U.S. corporate credit profiles look healthy, but China may be a different story...

U.S. corporate credit profiles look healthy, but China may be a different story...

In yesterday's Altimetry Daily Authority, we discussed how the U.S. economy and market remain strong – even in the face of the threat of the coronavirus outbreak impacting global growth.

But as Bloomberg reports, the risk of a credit crunch may be different in China...

Credit in the country has already been an issue. Many small- and medium-sized Chinese companies have limited cash buffers relative to operating obligations. Without the banks and government providing incremental liquidity, they may run into problems as China's economy slows from the outbreak.

Fortunately, the Chinese are aware of the risks, and are attempting to get some of these companies credit – in particular, ones who have anything to do with the coronavirus containment effort – to avoid creating a vicious circle of failing businesses increasingly destroying demand.

But we should note that even if we do see credit destruction in China, it isn't a more broad global contagion. The Chinese financial market – and overall economy – remains closed to the rest of the world even as the country has become the second-largest economy on the planet.

Limited Chinese debt is owned externally, and it's challenging for investors outside China to own mainland stocks.

There's an old saying that when the U.S. catches a cold, the world gets the flu. This is due to how dependent the rest of the world historically has been on U.S. economic growth to drive overall global growth. Fortunately today, the same can't be said for China because of how much it hasn't opened its financial markets to the world.

It's one of the 'safest' public investments in the oil industry...

It's one of the 'safest' public investments in the oil industry...

And it's not exactly what you're thinking of.

Since the Great Recession, we've seen the ups and downs inherent in commodity businesses with oil. Prices surged following the market slump. Remember those expensive trips to the gas station?

And the same trend happened in the decade before the Great Recession...

It was a great time to be exposed to oil companies in the stock market. From drillers to refiners, and to consolidated companies like ExxonMobil (XOM) that did it all, oil and energy firms were generating huge fortunes.

This led to massive investments in different oil projects, including pipelines that could transport oil and gas across long distances.

It was a prosperous time in the energy industry, and the energy companies all tried to make the most of it – some by getting more exposure to the commodity itself, and others just by getting more exposure to the greater volume of transportation.

And an often overlooked corporate structure that certain energy companies are entitled to use helps raise capital to fuel that growth... and provides better returns to shareholders.

We're talking about a master limited partnership ("MLP"), which is designed to be a tax-efficient entity to return capital to its shareholders.

MLPs are similar to real estate investment trusts ("REITs"). These are businesses with long-term asset bases and stable cash flows, and they're required to pay the majority of their earnings as tax-advantaged distributions to "unitholders."

Most energy companies have a section of their business that fit these criteria – specifically, transportation and storage.

In the case of pipelines, these are less connected to the price of oil. They instead collect money based on usage, which tends to be tied to energy demand rather than prices.

An MLP is a tax-efficient way to generate growth capital and lock in stable returns for investors. Many oil and gas companies chose to spin out the "midstream" transportation and storage parts of their businesses during this prosperous period and form MLPs.

Unfortunately, many of these MLPs took on too much short-term debt that they couldn't pay off in 2008, so they had to be folded back into their parent companies.

In the years following the recession, energy companies and MLPs had to reassess just how "safe" and stable the energy transportation business is.

Since 2014, one of the creators of the MLP space has dissolved the structure completely...

Kinder Morgan (KMI) first spun its pipeline business into an MLP in 1997. While it provided growth capital for a while, growth has slowed dramatically in more recent years. Furthermore, the costs and complexity of the structure began outweighing the benefits following the Great Recession – when the MLP business still had to pay out 90% of its earnings to investors.

The parent company consolidated the entire midstream business back in 2014 but has since maintained a strong dividend in an effort to provide investors with similar stability.

Kinder Morgan's yield (annual dividends divided by share price) has risen to 4.75%, which implies that the market views the dividend as risky.

For context, 10-year U.S. Treasury rates (often referred to as the "risk-free rate" because of the government's ability to pay its debt) are currently around 1.3%.

Higher risk requires a higher reward, which explains why Kinder Morgan's dividend yield is nearly four times higher than the risk-free rate.

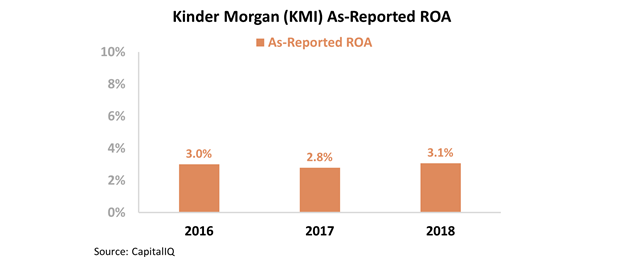

And when looking at the as-reported financial metrics, it's easy to see why investors think Kinder Morgan is risky...

Since 2016, the company has barely been profitable. Its return on assets ("ROA") has hovered around 3% – significantly below long-term corporate averages.

With these levels of profitability, investors are concerned that Kinder Morgan will have to direct its small amount of earnings to items like debt, interest payments, and capital expenditures. This puts the company's healthy dividend at risk.

However, the dividend is less risky than investors think...

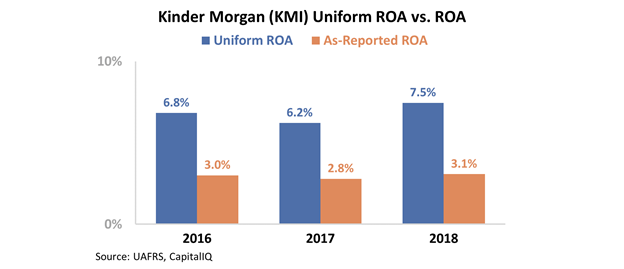

Using Uniform Accounting, we can see that Kinder Morgan is generating more than enough cash to continue servicing all of its obligations – including its dividend.

On a Uniform basis, the company's ROA is more than twice as strong... and it's improving. Returns ranged between 6% and 7% from 2016 to 2017, and they accelerated to nearly 8% in 2018. Take a look...

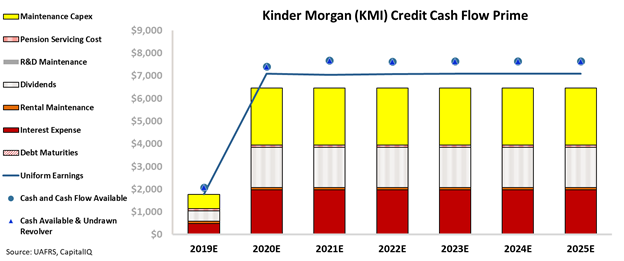

Furthermore, after cleaning up the company's cash flows for misleading line items like goodwill, excess cash, and one-time special items, we can compare Kinder Morgan's earnings to its annual obligations in what we call a Credit Cash Flow Prime ("CCFP") analysis.

Assuming the company is able to continue refinancing its debt thanks to its strong asset backing and stable ROA, our CCFP highlights that Kinder Morgan should be able to easily sustain its obligations, including its sizable dividend. Take a look...

It's no surprise that the market is pricing Kinder Morgan's dividend for high risk. With as-reported returns that are half as strong as the real numbers, investors misunderstand cash flows – thinking they're half as high. If that was the case, the company would likely need to cut its dividend to support its constant interest expenses and maintenance costs.

Uniform metrics show that Kinder Morgan is in a much more stable environment than investors realize. As a result, current dividend yields are likely too high considering the company's real risk.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

February 27, 2020

U.S. corporate credit profiles look healthy, but China may be a different story...

U.S. corporate credit profiles look healthy, but China may be a different story...