A law of procrastination applies to the 'At-Home Revolution'...

A law of procrastination applies to the 'At-Home Revolution'...

We've all experienced this law by British naval historian C. Northcote Parkinson: "Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion."

Spoken in plain English, everyone procrastinates.

Parkinson originally wrote this law to talk about the unique problems in attempting to streamline government bureaucracy. To quote playwright Oscar Wilde, "the bureaucracy is expanding to meet the needs of the expanding bureaucracy." As officials attempt to create positions to improve efficiency, they inevitably create more bloat in the government apparatus.

However, due to human nature when presented with a deadline, this maxim can also be applied to any organization. If a project needs to be done in an hour, that's when it will get done. Meanwhile, if someone has a month to do the same task, the project will rarely be submitted by the first week.

However, this law needs further amending as many jobs transition to working remotely. As The Economist highlighted earlier this month, the At-Home Revolution has taken away the ability for managers to look over any one worker's shoulder. America's employees have split into two camps to reflect the new working reality.

The Economist has dubbed the first of these groups "the Slackers." For employees not under the direct eye of the boss, they dawdle on tasks before submitting each just before the deadline. Parkinson's law is amended for them by The Economist as, "for the unconcerned, when unobserved, work shrinks to fill the time required."

Meanwhile, the other camp is "the Stakhanovites." These are the employees who want to avoid the perception of being a slacker at all costs, allowing work to eat into their recreational time. The term is borrowed from the Soviet Union, where it was used to describe particularly industrious workers. For the Stakhanovites, "work expands to fill all their waking hours."

Finally, for the concerned manager, it becomes a necessity to regularly check in with employees. This leads to booking a plethora of Zoom meetings, which eats into supervisors' own time. "In lockdown, Zoom expands to fill all of the manager's available time."

Organizations will need to continue adapting to meet the unique challenges of remote work. Managers will need to motivate and monitor the Slacker camp, while acknowledging the work of the Stakhanovites and not letting them burn out. Meanwhile, they will need to manage their own time around Zoom meetings.

The work from home world is unlikely to completely disappear after the pandemic. As such, those who learn to adapt and leverage new technology such as click-tracking software to monitor some workers, new managerial skills for managers to balance wanting to interface with their employees and colleagues with enabling them to be productive, and new ways to help workers balance work life and their personal lives will be essential.

Consumers love the 'illusion of choice'... even if they don't realize it.

Consumers love the 'illusion of choice'... even if they don't realize it.

This is a powerful phenomenon. It occurs when consumers think they're choosing between different brands... when in reality, the brands are owned by one parent company.

For example, when people book vacations online, they have a wide array of choices – including Hotels.com, Travelocity, Priceline, and Kayak. And then there are the search engines of Booking.com and Expedia, which are some of the biggest websites to look for hotels and airfare.

There appears to be a huge selection for customers to shop from and compare deals on. In reality, the previously mentioned websites are all owned by the two biggest online travel agencies: Booking Holdings (BKNG) and Expedia (EXPE).

In fact, 93% of all hotel booking fees are controlled by these two big players... despite the dozens of different options available.

Consumers thus have the illusion of choice in selecting between these brands, as they're under the impression they have the ability to "shop around" and find that screaming deal.

The travel booking sector is just one example of an oligopolized industry, while still appearing to customers like a diverse set of businesses. By doing so, customers remain satisfied with their options... while Booking Holdings and Expedia are able to take larger margins.

Another industry where illusion of choice is a factor is in advertising. Massive brands such as McCann Worldgroup, FCB, Grey, and Wunderman Thompson all fall under the umbrellas of Interpublic Group of Companies (IPG) and WPP (WPP).

Like the travel industry, clients are given the false appearance of choice between agencies, creating a sense of satisfaction when they decide which advertising firm to go with – which agency "captures their vision."

In reality, these big conglomerates own more than 90 business across the advertising spectrum, giving them huge scale to capture client business. The massive portfolio of brands means these firms are like a blackjack casino, where the house always wins.

