A bad industry beats a great manager every time, but maybe not a great investor...

A bad industry beats a great manager every time, but maybe not a great investor...

Last week, the legendary Warren Buffett announced that he was selling Berkshire Hathaway's entire portfolio of newspapers – including the Buffalo News – to Lee Enterprises.

The Buffalo News is integral to Buffett's lore. He purchased the paper in 1977 and counted longtime publisher Stanford Lipsey as a close friend. The Buffalo News was one of the assets that threw off cash flow for Buffett for many years and helped fuel Berkshire's growth.

But like many newspapers in the U.S. and across the globe, the News had fallen on hard times and was struggling to sustain itself. While Buffett had made a great deal on the cash flow that his newspaper holds generated over decades, he could see the writing on the wall.

But Lee Enterprises has a vote of confidence from Berkshire. As Buffett said regarding the sale, "We had zero interest in selling the group to anyone else for one simple reason: We believe that Lee is best positioned to manage through the industry's challenges."

It's debatable if Lee will actually succeed... As the saying goes, "A bad industry beats a great management team every time." But Buffett may have designed a way where he can still make money, no matter what happens...

As part of the deal, Lee is paying Berkshire $140 million, and Berkshire is giving Lee a $576 million loan. The loan will yield 9% a year – a healthy return for Berkshire. If Lee doesn't succeed, Buffett may end up owning his newspapers again, considering the debt he owns in Lee now. And if Lee does buck the trend, Buffett will be paid handsomely for betting on the company.

It just goes to show that while not even the best managers can win against a bad industry, investors can still make money if they're smart about how they invest.

In the January 13 Altimetry Daily Authority, we discussed the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey ('SLOOS') and its connection to recessions...

In the January 13 Altimetry Daily Authority, we discussed the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey ('SLOOS') and its connection to recessions...

As a quick refresher, we explained that the Federal Reserve conducts a quarterly survey of banks in the U.S. to monitor whether these institutions are tightening or loosening their lending standards.

At this point, lending standards are fairly loose... which is a good sign for the economy. And these standards have held fairly steady over the past several quarters, with only a modest tightening occurring in the latest SLOOS report.

Lastly, we noted that if lending standards begin to tighten significantly – meaning it becomes difficult to access credit from a borrower's perspective – then it's time to worry.

Today, we're continuing the conversation around lending standards by highlighting one of the main drivers that causes banks to tighten their standards...

While it's easy to consider banks as their own entities, they're still ultimately comprised of people.

As a result, banks are subject to many of the same qualities any human would have – including the potential for human error, the desire to innovate, and "loss aversion."

Loss aversion simply means that it feels worse to lose money than it feels good to make money. Imagine how it feels to find a $20 bill on the ground when you're on a walk... There's a moment of excitement, and then you pocket the money and go on with your day.

Now, imagine how it feels walking into a store, reaching into your pocket to get a $20 to pay for something, and realizing it's not there. You can pay with your credit card, but you're already imagining yourself spending the next 10 to 15 minutes playing back your day to figure out where you lost that $20. It hurts much more than finding $20 feels.

This leads humans – and banks – to be more careful once they feel that sense of loss.

While you won't find them loosening credit standards haphazardly, banks are quick to tighten lending standards when faced with losses stemming from bad loans.

Because of this connection, a surefire way to tell when banks are likely to start tightening their lending standards is to monitor their loan losses.

Banks always reserve a small percentage of their loans for losses... but when that number starts rising, banks act conservatively and begin tightening lending standards.

As their risk increases, banks are required to hold more money on their balance sheets as "loan loss reserves." This is money that cannot be put to use, which makes the banks less efficient. In order to avoid this, banks react quickly as loan losses rise.

Also, rising charge-offs can be a sign that lending standards were too loose – again, banks are quick to remedy the situation...

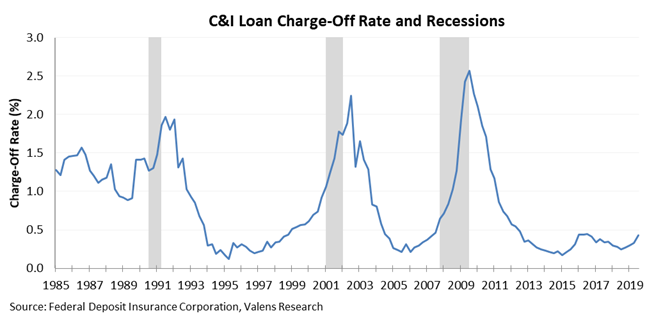

And one good way to monitor this is Commercial and Industrial (C&I) loan charge-offs. C&I loans are given out specifically to businesses, and they're a good proxy for corporate credit.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation ("FDIC") monitors the percentage of C&I loans that default on a quarterly basis. When C&I charge-off rates start to rise, we're likely to see banks tighten lending standards.

The chart below highlights C&I charge-off rates since 1985, along with the past three recessions. As you can see, these rates rise to a certain level leading up to a recession. Over the past few quarters, charge-off rates have begun ticking higher – this aligns with the small tightening in credit we have seen. That said, current charge-off rates remain near the low end of historical levels...

As long as charge-off rates remain near current levels, tougher access to credit is unlikely. This is one of the main reasons SLOOS has stayed put over the last several quarters.

Based on current charge-off rates, we don't see a substantial risk of banks tightening their credit standards... but if these levels increase, it's a warning sign. We'll be closely monitoring this on a quarterly basis, as it can be among the first signals that fundamentals are shifting in credit markets. But for now, our overall outlook is still positive.

Regards,

Joel Litman

February 3, 2020

A bad industry beats a great manager every time, but maybe not a great investor...

A bad industry beats a great manager every time, but maybe not a great investor...