A picture is worth a thousand words...

A picture is worth a thousand words...

In the February 10 Altimetry Daily Authority, we highlighted a website that we often direct our MBA students to when they're trying to understand why we talk about "quantitative non-financial metrics" or performance indicators ("KPIs").

Trefis is a powerful tool to understand how KPIs drive financial performance, partly due to how it helps users visualize how everything flows together.

Here at Altimetry, we spend a lot of time thinking about how to create charts that help distill complex ideas into digestible insights – whether they're just as simple as how wrong as-reported metrics are, or explaining how excessively high or low market expectations are for corporate performance.

We've heard a lot of talk recently about which companies are going to most benefit from ramping up diagnostic tests for coronavirus as we look to reopen the U.S. economy. And one of these is medical-devices giant Abbott Laboratories (ABT).

Trefis has a helpful breakdown of how to think about the potential effects of coronavirus testing on Abbott's performance, and how the company's other businesses are performing in 2020.

Much of the site's technology is paywalled... but plenty of these type of models are still accessible for free. As investors look for ways to position themselves for profits from the economy reopening, Trefis is a helpful tool to set expectations.

In the world of opulent luxury, four letters stand above the rest...

In the world of opulent luxury, four letters stand above the rest...

I'm talking about LVMH.

The Paris-based firm is the model success story for any luxury business. As a company, it has been able to grow massively while still maintaining its powerful branding and quality. Many businesses around the world have attempted to follow in LVMH's footsteps... but failed due to the unique circumstances surrounding its formation.

LVMH was created in 1987 with the merger of two already established luxury brands, Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy. Since then, LVMH has continued to use its acquisition abilities and scale to bring value to its brands.

Rather than focus on one segment of the luxury market, LVMH has targeted a multitude of brands – from champagne to hard alcohol, fine wines, fashion accessories, and more. While it looks far afield for its products, it only acquires companies that tick off certain boxes.

LVMH follows a strategy like Warren Buffett does – acquiring successful companies with an established management team that are looking for additional liquidity rather than an exit. After acquiring a brand, LVMH will keep the existing structure and management and simply "roll up" the company into its ever-expanding portfolio.

This means that LVMH has a wide variety of products – all managed by successful teams – and a pooling of capital and marketing strategies. Over the past 33 years, LVMH has seen strong success – with consistent Uniform asset growth and a Uniform return on assets ("ROA") in excess of 15%. The company's stock has been a 10-bagger.

To build a luxury empire, a firm needs an eye for successful businesses, significant capital, and the ability to enforce quality across a portfolio, but many have struggled to recreate LVMH's success.

However, who better to start a new LVMH than an employee from LVMH itself?

In the early 2010s, Coach was looking for a way to stay competitive as a luxury brand in a modern world. In 2014, the New York-based company hired Victor Luis, a former LVMH employee, to turn around its brand. Luis embraced the LVMH strategy and sought to duplicate the same success, but in the U.S.

So in 2015, Luis purchased luxury shoe company Stuart Weitzman in order to expand the luxury portfolio and provide needed liquidity for a proven brand. In 2017, he did the same thing and purchased Kate Spade, another high-end accessory producer.

This expansion of the portfolio led Coach to change its name to Tapestry (TPR), to reflect a move beyond premium leather products.

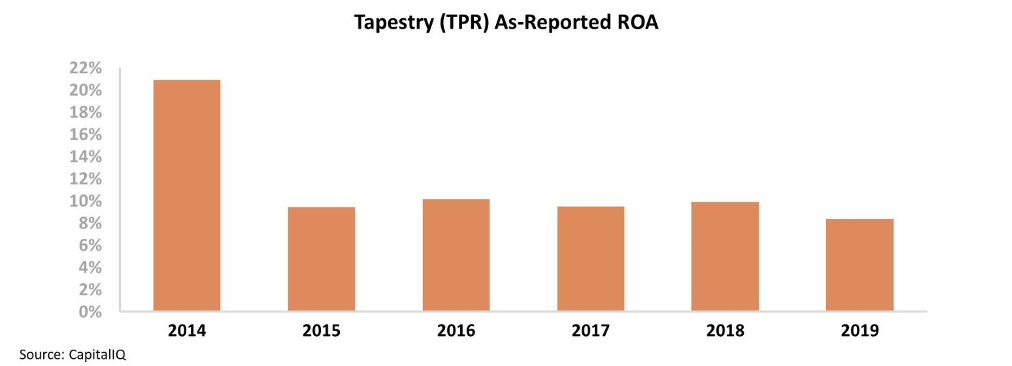

However, by using as-reported metrics, it appeared to the board that Luis' strategy to emulate LVMH was failing to produce any results. From 2014 to 2018, Coach's as-reported ROA fell from 20% to 9%, staying flat through Luis' tenure. Looking at these numbers, you could see why Tapestry's board let Luis go last year.

However, Tapestry management was making decisions using the "garbage in, garbage out" standard of as-reported accounting. Rather than a smart business move driven by numbers, Tapestry's board was blinded by wildly distorted metrics.

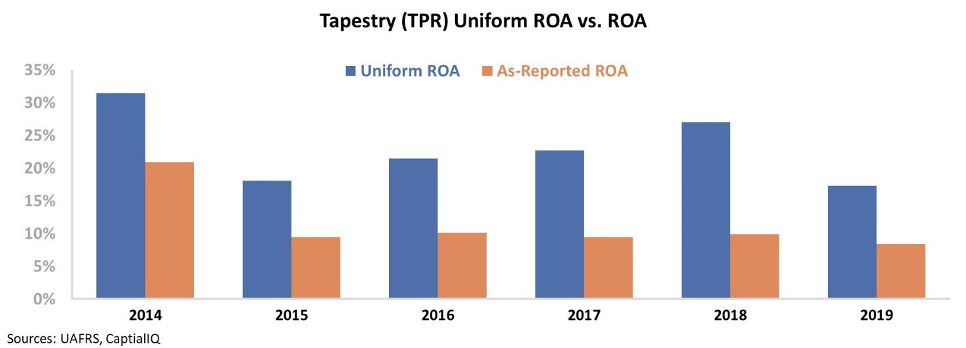

After making accounting adjustments to goodwill, stock option expenses, and other line items, we can see a different operating picture for Tapestry.

Rather than wasting shareholder money on frivolous expenses, Luis' strategy was working. As you can see below, after 2014, Tapestry's Uniform ROA began to rapidly expand year over year – from 18% in 2015 to 27% in 2018.

However, just as Luis began to integrate the acquisitions, the board let him go in 2019... and returns fell back to recent lows.

Due to using faulty metrics to make their decisions, Tapestry's board may have pulled the trigger too soon on firing Luis. It looks like LVMH's strategy was being realized, but an inability to measure this success means the U.S. will have to wait a while longer before seeing a domestic luxury conglomerate.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

May 14, 2020

A picture is worth a thousand words...

A picture is worth a thousand words...