It's the one ingredient needed for a long-term recession...

It's the one ingredient needed for a long-term recession...

Back in September, before anyone had heard of social distancing and when the news cycle was dominated by the trade war, we discussed the conditions for a recession. While the world has changed over the past 10 months, our position has not.

Major recessions are always caused by a sweeping inability to refinance credit, which leads to insolvency. Over the past 150 years, every major recession besides this one has begun with a debt crisis. If companies can refinance their debt, then any long-lasting contraction will be delayed. It's only when a firm is unable to borrow that a recession has a long-term effect on the economy.

When analyzing current market conditions, the large dip in the first half of 2020 was caused by an enforced demand strike, not a credit event. Companies were unable to pay their bills not because of credit drying up, but due to revenue constriction.

As firms continue to see revenue under pressure, securing credit becomes harder and harder. Fortunately, the U.S. government has pumped massive liquidity into the system in order to reduce the risk of a large-scale credit default event. So far, this has prevented the health crisis from spiraling into a credit crisis.

However, as the shutdowns and quarantines have continued, the runway to full economic recovery has extended as well. As Bloomberg reported earlier this month, this has finally started to catch up with some companies. More than 130 firms have declared bankruptcy due to coronavirus pressures.

Some of the names aren't entirely surprising. Many are large companies such as Hertz (HTZ) and J.C. Penney (JCP) that were already under pressure before the pandemic. The stay-at-home orders were simply the final nail in the coffin for the car-rental and brick-and-mortar retail giants.

Over the past two months, more companies have declared bankruptcy in industries exposed to the quarantine – such as oil and gas, retail, travel, and restaurants. This is the first indication the previous round of stimulus and paycheck protection loans, while sizable, haven't gone far enough to completely avoid the beginnings of a credit crisis in some areas of the market.

As the recovery continues, bankruptcies will be an incredibly important trend to watch. If further help isn't extended to firms unable to pay their bills, credit defaults could rise due to continued pressure to demand.

Clearly thus far, the two-speed recovery for those who are essential or can provide services to people at home versus those companies exposed to consumption outside the house is likely to continue. The important indicator will be if that contrast will lead to more companies going under, which could lead to a real credit-driven second wave of economic pressure.

If most U.S. businesses survive the pandemic, the economy could soon return to pre-virus operation. If defaults continue to rise, credit events could create a more sustained downturn... throwing off the potential economic recovery scenario we discussed yesterday.

Tell us your thoughts... What company that has closed or gone bankrupt since the pandemic were you the most surprised went under? Let us know at [email protected].

Railroads became one of the first U.S. stock market manias in the second half of the 19th century...

Railroads became one of the first U.S. stock market manias in the second half of the 19th century...

As economic growth boomed in the U.S. after the Civil War and the steam engine became viable to manufacture in large quantities, many companies tried to capitalize on this new opportunity.

Railways were going up all over the country. In the 1880s alone, total railway miles nearly doubled in the U.S. Financing for railroad companies also became increasingly easy to find. This led the firms to lay track anywhere, even if it was redundant or had little utility.

In their desire to gather capacity, railroad companies offered rebates, discounts, and priced below cost to try to fight for market share. Many ended up taking massive leverage to build tracks and stations.

Thanks to that easy credit, railroad companies were able to survive for decades even with their flawed business model...

However, everyone eventually realized that the entire U.S. couldn't become one giant railroad. And like bubbles always do, it finally burst when one of the biggest railroad companies in the country – the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad – wasn't able to pay its interest expense with the cash coming in from freight and passenger revenue. After the bankruptcy, many other railroads followed suit.

That led to the Panic of 1893. Unemployment skyrocketed into the teens and banks across the country failed.

It also began a great and prolonged railroad consolidation. The industry finally understood that for it to make any money, weak competitors would need to be removed.

This led to a wave of roughly 150 consolidations in the sector. By the middle of the 20th century, only a handful of companies controlled most of the railways across the country. By the 1990s, it got to the point where there were only four railroads that mattered in the U.S., and these companies continue to operate today.

