How long can the economy really last in a shutdown?

How long can the economy really last in a shutdown?

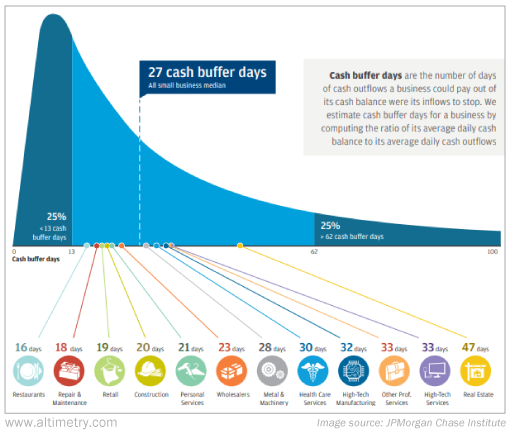

Earlier this week, I came across an interesting chart in an article from investment bank JPMorgan Chase (JPM). It was an analysis of the number of days of operating costs that small businesses of different types have in cash on hand to survive if there was no cash coming in – as is the case right now for many businesses. Take a look...

Many of the most "liquid" industries are, unsurprisingly, service industries with high margins or cash-rich tech companies. However, consumer discretionary names like restaurants and retail are the most at-risk.

This is a big reason why there has been such a concern about the economic impact of the current shutdown. The unfortunate reality is that many restaurants won't survive it.

Another interesting insight about this chart has to do with "excess cash."

Under Uniform Accounting, we remove any cash in excess of necessary operating cash from the balance sheet and instead give investors credit for it as a separate asset they own when buying a company's stock.

We do this because otherwise, companies like iPhone maker Apple (AAPL) would have artificially suppressed returns, and it makes it impossible to understand a company's real competitive moat.

Initially when we were researching the framework for adjustments like excess cash, we assumed that any cash in excess of 10% of revenue (i.e., around 30 days of cash) would be "excess cash." But interestingly, our statistical analysis of how much cash companies really do carry – and therefore a normal level that's necessary for operations – was much lower than we expected.

Our research found that the normal amount of operating cash – the level of cash that management would not operate without – was roughly 5% of revenue, or around 15 days. That lines up with the above graphic, which shows how rare it is for companies to operate with fewer days of cash on hand.

Earlier this week, we talked about corporate spinoffs and why investors like them...

Earlier this week, we talked about corporate spinoffs and why investors like them...

Spinoffs are a tax-free method of separating a business and rewarding investors in the process.

As a result, both the parent company and the spinoff tend to outperform the stock market, with a slight advantage to the spinoff.

However, in Wednesday's Altimetry Daily Authority, we used fast-food giant Yum Brands (YUM) and Yum China (YUMC) as an example that bucked the trend.

Specifically, Yum Brands had outperformed Yum China from the time of the spinoff to the beginning of this year (prior to the market downturn in the wake of the coronavirus outbreak).

As Uniform Accounting helped reveal, this was because Yum Brands was a fundamentally stronger business, despite the growth potential of the Chinese business.

The non-China business was able to boost profits by converting company-owned stores to a franchise model, similar to what McDonald's (MCD) has done over the last several years.

Despite the fact that the two companies essentially did the same thing, it was difficult to properly understand each company's financial performance.

There are many other examples where the spinoff company has little to do with the parent company, which can make this analysis even harder.

A great example of this is Welbilt (WBT), which spun off from Manitowoc (MTW) in 2016.

The only similarity between the two businesses is that they are both "manufacturers."

Manitowoc manufactures heavy industrial machinery, like the cranes you might see when a new skyscraper is being constructed. Welbilt, which was previously housed under Manitowoc, manufactures food-service equipment like commercial freezers and refrigerators, deli cases, and industrial ice makers.

As you can see, the scale is completely different.

It would be hard to consider these two companies similar to the way Yum Brands and Yum China are.

Because of this, Welbilt was a natural contender for a spinoff... But neither company has done particularly well since the transaction closed in March 2016.

Through the end of January, Welbilt had outperformed Manitowoc, up 9% versus down 11%. We're specifically stopping at the end of January because non-operating credit concerns for the business have sent the stock plummeting.

