Who loses half his money on advertising? Apparently, everyone does...

Who loses half his money on advertising? Apparently, everyone does...

I recently had a great debate with a reader over the origins of a favorite quote of mine:

Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted, and the trouble is I don't know which half.

It's attributed to two giants of advertising across the pond from each other.

William Lever, First Viscount Leverhulme – the founder what's now consumer-products giant Unilever (UL) – was British. He was a viscount, after all. The other is John Wanamaker, a U.S. department-store magnate and marketing pioneer.

I love the debate... and I suppose who you side with somewhat depends on whether you favor the British or American advertising industry.

In the end, I'm sticking with Lever as the source – primarily thanks to David Ogilvy, who's known as the "Father of Advertising." Ogilvy was a British ad executive and copywriter who stated in his 1963 book, Confessions of an Advertising Man:

As Lord Leverhulme (and John Wanamaker after him) complained, "Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted, and the trouble is I don't know which half."

Given Ogilvy's reputation, I went with his account... But I recognize the difficulty in sourcing this quote still remains relevant today.

If you have an alternative source or reference, please let me know! I enjoy discourse like this with Altimetry Daily Authority readers.

Institutional and individual clients have asked us before how we treat advertising expense. Quotes like this qualify how we think about advertising expense.

We capitalize research and development ("R&D") and don't capitalize advertising under Uniform Accounting. In other words, we treat R&D costs as part of the company's investment, while we treat advertising as merely an operational expense. There are many reasons why, but even accounting greats knew that attributing the value of advertising is challenging.

Even in the modern era of cost per click ("CPC"), cost per impression ("CPI"), and other digital advertising metrics, understanding attribution and the life of an advertising investment is one reason Uniform Accounting doesn't capitalize advertising expense.

Part of our analytical process is reevaluating a company's credit profile...

Part of our analytical process is reevaluating a company's credit profile...

We assess businesses using our Uniform metrics to come up with an adjusted credit rating, which can easily be compared to ratings given by the big credit agencies like Moody's, Fitch, and Standard & Poor's.

Regular Daily Authority readers are familiar with the discrepancies between the as-reported GAAP numbers and the real Uniform numbers... and this can lead to major distortions between credit analysts' ratings and our Uniform credit ratings.

We recently saw this with semiconductor firm Advanced Micro Devices (AMD). The company looks safe based on our adjusted credit score, with an investment-grade IG3+ Valens credit rating (equivalent to an "A1" rating from Moody's). Moody's gave the AMD a non-investment-grade "Ba2" rating.

We decided to take it a step further... Upon further research into other semiconductor companies, the rating agencies appear to almost systematically overstate the industry's credit risk.

Across the board, credit analysts cited the volatility in the semiconductor sector as a rationale for their credit ratings. While it's true that parts of the industry have volatile cycles, it feels overly simplistic to apply the same logic across an entire sector.

This is a great opportunity to unpack some common misconceptions about semiconductors... first and foremost, the idea that it's a homogenous industry.

AMD makes chips for computers – in particular, graphics-processing units ("GPUs"). We recently highlighted NXP Semiconductors (NXPI) as a leader in the Internet of Things ("IoT") space. In that same essay, we mentioned Qualcomm (QCOM), the world's leading manufacturer of phone chips.

In addition, there are numerous semiconductor firms making products specifically for solar companies, artificial intelligence, and usage in audio components.

To cite the same risk profile for all of these diverse end markets appears to oversimplify the industry.

To the same point, with semiconductor companies servicing so many markets, they must clearly have different product cycles. For instance, while computers might be nearing the end of a cycle, solar technology is still developing rapidly.

Nearly the entire semiconductor industry is viewed as if it's entering the end of a cycle, indicating a huge drop in profitability and major downside.

This presents an interesting opportunity to look at companies within the industry with much longer to go in their product cycles – companies like Analog Devices (ADI).

Without getting too technical, Analog Devices manufactures components used in technology in areas like health care, autos, and industrial equipment.

While not quite as fledgling as solar technology, these are end markets with a lot of growth remaining... and Analog Devices is a premier player in the market.

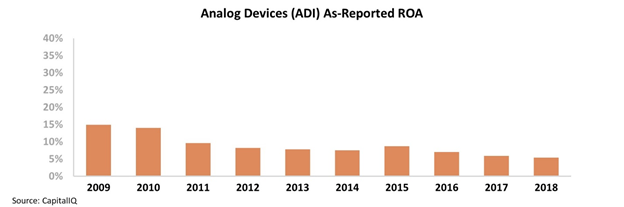

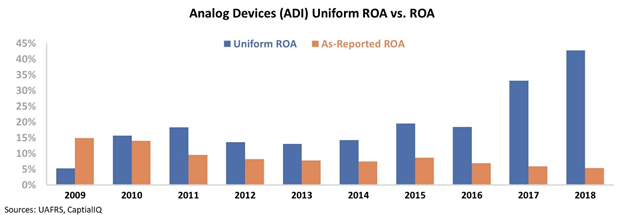

When looking at the company on an as-reported basis, it's clear why credit agencies and investors may be skittish – Analog Devices' return on assets ("ROA") has declined in nearly every year over the past decade...

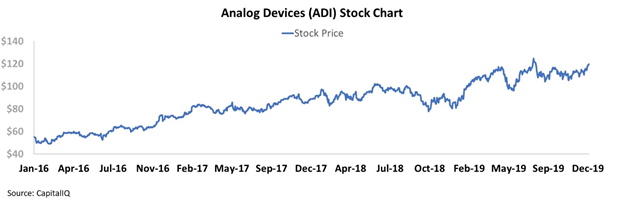

And yet as the company's profitability has reached decade lows, its stock has performed quite well – returning more than 100% since 2016. With declining returns and a rising stock price, Analog Devices may appear to be a screaming short primed for a drop ahead.

However, once we apply our Uniform Accounting framework – adjusting for accounting inconsistencies like the treatment of goodwill, capitalizing versus expensing R&D, and the impact of stock option expenses – we can see what the market has actually reacted to.

Not only is Analog Devices' ROA far higher, but it has expanded significantly from levels around 15% to more than 40% over the past few years...

At these levels, Analog Devices is clearly not in the same category as a generic computer chip manufacturer whose end markets may soon grind to a cycle low.

With the continued momentum for higher-tech solutions in health care, vehicles, and industrial equipment, the company very well may be able to maintain its recent ROA expansion.

On an as-reported basis, Analog Devices may appear to follow the same conventions as any other semiconductor firm. However, once we look at the company with a Uniform lens, we can see a prime example of the breadth of the semiconductor industry.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

December 27, 2019

Who loses half his money on advertising? Apparently, everyone does...

Who loses half his money on advertising? Apparently, everyone does...