Two main providers operate in the western U.S.: Union Pacific (UNP) and BNSF Railway, which is owned by Berkshire Hathaway (BRK-B). The other two are in the east: CSX (CSX) and Norfolk Southern (NSC).

Through this mass consolidation, railroads finally began to enact pricing power in the hopes of earning a decent profit.

This truly accelerated in the early 2000s as Union Pacific and BNSF Railway, having finished consolidating their final major acquisitions from the 1990s, started to be rational about both capital expenditures ("capex") and raising prices. This has allowed the rail companies to increase efficiency and decrease their operating ratio (operating expenses as a percentage of revenue).

On the other hand, the two major eastern railroad companies didn't rush to follow suit. In 2017, that changed for CSX when the company hired E. Hunter Harrison as its new CEO and started to focus on operating ratios. Even after Harrison passed away, this has been an increasing focus at CSX.

But for Norfolk Southern, based on as-reported metrics, the company looks like the stubborn last of the old breed of railroad.

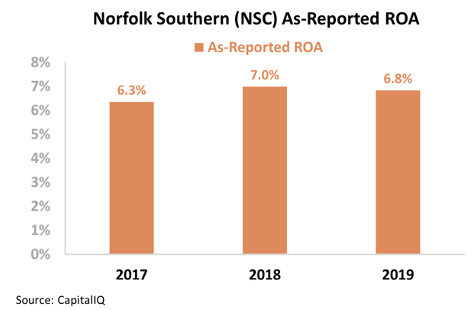

According to GAAP accounting, it looks like Norfolk Southern has tapped out its ability to improve operating efficiency. The firm's as-reported return on assets ("ROA") have floundered below corporate averages since 2017.

While looking at Norfolk Southern's as-reported numbers, investors understandably may be scratching their heads as to why the company is refusing to improve itself.

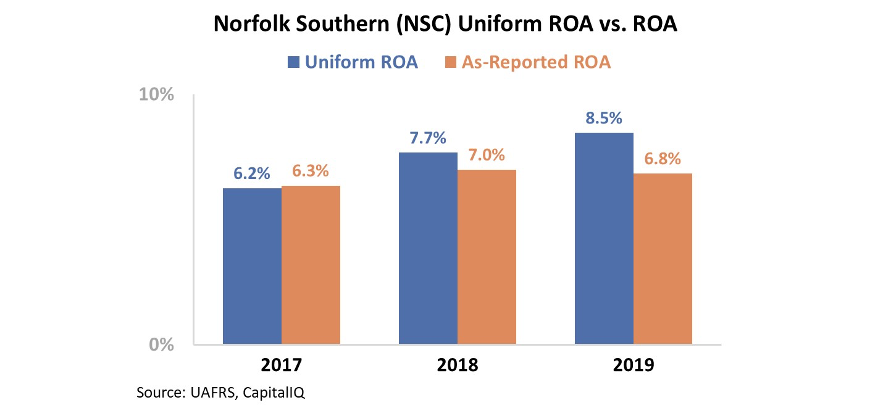

Unsurprisingly, the issue is that the as-reported numbers aren't showing the entire picture. Large distortions in interest expenses and capitalized operating leases make Norfolk Southern look less efficient and profitable than it actually is.

In reality, the company's Uniform ROA has steadily grown – reaching 20-year highs at nearly 9% in 2019. Take a look...

Looking at only as-reported metrics, it would seem as though Norfolk Southern is a struggling firm that could be even hit harder by a lack of trade due to the pandemic. It's no wonder then that Wall Street has written off a company in an industry that saw its glory days in the 19th century.

In reality, Norfolk Southern is following the steps of its peers and is seeing operational improvement. You just have to know to look at the right numbers.

Regards,

Joel Litman

July 28, 2020

It's the one ingredient needed for a long-term recession...

It's the one ingredient needed for a long-term recession...