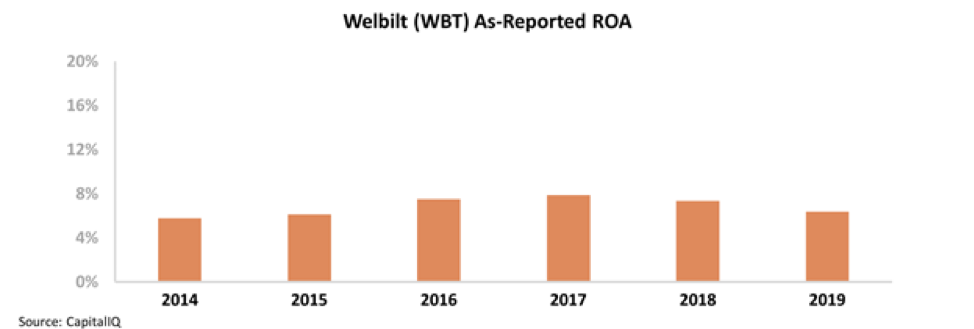

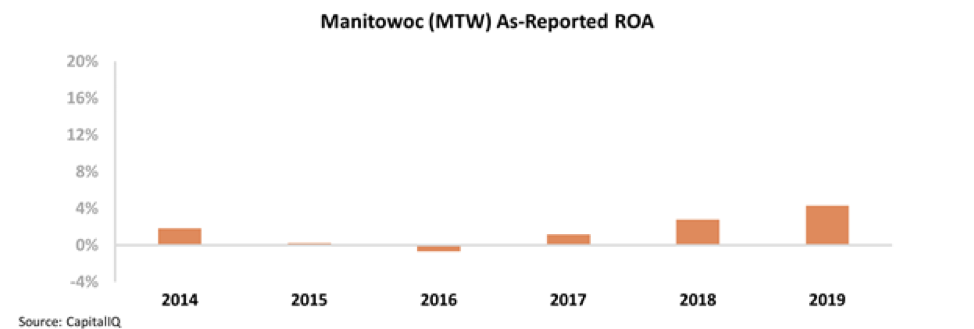

Looking at each company's financials, this performance makes sense. Since the spinoff, Welbilt has seen stable (albeit subpar) profitability. Over the past six years, its return on assets ("ROA") has hovered between 6% and 8%. Manitowoc has performed even worse, with its as-reported ROA dipping to negative levels in 2016 before recovering to a high of just 4% last year.

This seems to justify each company's stock performance since the spinoff. It also helps to justify the decision to split up the two companies given how different they are operationally.

However, the as-reported metrics fail to highlight just how profitable Welbilt is on its own.

You see, in addition to being a totally different business from Manitowoc, Welbilt also operates in a low-competition industry with one other major competitor: Middleby (MIDD), which has been one of our favorite companies for the last 10-plus years.

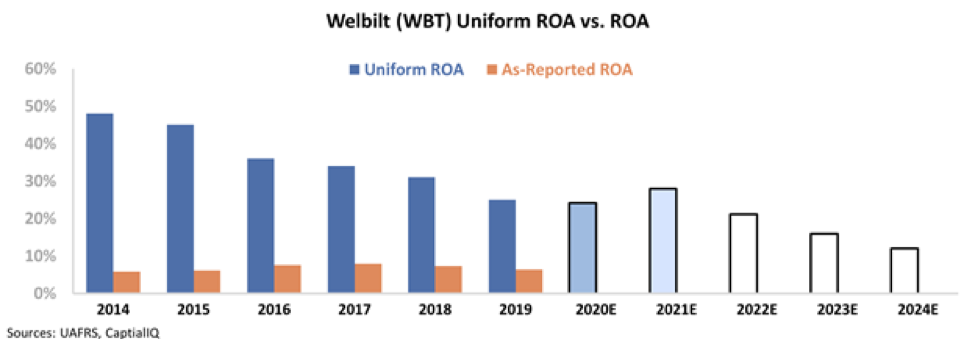

Together, Middleby and Welbilt have somewhat of a duopoly on the market. As-reported metrics fail to show that, but we can see it using Uniform Accounting.

Uniform metrics adjust for misleading accounting practices like the treatment of items like goodwill, operating leases, and research and development (R&D) on GAAP and IFRS accounting statements.

After making these adjustments, Welbilt starts to look like the profitable company it really is. The below chart highlights Welbilt's historical profitability (dark blue bars) compared with analyst estimates for the next two years (light blue bars) and what the market expects at current stock prices (white bars). Take a look...

