Think about paper losses versus realized losses...

Think about paper losses versus realized losses...

There's a saying in the professional investing world – in particular among registered investment advisors ("RIAs") – when talking clients off a panic-driven ledge: "You don't actually lose any money in the stock market until you realize your losses by selling."

The only people who actually lost money in the Great Recession were the ones who sold at the bottom. If you held onto your investments, it certainly wasn't fun, but you made all your money back by 2013 and have made a lot more since then... just by leaving your money in the market.

Earlier this month, Orion Portfolio Solutions wrote a great (and short) piece explaining the difference in performance for investors who sold at the bottom of prior epidemic-driven pullbacks.

The table on market performance after outbreaks will look familiar to regular readers... it's similar to one that we published in the March 2 Altimetry Daily Authority about the market returns after prior pullbacks.

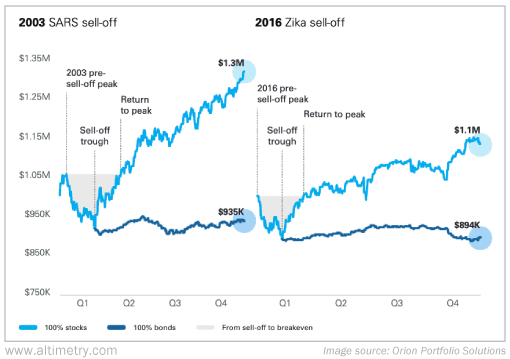

The chart below from the article shows the return for investors after one year if they panic sold at the bottom of a crisis and moved from stocks into bonds. As you can see, they would have been left very disappointed at the end of a year...

It's important to remember that at points of maximum panic, inaction can sometimes be the best approach when it comes to the market. Panic selling for losses is called "capitulation" for a reason...

Few services are as simple as being a 'middleman'...

Few services are as simple as being a 'middleman'...

"Distribution" is a business model that crops up in many industries. Listening to a distributor explain what it does is often hearing an overcomplication to justify its existence... At the end of the day, a distributor is just a "middleman" for a transaction between a producer and a buyer.

To be fair, this does offer some value to both parties. Sellers don't always want to go direct-to-consumer ("DTC") because it's costly to build out sales networks, there's no certainty of demand, and it can present logistical issues.

Meanwhile, from a buyer's perspective, distributors sometimes offer better pricing (they're able to buy in bulk from the seller), and it can be easier to do business with the distributor.

Just as important for both buyers and sellers, sometimes supply and demand can't be matched by production. By holding units, a distributor offers to match supply and demand when these get out of sync.

There are clear advantages to the model... but distributors essentially buy products, hold them until somebody else needs them, and then sell them. Even though some offer "value add" services like bundling, special pricing, or faster delivery, it's a commodity service.

And because they sell another company's products, distributors tend to have thin margins and little wiggle room for costs.

As a result, distribution isn't a wildly profitable industry – most of these businesses only make average returns.

Today's company is no different – its main business is to buy technology and software from the leading tech firms and distribute them to health care companies, government agencies, educational facilities, and other businesses.

Insight Enterprises (NSIT) got its start in 1988 as a mail-order computer-storage business and has grown into one of the largest tech vendors in the world. But despite the company's wild success and growth, it's still a distribution firm.

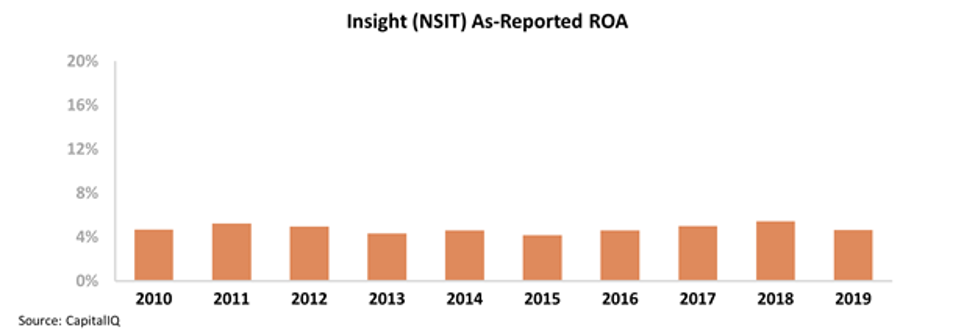

Based on our discussion about the business model, it may not come as a surprise to learn that Insight's return on assets ("ROA") is fairly low, and it has been for the last decade. Take a look...