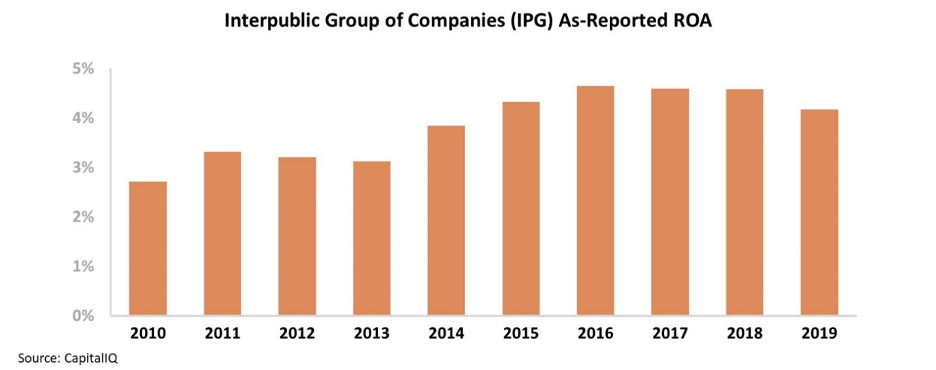

However, despite these massive advantages, Interpublic looks like a business that has generated returns on assets ("ROAs") that are barely above the cost of capital. Take a look at returns since 2010...

For Interpublic, returns between 3% and 5% are damning. A company operating as a strong oligopoly seeing so little profit must mean that management is failing to take advantage of some opportunity.

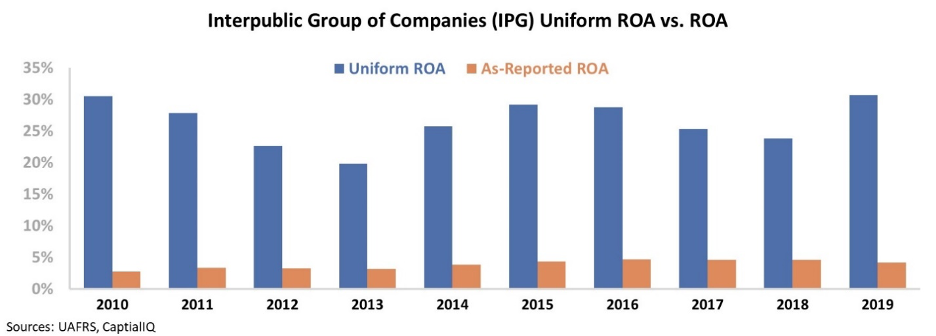

However, this picture of Interpublic's performance is inaccurate – it's pulled down by distortions in as-reported accounting. Due to the GAAP treatment of goodwill, the market has missed the mark on Interpublic's success.

The company has managed to successfully create an advertising conglomerate, generating high returns through presenting options to customers choosing between a variety of branding selections.

In reality, Interpublic's Uniform ROA has fluctuated between 20% and 31% since 2010. These are robust returns to match a company locking in the value of its powerful market position.

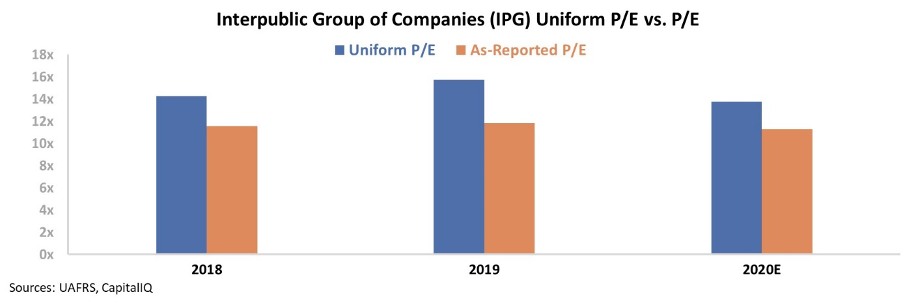

Yet, while Interpublic is generating higher returns, it's still being priced like a low-return business. Over an entire economic cycle, a high-ROA advertising business should be priced above the corporate-average price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 20. However, Interpublic is currently trading at a ratio of only roughly 15 times.

Ultimately, Uniform Accounting shows the true strength of Interpublic's business and the returns generated when customers are given the illusion of choice.

By creating the appearance of competition, customers are satisfied, and Interpublic is able to generate revenue regardless of what brand the customer chooses.

Once the market realizes that the advertising world's competitive environment is just yet another marketing ploy for clients and not economic reality, Interpublic's unique strength and competitive advantages should mean upside ahead for its stock.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

August 4, 2020

P.S. What's the best example of the illusion of choice you've seen in your daily life, where people think they have options but really have none? Give us your story by e-mailing us at [email protected].

A law of procrastination applies to the 'At-Home Revolution'...

A law of procrastination applies to the 'At-Home Revolution'...