Although Welbilt's Uniform ROA has fallen from all-time highs, it's still 25%, which is well above corporate averages.

At current valuations, the markets expect ROA to continue falling to historically low levels, likely because many investors are looking at the as-reported figures.

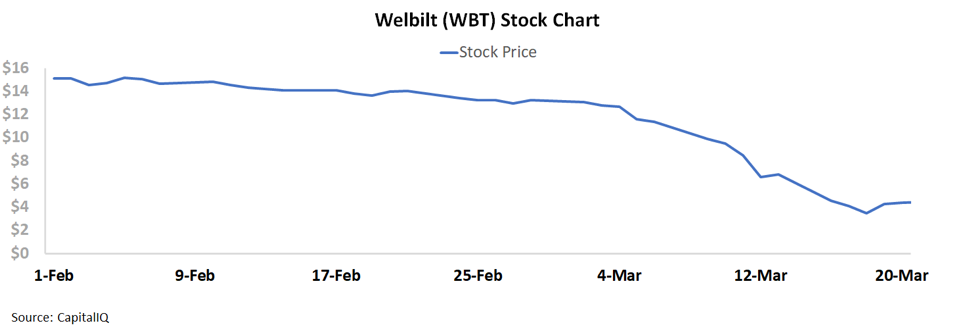

Earlier, we showed you how the stock had performed through the end of January. As you can see in the following chart, since February the stock has fallen 70%...

Some of the bearish view for Welbilt may be due to recent struggles in the restaurant industry. Welbilt is a supplier to the industry, and the coronavirus pandemic is significantly disrupting its business, as restaurants across the U.S. (and the rest of the world) are either closed or limited to take-out only.

That, combined with the $1.4 billion in debt on Welbilt's balance sheet, has investors worried. But using Uniform Accounting, we can figure out whether there is real risk here. And what we see is that the market isn't just misunderstanding Welbilt's returns, but also its credit profile.

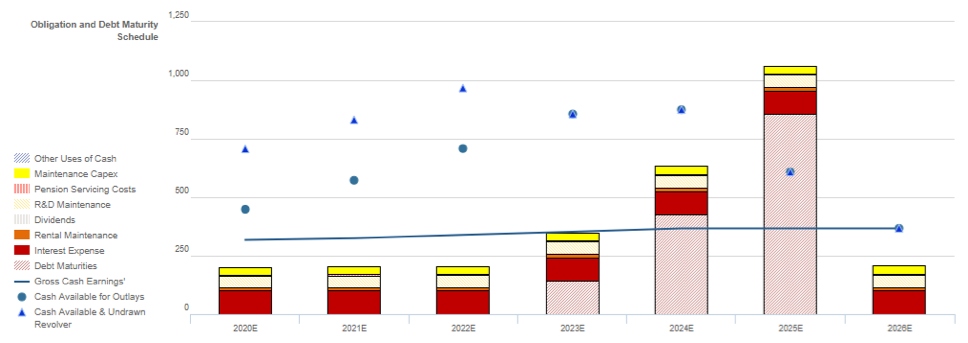

Longtime readers know we look at a company's credit profile in terms of not just how much debt a company owes, but when it owes it... And how its debt maturities and other obligations compare to the company's cash flows over coming years. We call this the company's "Credit Cash Flow Prime."

While investors are worried about Welbilt's massive debt load, we see a picture that is far less concerning:

Welbilt has considerable debt maturities, but the first debt maturity "headwall" isn't until 2023. Until then, the company just needs to worry about its operating obligations.

Assuming the company's revenue and cash flows dip significantly in 2020 because of the short-term coronavirus disruption, the company's cash on hand alone can cover its interest payments. Even excluding cash on hand, cash flow could fall in half and the company could still service almost all of this year's obligations.

The company's debt obligations and other obligations don't start exceeding normal operating cash flow levels until 2024. The market is overreacting by pricing Welbilt like an imminent default risk.

In this case, until investor irrationality in the midst of this outbreak, the classic spinoff investment strategy seems like it worked well.

Once investors stop panicking about the debt and start realizing just how profitable this business is – and that it's likely to survive – the stock will likely start to outperform its former parent company again.

Regards,

Joel Litman

March 27, 2020

How long can the economy really last in a shutdown?

How long can the economy really last in a shutdown?