Insight's returns have been fairly stable since 2010... but have only ranged between 4% and 5% – slightly below long-term corporate averages of 6%.

At these levels, it looks like Insight is a classic example of a commodity distribution business.

That said, it's not completely fair to write the company off that easily...

You see, because it's been able to grow into one of the largest distributors in the world, it has been able to supplement its standard offerings with a number of value-add services.

Insight provides its customers with consulting and managed services, thus helping its clients pick the best technology and software for their needs. It also offers ongoing technical support, transformation advisory, and product lifecycle monitoring.

While the as-reported financials make it look like these additional services aren't adding value to the company's bottom line, there may be more to the story...

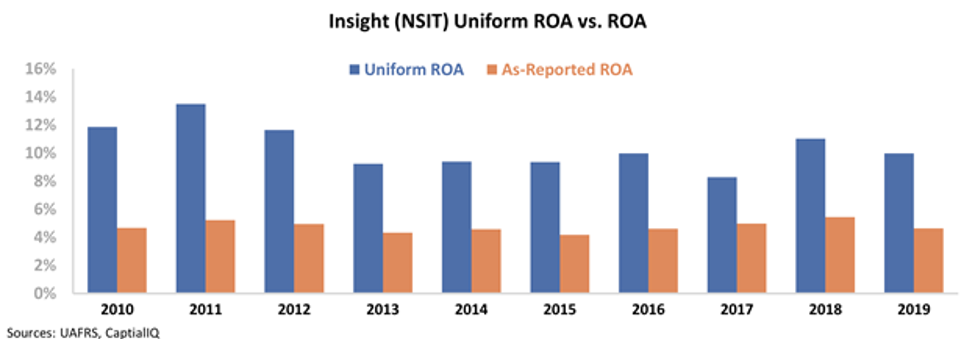

When we apply Uniform Accounting to Insight's financial statements, we get a more accurate report of its performance metrics.

Traditional accounting statements mistreat several line items on Insight's balance sheet and income statement which can make the company look less profitable than it really is. After adjusting for items like goodwill, accounts payable, and non-cash stock option expenses, we can see that Insight's ROA is roughly twice the as-reported values.

As you can see below, in 2019 alone, the company's Uniform ROA was 10% compared to its as-reported ROA of 5%. This shows that the company's value-add consulting and advisory services are contributing significantly to profitability.

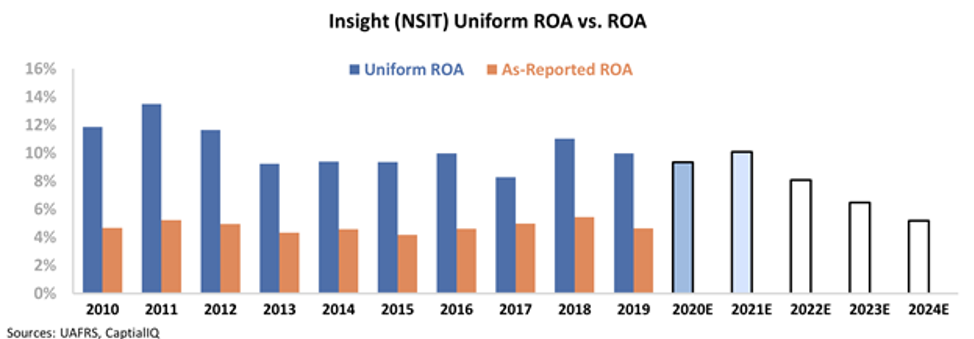

Furthermore, after making the correct adjustments, we can see what level of performance the market expects from Insight in the future at current stock prices.

The next chart highlights Insight's historical performance in terms of Uniform ROA (dark blue bars) compared to analyst estimates for the next two years (light blue bars) and investor expectations at current prices (white bars).

As you can see, the market hasn't realized how profitable Insight really is. Investors expect the company's ROA to collapse to 5% – far lower than it has been in the last decade.

Instead, this reflects that the market is paying too much attention to the as-reported figures for Insight.

As more investors start to understand the company's true profitability, we can expect to see valuations start to rise.

Regards,

Joel Litman

April 1, 2020

Think about paper losses versus realized losses...

Think about paper losses versus realized losses...