a lot about a specific set of proposals in the Democratic presidential debates recently.

A few of the Democratic candidates have floated plans to address rising student-debt levels in the U.S. As we highlighted in yesterday's Altimetry Daily Authority, student debt is at its highest level ever.

These plans vary in scope and scale, but two candidates in particular – Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren – have called for massive "student loan forgiveness" plans.

While "forgiveness" seems to be the current term for this idea, this is actually a historical concept which has existed for more than 2,000 years.

Dating back to the writings of the Old Testament, the "jubilee" is an age-old debt forgiveness program. It's said that approximately every 50 years, those who observed certain forms of Judaism and Christianity would forgive all forms of debt (not just economic) and start anew.

The jubilee is usually interpreted as a religious and spiritual "forgiveness program," but some people have taken it more literally...

After the Great Recession, Iceland tried a controlled form of debt jubilee. Rather than forgiving all debt, the government targeted inflation-linked mortgages – some of which rose in excess of 30%.

The program was small and received mixed reviews. Here in the U.S., it's much harder to predict the impact of a student debt forgiveness program, given its unprecedented size and number of borrowers and lenders.

But I know where our recent graduates and student employees stand on the issue...

What are your thoughts on student loan debt forgiveness? Let us know at [email protected].

The economy changes quickly...

The economy changes quickly...

It's hard to stay relevant in a fast-moving economy. Companies can go from successful to bankrupt nearly overnight.

We've written before about some winners who have managed to adapt in order to stay relevant...

In our article on tech giant IBM (IBM), we highlighted how Japanese video-game firm Nintendo (NTDOY) began as a playing-card company and that French carmaker Peugeot (PUGOY) originally made coffee grinders.

These were necessary transformations – the above companies likely wouldn't exist if they hadn't reinvented themselves.

It's comical to see how wildly some businesses have shifted in their history. For example, Finnish electronics company Nokia (NOK) began as a single paper mill during the mid-1860s.

Along the way to producing phones and smart TVs, the company made everything from electricity to rubber boots and gas masks.

Nokia is certainly an extreme example, but it shows why corporate reinvention is so important. The company nearly went bankrupt in the early 1900s but has been able to survive to this day through a winding road.

Aside from being a fun anecdote, these large transformation efforts are also an important case study for investors.

When evaluating a stock, it's important to compare the underlying company to similar "peer" businesses. Without a comparison to other firms in the same industry, it can be difficult to determine if a company is strong or weak.

For example, utility companies tend to have low returns due to heavy regulation, while pharmaceutical firms are usually much more profitable.

As a result, it's much less useful to compare businesses in different industries than it is to more direct peers.

For instance, investors should compare returns between pharmaceutical giants Gilead Sciences (GILD) and AbbVie (ABBV) rather than with a utility like Exelon (EXC).

That said, when a company transforms itself so dramatically, valuations sometimes fail to keep up.

This appears to be the case with Texas Instruments (TXN)...

You may think of it as a calculator company, but Texas Instruments is far more than that... and it started in a completely different business.

Before it was known as Texas Instruments, the company built seismographs – tools for measuring ground movement from earthquakes or for oil and gas exploration and military use.

Within the past two decades, Texas Instruments has always been a chipmaker. While it does make full consumer electronics like calculators, this makes up less than 10% of the company's total sales.

Especially in recent years, Texas Instruments has been investing more into its analog business – the segment making chips that convert analog signals into digital ones.

This is a higher-margin business than the company's older units, but you likely couldn't tell based on its recent performance.

