Dear reader,

Earlier this year, we headlined our January report for our institutional investors: "A RECESSION IS COMING... in 18 months to two years if trends do not change before then."

Trends have changed significantly in the past nine months.

Many market strategists, financial journalists, and regular investors are calling for a recession by the end of 2019 or sometime in 2020.

A select few even suggested the recession has already started.

A few weeks back, we wrote about the real trigger for recessions. We mentioned that there's no chance for a recession without a credit crunch caused by borrowers who are stuck with debt they can't refinance or retire.

We said to keep your eyes on 2021, when U.S. companies' obligations begin to exceed their cash flows.

But now, we have good news. We're moving our expected timeline for the next recession. We now believe there is even more life left in the current economic cycle.

While the U.S. has a big debt headwall coming in 2021, that can change when U.S. corporations refinance their debt.

That wasn't happening last year or earlier this year... but it's exactly what we've been seeing recently. And it's been speeding up in the past few weeks.

There's a simple reason we're seeing a renewed interest in refinancing...

After rising massively in 2018, the costs for corporations to borrow have fallen.

We look at the credit default swap ("CDS") as a good proxy for how much it costs corporations to borrow. A CDS is a contract that acts like insurance for bonds. If a company can't pay its debts, a CDS ensures that the owner of the debt gets paid.

Much like health and property insurance, the higher the risk, the more expensive it is to insure. As such, in times of elevated credit risk, a CDS skyrockets in price.

Leading up to the Great Recession, the value of the CDS market ballooned to more than $62 trillion. Much like trying to purchase insurance midway through a car collision, it became impossible to buy reasonably priced CDS...

The "price" of a CDS roughly matches the cost of a company to borrow, above the cost for the U.S. government to borrow – the risk-free rate ("RFR"). If we add together the risk-free rate and a company's CDS, we can understand how much the all-in cost is for a company to borrow money. And if we add up that number for all the companies that have CDSs, we can understand how much it costs in aggregate for corporations to borrow.

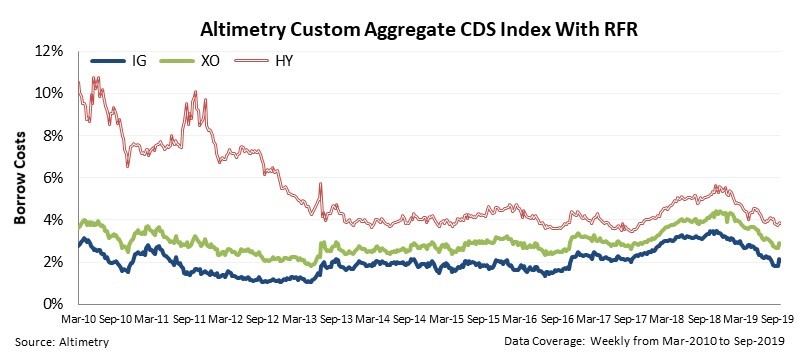

The chart below highlights CDS prices plus the RFR over the last decade. CDSs are broken into three buckets: investment grade ("IG"), crossover ("XO"), and high yield ("HY").

IG companies are the largest, safest, and most stable public companies, while HY companies are the smallest and riskiest. So it makes sense that HY CDSs are always more expensive than IG ones, and XO CDSs are always in the middle.

As you can see, the cost to borrow for all types of credit is significantly lower than it was in 2010, as we were coming out of the Great Recession.

Companies used those lower costs to consistently refinance their debt maturities. It made sense. When companies "roll out" their debt this way, they get to delay repaying it and see interest expenses decline or, at worst, stay flat.

Then in 2018, something changed. The refinancing market dried up. Companies weren't as active refinancing their debts. The cost for them to do so had risen significantly...

First, the Federal Reserve was actively hiking interest rates, with four rate increases in 2018.

And the underlying CDSs for corporate borrowers were rising too, as perceptions grew that the bull market was running out of steam. The cost to borrow for IG companies rose from around 2% to 3.5% in 2018 through early 2019. The cost to borrow for HY businesses jumped from 3.5% to 5.5%.

Companies saw these interest-rate increases and paused their refinancings. That's how the debt-maturity headwall in 2021 got so big earlier this year.

But in recent months, we've seen a big inflection... which caused the refinancing market to return. It's why we think debt-maturity headwalls that had been looking material for 2021 are likely to be pushed out to 2022 and beyond.

Without those debt-maturity headwalls in 2021, there's no risk of a recession.

The rise in the cost to borrow in 2018 has completely reversed itself. Thanks to the Fed cutting rates and CDS levels moderating, the cost to borrow is roughly in line with what it was from 2014 through 2017, when the refinancing market was strong.

And that's not the end of the story...

Tomorrow, we'll detail how Uniform Accounting gives us an even stronger "all clear" signal... and points us to the highest-yielding opportunities that are far safer than Wall Street would have you believe. We'll have more details here tomorrow morning.

Regards,

Joel Litman

September 30, 2019

P.S. While I don't believe we're on the brink of a recession today, the next few months might be a sideways market... and in this environment, stock pickers are going to do well.

In my brand-new Altimetry's High Alpha newsletter, my team and I are focused on the best companies that can break from this sideways trend and outperform in the months ahead. You can learn more about our strategy – and a subscription to High Alpha – by clicking here.