Last month, we discussed 'Oil Major' ExxonMobil (XOM) from a credit perspective...

Last month, we discussed 'Oil Major' ExxonMobil (XOM) from a credit perspective...

We explained how credit-ratings agency Moody's (MCO) gave Exxon an investment-grade rating despite some huge risk issues. Exxon has weak cash flows, a large dividend, significant debt maturities, and sizeable capital expenditures ("capex"). As we said...

Exxon is currently trapped between credit and equity investors. If management cuts the dividend, equity investors will hit the "sell" button. Meanwhile, if Exxon limits its capex, this restricts its ability to find future oil reserves. Credit investors are concerned with the company's ability to generate steady cash flows to pay them back.

These claims ruffled some feathers...

Altimetry Daily Authority reader James felt our comments about Exxon were an attack on fossil fuels overall. To clarify, we were leveraging public data on fossil fuels to put Exxon's liquidity struggles into context.

And the data show the facts – the ratings agencies are lagging in their analysis of Exxon's credit position.

At the end of the article, we asked readers for thoughts on other industries that might be impaired. Clearly thinking about the rest of the oil and gas marketplace, Christine from Alberta asked very simply: "What about pipeline companies?"

Pipeline companies are a unique part of the energy market...

Pipeline companies are a unique part of the energy market...

Some companies focus on long-term transportation, while others focus on the shorter range. It's important to understand where a pipeline company falls in order understand its commodity exposure. This means the bottom line is affected by changes in the price of oil or natural gas.

Distribution companies generally have more commodity risk. Their revenues are closely tied to energy prices... so they benefit when prices go up and get hit when prices go down.

On the other hand, transportation companies tend to be less exposed to price swings. They're often called "toll takers" or "toll roads" for the energy sector, because they just collect a payment for letting the commodity travel in their pipelines.

It's also important to look at a company's geographic position. Some firms operate geographic monopolies – they act as the only pipeline that can bring oil or gas into a market, or as the only propane distributor in a region. Others face stiff competition.

Within this sector, it's especially important to split up the industry when considering how many companies are lumped together simply as "pipelines."

Today, Williams Companies (WMB) is one of the largest pipeline businesses...

Today, Williams Companies (WMB) is one of the largest pipeline businesses...

Williams is an energy company that processes and transports natural gas over long distances.

In fact, only 7% of Williams' earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization ("EBITDA") is exposed to onshore oil. As a natural gas logistics company, demand mainly comes from the utilities sector – which makes up 68% of Williams' total volume. This provides the company with stable cash flows and high visibility.

Stability is always a good sign for creditors. Additionally, Williams has lower regular and maintenance capex thanks to the long lives of pipelines. Its infrastructure is mostly simple pipes, and after initially being installed, the lives of these pipes are measured in decades. They require limited maintenance to keep them up to snuff.

Williams' business favorably compares to other areas of the pipelines business, like those in the natural gas gathering businesses. These companies need to adjust their assets frequently, as fields are continuously discovered and depleted.

Similarly, Williams has a better capex profile than distribution businesses that need fleets of trucks and storage container infrastructure.

These factors are part of why Williams' Credit Cash Flow Prime ("CCFP") signals that the company is a low credit risk, even though things look concerning at first glance...

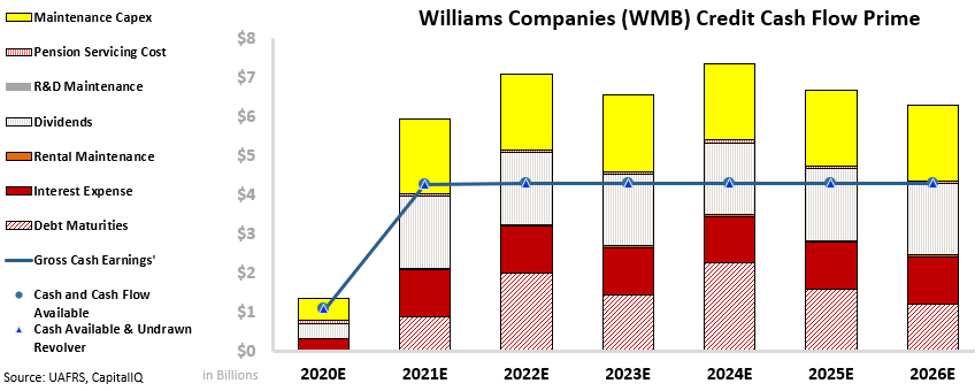

In the chart below, the stacked bars show Williams' obligations each year for the next five years. We compare this to the company's cash flow (blue line) and cash on hand at the beginning of each period (blue dots).

The bottom bars are the hardest for the company to "push off," and include costs such as debt maturities and interest expense. The higher bars are obligations that are more flexible, like maintenance capex and share buybacks.

Initially, Williams' CCFP doesn't look promising. Cash falls below obligations in every year going forward.

However, credit investors will look at the company differently. Creditors know how stable the cash flows are, so they'll be more willing to let Williams refinance its regular debt maturities.

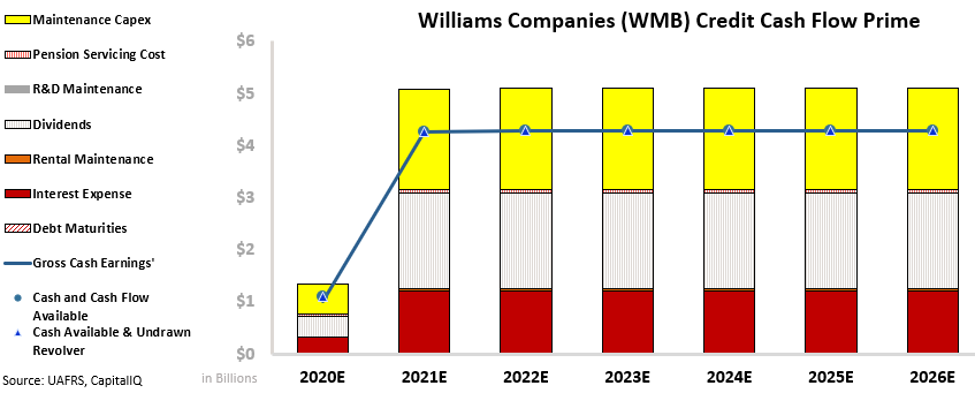

Therefore, Williams' CCFP should really look like this:

After removing debt maturities, we can see that Williams' cash flows exceed interest expense, dividends, and pension obligations.

And thanks to the low maintenance needed on its pipelines, we also know the company doesn't spend as much on maintenance capex as is necessarily budgeted.

So even though at first glance it looks like Williams might be suffering from a cash flow shortfall every year, we know that the company can actually manage this obligation easily.

It's no surprise that the company's cash flows would only exceed non-debt maturities and non-capex obligations. Williams only really needs to manage its cash flows relative to its interest expense and dividend obligations.

That's why it's critical to adjust how we look at Williams' CCFP... and that's why Christine's question was a great one.

While Exxon's dividends and credit are a concern, understanding this framework shows us that Williams is in much better shape.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

December 3, 2020