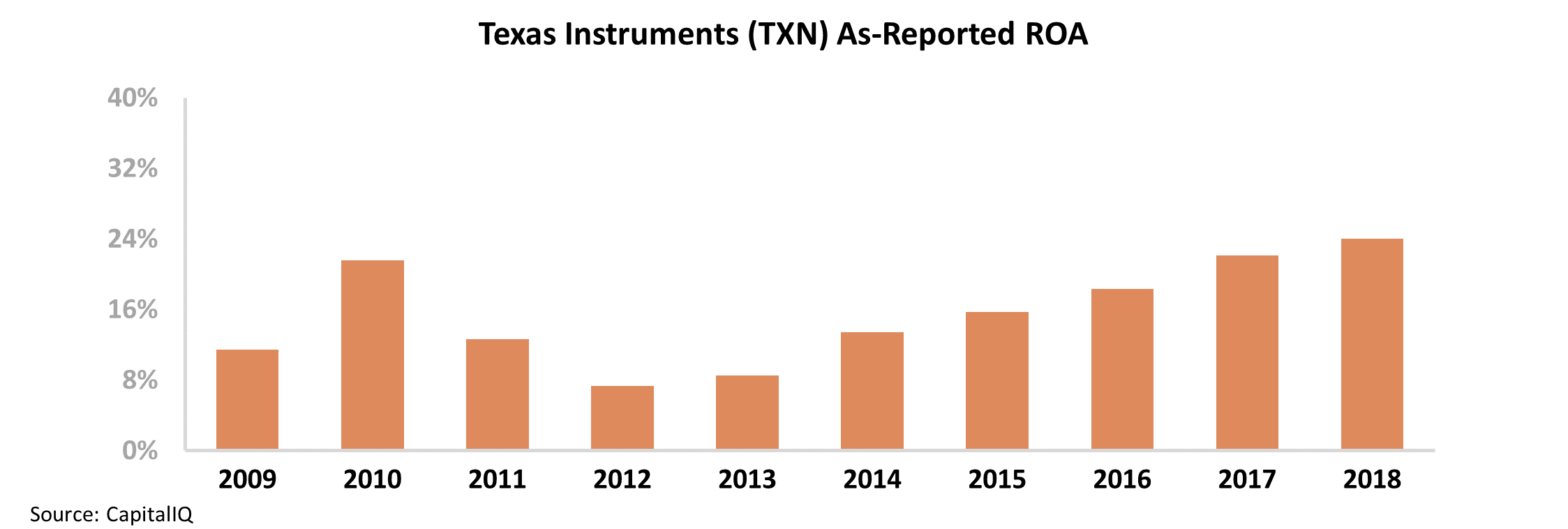

Over the past decade, Texas Instruments has seen its return on assets ("ROA") range between 7% and 24%. Take a look...

While the company's ROA has improved substantially over the past several years, we would categorize these returns as cyclical – explained by cycles in the economy – rather than transformative.

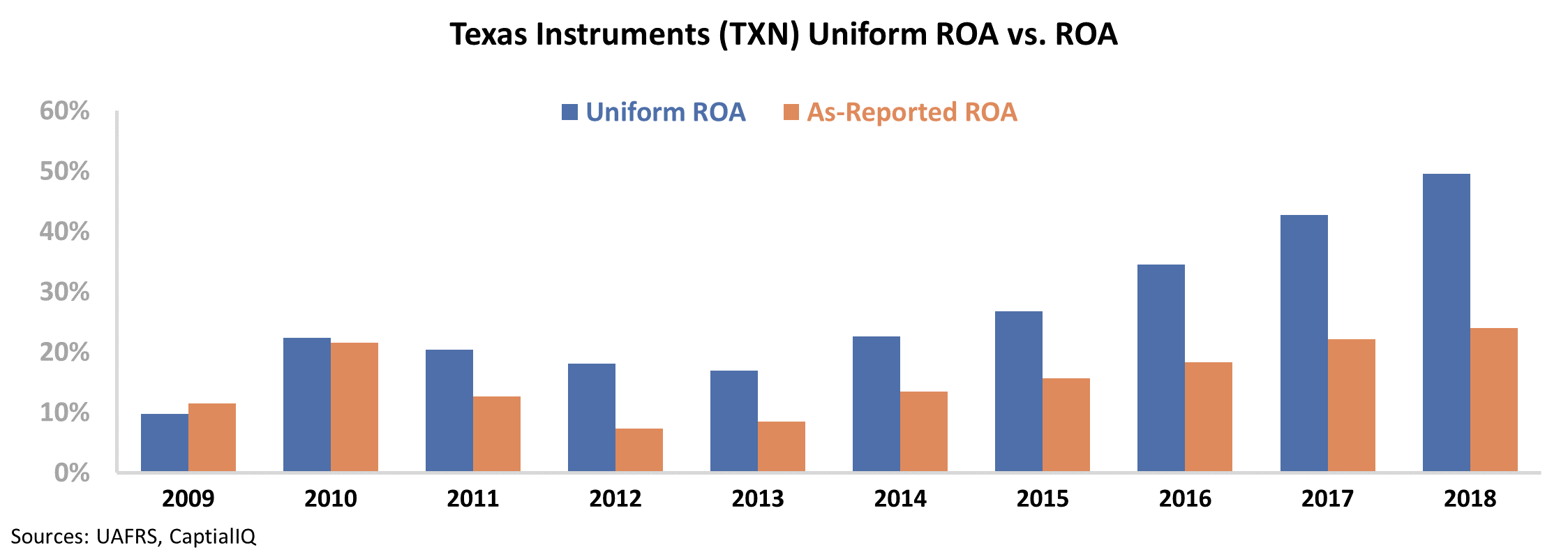

That said, once we apply our Uniform Accounting metrics, we can see that Texas Instruments has successfully transformed its business over the past decade...

After adjusting for misleading accounting practices that cloud as-reported metrics – items like the treatment of goodwill, capitalizing versus expensing research and development (R&D) costs, and stock option expense – we can see the real impact of Texas Instruments' investments into analog.

While still somewhat cyclical, we can see that the company's returns have more than doubled over the past five years – from a Uniform ROA of 23% in 2014 to 50% in 2018.

At these levels of profitability, Texas Instruments no longer fits the return profile of a typical semiconductor company.

Even though as-reported metrics make it look like a cyclical chipmaker, we can see how Texas Instruments has truly transformed when we look at the Uniform metrics.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

February 11, 2020

The current discussions about 'debt forgiveness' programs have a historical precedent...

The current discussions about 'debt forgiveness' programs have a historical precedent...