Next month, our friends at global asset manager Sprott are hosting an event with an impressive bench of attendees...

Next month, our friends at global asset manager Sprott are hosting an event with an impressive bench of attendees...

I may not be a gold bug, but I've been working with different members of the Sprott team for years. I've actually been on a program that Sprott Media hosts a few times... and I know event organizers Rick Rule and Albert Lu well.

I'm always impressed with the people Sprott can pull together for its annual natural resource conference. And this year, Rick and Albert have outdone themselves... even though they're hosting the event remotely due to the pandemic.

The conference lineup includes thought leaders like Jim Rickards and Steve Sjuggerud, as well as industry heavyweights like Randy Smallwood of Wheaton Precious Metals and Ross Beaty of both Pan American Silver and Equinox Gold.

If you're interested in the precious metals space, Sprott has the team you should listen to. I'll also be presenting at the event... though I won't be talking about gold and silver (I'll leave that to the experts).

It's a must-see event for precious metals investors. And you don't even have to travel all the way to Vancouver, Canada... the whole event is online. You can learn more about the conference, the cost, and how to register right here.

The turn of the 21st century was the era of the 'multinational'...

The turn of the 21st century was the era of the 'multinational'...

Some investors think of Coca-Cola (KO) or Disney (DIS) as creating international empires. But journalist Thomas Friedman had a different company in mind in 1996...

There are two superpowers in the world today... There's the United States and there's Moody's Bond Rating Service. The United States can destroy you by dropping bombs, and Moody's can destroy you by downgrading your bonds.

Friedman had a point... but the domination of the credit-ratings agency wouldn't last. The 2008 financial crisis brought to light a lot of the issues around the way ratings agencies like Moody's (MCO) do business.

There's a glaring conflict of interest between the ratings agencies and the corporations they cover. The three major ratings players – Moody's, Fitch, and S&P Global (SPGI) – all offer nearly identical services, so they compete with one another for corporate clients by offering the best "quality."

Therefore, the companies whose bonds are being issued can simply leave and pay a different agency for a better rating. Rather than accurate ratings, companies pay the agencies for what they want to see.

But the Great Recession exposed this issue when a number of supposed "investment grade" securities were eventually downgraded to high-yield "junk" territory after the market had already collapsed.

This conflict of interest is driven by a phenomenon we here at Altimetry call "incentives dictating behavior." In other words, people do what they're paid to do!

For its first 70 years of operation, Moody's actively avoided conflicts of interest because it refused to accept a dime from corporations.

Founder John Moody understood that his product was a corporation's rating... so his customers – that company's potential investors – wouldn't get any value from his service if he was misaligned with their interests. Unfortunately, starting in the 1970s – more than a decade after John Moody's death – his company and the other agencies began to charge the corporations rather than the investors for ratings... and thus their priorities changed.

But in the decades after that change, Moody's did well with the new model... until the ratings fiasco of the Great Recession.

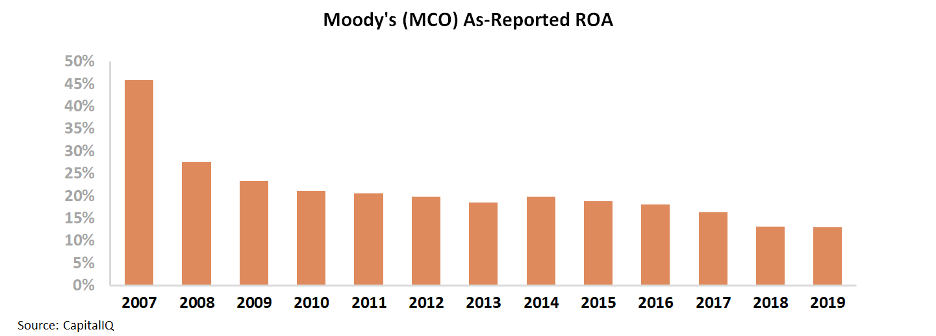

As you can see in the chart below, the company's as-reported return on assets ("ROA") has collapsed since then. In 2007, Moody's ROA peaked at 46%. Last year, it was only 13%.

It seems that both the bond issuers and investors have caught on to the flaw in Moody's business practice and aren't willing to pay a premium anymore. Rather than investors paying for data, analysts pay nothing for ratings... and much less for reports than companies do to get rated.

So does this decline in returns mean that Moody's will shift its priorities back to a model that aligns its incentives with paying investors and thus see investors start to pay a premium again?

It's unlikely. Moody's doesn't need to change, because the as-reported metrics misrepresent the company's true performance.

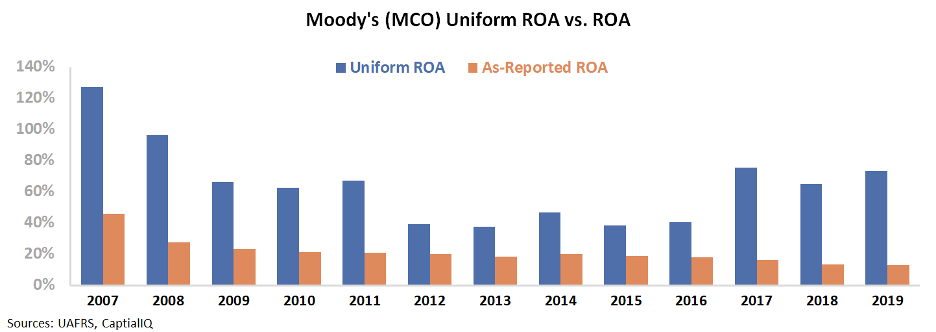

When we remove the accounting "noise" and look at Moody's real financials, we see that the company has bounced back well from the aftermath of Great Recession. Its Uniform ROA has been trending higher since 2012 – from 40% that year to 74% in 2019. Take a look...

By simply looking at the as-reported numbers, it would be impossible to tell that Moody's has begun to return to previous profitability levels over the past three years.

This looks like a positive development for the company... but unfortunately, it does nothing to modify management's incentives.

If Moody's continues to profit from a business model where the bond issuer pays for the rating, then company management has no reason to change its strategy. Moody's will continue to give ratings that the paying companies want to see rather than a rating that has value for investors.

And while Moody's is making money now, the quality of its credit ratings hasn't changed. Profitability went into freefall in 2008 as Moody's was forced to reevaluate its ratings from investment grade to junk.

Investors in Moody's are open to significant downside risk... as the conditions for another ratings disaster haven't changed. And yet, without Uniform Accounting, it would be impossible to see this.

Regards,

Joel Litman

June 16, 2020

Next month, our friends at global asset manager Sprott are hosting an event with an impressive bench of attendees...

Next month, our friends at global asset manager Sprott are hosting an event with an impressive bench of attendees...