Even private equity is starting to suffer from "short termism"...

Even private equity is starting to suffer from "short termism"...

On Monday, we talked about how the lack of private-equity activity in the mergers and acquisitions (M&A) market is part of the reason why we aren't concerned about overheating "animal spirits."

Not only is private equity not as aggressive with acquisitions – even with its mountain of assets – but a recent report by market research company Pitchbook highlights that the length of time a private-equity firm owns a company is also falling.

Holding periods for private-equity firms had risen steadily from the end of the Great Recession until 2014, to a peak of just over six years... but they've been trending lower since then. Now, the average holding period is less than five years.

While many investors talk about how the concentration on the short term is ruining public equity markets and that private equity long-term views are the answer, it appears that private equity is starting to trend in the same direction.

With these firms looking to churn companies more than ever, are they really offering any incremental value beyond what public equity markets do, aside from their inherent leverage artificially boosting returns?

We've never written about a bank here in Altimetry Daily Authority...

We've never written about a bank here in Altimetry Daily Authority...

As regular readers know, our research is based on the concept of Uniform Accounting. These metrics provide financial data that are actually useful to investors.

One of the biggest differences between Uniform Accounting and traditional GAAP and IFRS accounting methods – and a reason this method is called "Uniform" – is comparability.

The rules behind GAAP and IFRS have changed dramatically over time, and they can vary across countries and industries. For example, you might not be able to properly compare a tech startup from the U.S. with a mature oil company headquartered in England using as-reported accounting.

However, the same two companies could be easily compared under Uniform Accounting. This is one of the main advantages of using Uniform metrics, but it doesn't work the same way with banks.

Regular readers will notice that we focus heavily on return on assets ("ROA") as a critical profitability metric. This is because most companies invest in assets as a way to generate money.

On the other hand, banks don't profit on "assets" in the same way other industries do. You see, banks make money by lending money. This is the inverse of all other companies – banks' liabilities are really their assets. For most companies, interest expense is a financing expense... but for banks, it's an operating expense.

Even with Uniform Accounting, it's not possible to provide comparability between banks and other industries. On top of that, banks can't be accurately measured by ROA... They instead need to be measured based on their return on equity ("ROE").

Interestingly, there's another group of companies similarly impacted by a strange and arbitrary accounting rule...

Asset management firms, who invest on behalf of their clients, are required to list their customers' assets on their balance sheets as both assets and liabilities.

But this doesn't make sense for asset managers, as they don't have control over their customers' assets in the same way a bank might.

As a result of this misplaced requirement, asset managers appear to have much larger balance sheets than are accurate – comprised of a combination of the company's "operating" assets and a large portion of "non-operating" customer assets.

So today, let's take a look at an example of how misleading this accounting rule can be for asset managers...

Federated Investors (FII) is an asset manager that focuses on offering a variety of mutual fund products, and currently manages more than $500 billion in customer assets.

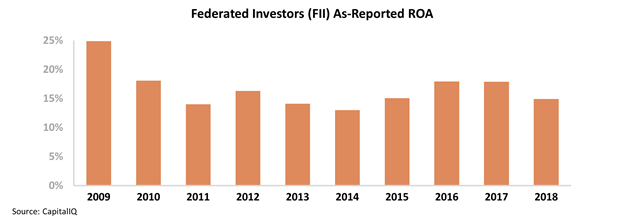

When looking at traditional ROA for an asset manager like Federated Investors, the company appears to be a cyclical, yet overall middling business with near-average returns. Since 2009, Federated Investors' as-reported ROA has ranged from 13% to 25%, most recently declining from 18% in 2017 to 15% in 2018. Take a look...

These returns aren't bad... but they're not indicative of the returns asset managers are able to generate. As we mentioned above, for these companies, as-reported ROA is based on a combination of both operating and non-operating assets, which makes their returns look much lower than they actually are.

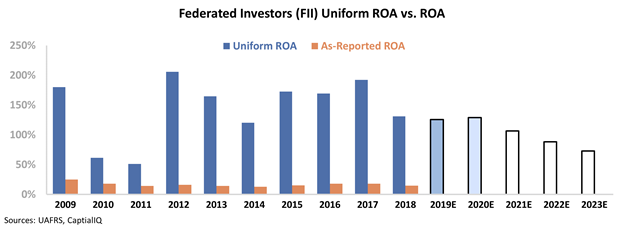

Once we adjust Federated Investors' financials under the Uniform Accounting framework – adjusting to remove non-operating assets from ROA – we can see that the company is far more profitable than the market realizes... and that investors may be too bearish on the company's future.

The chart below highlights Federated Investors' historical corporate performance levels in terms of ROA (dark blue bars) versus what sell-side analysts think the company is going to do for 2019 and 2020 (light blue bars) and what the market is pricing in at current valuations (white bars).

Despite some special factors related to building a fortress balance sheet that caused the company's Uniform ROA to fall to 50% levels in 2010 and 2011, Federated Investors is normally a 100%-plus ROA business. While still cyclical, we can see that the company's returns on its operating asset base are nearly 10 times higher than as-reported metrics show, every year...

Additionally, Wall Street analysts project that Federated Investors should be able to maintain these levels of profitability going forward. But investors are likely too focused on lower as-reported figures... and expect to see the company's ROA cut in half over the next five years to levels not seen since the fallout from the Great Recession.

Even with significant competition from exchange-traded funds ("ETFs") and low-cost index funds, these expectations seem unreasonably bearish for Federated Investors.

This is just one example of the many arbitrary accounting rules that impair the world of financial analysis. And as you can see with Federated Investors, the differences between as-reported and Uniform metrics can be massive.

Regards,

Joel Litman

January 29, 2020

Even private equity is starting to suffer from "short termism"...

Even private equity is starting to suffer from "short termism"...