Dear reader,

Share buybacks are a battleground for politicians and economists alike.

Back in 1936, in the depths of the Great Depression, Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt claimed share buybacks could be a solution to income inequality.

His argument was that capital languished in corporations that paid lower taxes than investors, and so the federal government collected less tax money. Moreover, the capital returned could then be reinvested in more profitable businesses.

Today, many Democrats disagree... In February, presidential hopeful Sen. Bernie Sanders and Senate leader Chuck Schumer wrote a scathing New York Times opinion piece about how share buybacks lead to greater income inequality.

In a response to Schumer and Sanders, finance columnist Jason Zweig argued that a business can most effectively spend excess capital by buying back stock because investors can then invest these funds in businesses that have more opportunities for growth.

It's a controversial topic. So today, let's look at how buybacks work...

A share buyback is a transaction whereby a company purchases its stock from investors in the open market. Businesses typically buy back their shares because they believe that their stocks are undervalued. And because debt is typically cheaper than equity, financing share buybacks through debt will lower a company's cost of capital – meaning its projects have a lower hurdle to cross.

For much of the 20th century, buybacks were illegal. But in 1982, a U.S Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC") ruling created a legal process for share repurchases. Today, buybacks are a widespread practice... and they recently surged to new levels.

Under President Donald Trump's new tax plan, share buybacks reached a record high in 2018... and fueled further debate over the practice. Sen. Elizabeth Warren called share buybacks "a sugar high for the corporations," saying a company's stock price is unaffected in the long term by share buybacks.

While the common valuation metric of earnings per share ("EPS") will improve after a share buyback, the actual value of the business doesn't change.

While companies say they buy back shares because they believe their stocks are undervalued, many folks observe that businesses are notoriously bad at buying back their shares when they actually are undervalued.

From 2008 to 2017, industrial conglomerate General Electric (GE) spent $53.9 billion to repurchase its shares at an average price of $26... Today, shares are trading near $11. As we said last month, tech giant IBM (IBM) has repurchased a massive $200 billion in stock since 1995... and has consistently underperformed the market.

Some detractors of share repurchases will go so far to argue that the current stock market is entirely supported by large-scale buybacks. They say that when management teams repurchase shares, they're neglecting investment in research and development ("R&D") or infrastructure.

Here at Altimetry, we use share buybacks as an indicator for management's willingness to invest in growth because the practice can be viewed as an indication of the investment opportunities.

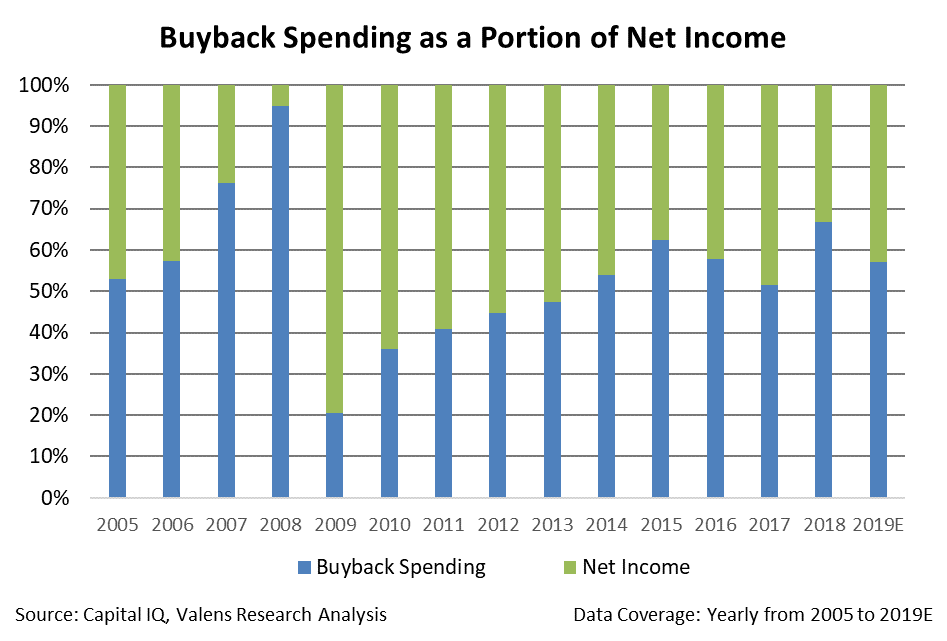

If a company's share buybacks increase significantly, then management may be out of places to put its funds. As you can see below, this is what happened in 2007 and 2008...

In 2008, share buybacks as a percentage of net income reached peaks of 97%, as the economy reached pre-recession highs. Since 2009, the percentage of buyback spending to net income mostly increased until 2015.

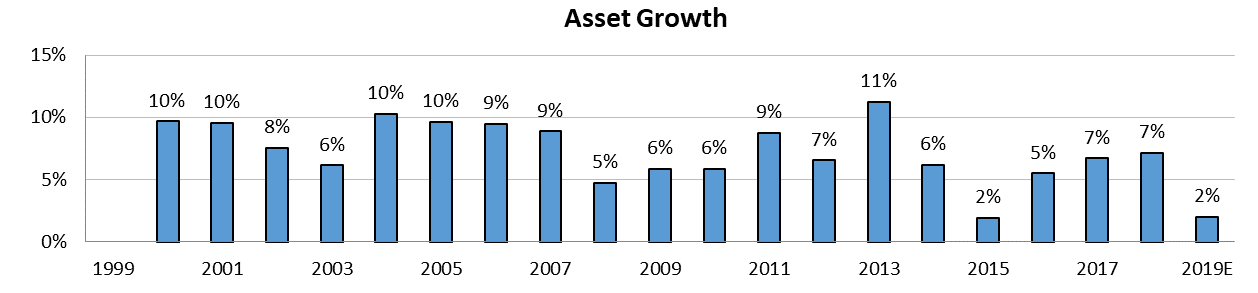

However, by 2017, share buybacks as a percentage of net income had declined, as management teams were increasingly willing to invest in growth. That showed up in our Uniform Accounting analytics on adjusted asset growth, which ran higher from 2016 to 2018.

As we mentioned, there was a step up in share buybacks in 2018... But this surge was because of cash repatriation related to corporate tax reform.

So far in 2019, share buybacks are higher than they were in 2017 as a percentage of net income... but are still down from highs in 2015, when we saw very low Uniform asset growth.

Overall, corporate management willingness to invest in growth appears more limited than in 2016 and 2017. But investment opportunities are not nearly as low as they appeared to be in 2007 – the last time we were preparing for a recession.

The debate over whether buybacks are good for investors and the economy will continue to rage as the U.S. moves further into election season. There will always be those who say buybacks are a tool of returning capital to shareholders and those who proclaim the practice is corporate waste.

No matter which view is true, buyback levels are a useful indicator for growth and opportunities to invest. And that indicator shows no reason to have concerns about a material negative inflection in growth that could signal more challenging times for the economy.

Regards,

Joel Litman

November 11, 2019