401(k) assets in the U.S. are an estimated $6.2 trillion...

401(k) assets in the U.S. are an estimated $6.2 trillion...

This is a massive market, but these accounts generally have very specific rules on what assets they're able to invest in. And in a potentially important shake-up, the U.S. Labor Department just added another asset class to that list: private equity.

Some people might be excited to gain access to an exclusive club that only accredited folks with significant wealth, institutions, pensions, endowments, and other "qualified investors" could get access to. But that doesn't mean the change will happen immediately...

One of the key hurdles to clear for private equity is how the sector will successfully offer 401(k) investors as-needed liquidity. Considering the liquidity of most assets 401(k) investors can access already, they'll likely be expecting this from private equity as well.

That being said, 401(k) assets – much like pension assets – might be a natural fit for private equity investments.

Here at Altimetry, one key concept we focus on is the importance of understanding asset allocation when deciding how to build a portfolio. It's not just about what stocks, bonds, or other assets you buy... It's about making sure you put the right amount in your assets.

Cash you need in the near term shouldn't be in equities – they're too volatile. But money you won't need for 10-plus years should always be in equities, because they're the highest-returning asset over any 10-year period that we've looked at in history.

For most people who are building their 401(k), they're more than 10 years from retirement. So a private-equity investment – which is just another form of an asset allocation – may be a perfect opportunity.

Accounting statements have many uses...

Accounting statements have many uses...

Outside of ensuring that companies are being ethical and honest with their money, accounting is used by many parties for completely different reasons.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC") uses accounting statements to prevent fraud. Executive teams use their accounting statements to benchmark their company's performance.

In an ideal world, you could look at a company's statements over time to understand how its performance has changed – and that could help management make better decisions.

Similarly, consultants should be able to use the statements to identify areas of weakness and how to fix them... and investment bankers should be able to use accounting to provide companies with access to capital markets and mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

One other group that obviously uses accounting statements is investors. For them, the potential uses are nearly endless...

Investors can conduct deep forensic work on a company by analyzing multiple years of its financials, and can use them to understand which business might be less expensive relative to its earnings or assets.

All of these groups use the accounting statements to gain insights, compare, contrast, and identify actionable outcomes. And often, they all do the things we listed above in one way: "benchmarking" a business versus its peers.

They'll look at performance, leverage, valuations, and accounting trends of a company versus similar firms to identify anomalies or opportunities, as well as reasons to engage management.

But as regular Altimetry Daily Authority readers know, if you're looking at the wrong data, you might come up with the wrong benchmarking conclusion or outcome.

The truth is that the as-reported accounting statements aren't built for management, bankers, or investors to do this benchmarking the way they'd want to.

This is a major issue the users of financial statements need to address to make sure they're gaining the right insights from the accounting statements.

One great example is a business we briefly mentioned in the March 27 Daily Authority: Middleby (MIDD).

The company is one half of the food-service equipment manufacturing market along with the highlight of that day's essay: Welbilt (WBT).

As we mentioned, Middleby has been one of our favorite companies for more than a decade. It has a long history of successful strategic acquisitions that have helped grow its market share in the industry.

Middleby's management has always focused on acquiring businesses that it can apply its own equivalent to the Danaher Business System ("DBS") strategy to. The system was created as a way to operationalize acquisition integration, thus making it efficient and nearly foolproof.

Although global conglomerate Danaher (DHR) helped codify that kind of framework, Middleby has its own version that has worked for years.

Middleby has consistently been able to boost its acquisitions' returns while also selling the acquired company's products through its pipeline to save costs.

That said, if Middleby tried acquiring a company that already had similar returns, it might not be able to do much to boost its returns... and that business might not be the best acquisition target.

Looking at Middleby's biggest competitor, Welbilt, the company appears to have similar returns already.

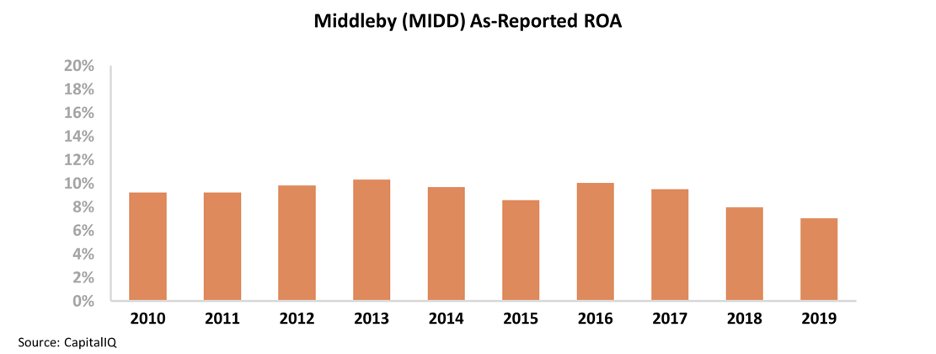

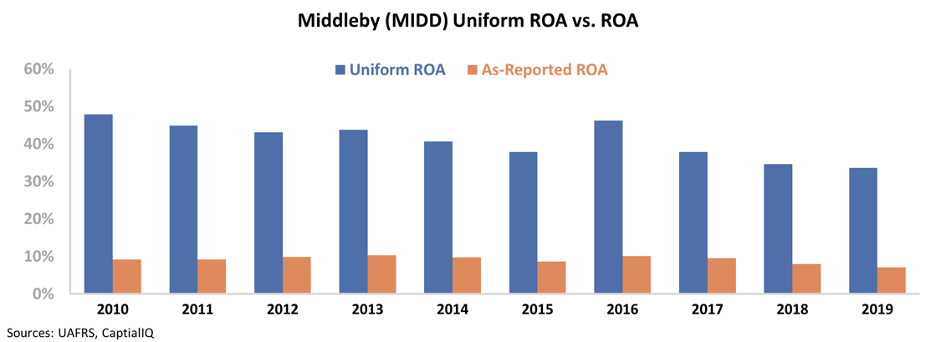

As we discussed in March, Welbilt's as-reported return on assets ("ROA") is near long-term corporate average levels of 6%. In 2019, Middleby's as-reported ROA was 7% – roughly in line with Welbilt's returns.

It makes sense for competitors to have similar returns if they're in a competitive industry.

That said, this is yet another case where the as-reported accounting statements fail to offer the real insights from a peer benchmarking exercise.

Instead, by using Uniform Accounting, we can see the right metrics investors need to see to make the right decisions.

As we said in March, Welbilt's Uniform ROA was 25% in 2019. And Uniform Accounting reveals an even bigger discrepancy for Middleby...

After adjusting for misleading line items like goodwill, operating leases, and research and development (R&D), we can see that Middleby's Uniform ROA was 34% last year – 5 times higher than the as-reported metrics would have you believe.

Furthermore, Middleby generated $3 billion in revenues last year with a $4 billion market cap compared to Welbilt's $1.5 billion revenue and $900 million market cap.

Part of the reason Welbilt is trading cheaper is due to the company's massive amount of debt. On an as-reported basis, it wouldn't make any sense for Middleby to acquire Welbilt. There's little chance Middleby could improve Welbilt's returns... and it would be taking on a large amount of debt.

That said, when you realize that Middleby could potentially boost Welbilt's profitability from 25% to 34%, and its larger size may make the debt easier to absorb, the value proposition becomes clearer.

We can see how this could be a potential deal only when using Uniform Accounting. This further shows that as-reported financials don't work as a one-size-fits-all solution for interpreting corporate profitability.

Regards,

Joel Litman

June 26, 2020