The opposite of evolution is 100 years of financial statements...

The opposite of evolution is 100 years of financial statements...

As I write this, I'm preparing a speech this Saturday titled "Frontiers of Accounting."

I'm covering how the calculation of earnings has changed so dramatically over time.

In 1919, the annual report for automaker General Motors (GM) was just 19 pages long. I'm looking at it right now. The income statement page was typed in what would be something like 12-point font.

By 1940, GM's annual report expanded to 83 pages. To make more room, the income statement was typed in something smaller, similar to 10-point font.

Now, 100 years after that quick and clean 19-pager, GM's numbers force us to squint. I need reading glasses for what can only be tiny 6- or 7-point font. Despite squeezing in all that extra information per page, GM's report has still ballooned to more than 340 pages.

If GM had maintained the same font size and spacing as the 1919 financial statements, the current report would be more than 1,500 pages long.

The financials have evolved to seemingly unlimited details in getting to the same key elements of net income, assets, liabilities, and equity.

The rules governing financial statements and related disclosures have evolved to a near-incomprehensible level. Digging through all the numbers requires a significant amount of experience and massive time allotment.

The sponsor of the forum I'm presenting at this weekend is The Institute of Certified Management Accountants. Interestingly enough, the audience will largely be made up of corporate finance executives.

Management teams are just as interested in making sense of the financial statements they publish as the investors who have to read them. They don't set the accounting rules, they have to follow them along with everyone else, long as they may be.

It's incredible... We've gotten so far away from accounting shining a light on corporate performance that even the management teams themselves need to be educated on how to interpret the financials they're producing.

As the holiday season kicks into high gear, make sure to do your shopping (and shipping) early...

As the holiday season kicks into high gear, make sure to do your shopping (and shipping) early...

As you may or may not know, the U.S. has a trucking shortage. As more consumers continue to buy more on Amazon (AMZN) and less at their local shopping centers, demand for trucking is beginning to outpace supply.

Not only is it tough to find enough people willing to drive thousands of miles through the night, but the physical trucks themselves represent a bottleneck, too.

This is an issue that we study a lot. Whether you run a factory, own a hotel, or sell tickets for baseball games, your goal is to sell everything you produce – an idea called "maximum capacity."

Running near maximum capacity is a good problem to have. Shipping companies, truck makers, and even the companies that make truck parts are all aware that trucking is reaching capacity.

Moreover, demand for trucking is showing no sign of slowing down. This means that trucking companies will need to grow their fleets and hire more drivers.

While the initial investment may be expensive, it's good for all related parties. Parts makers sell more parts... truck makers sell more trucks... and transportation companies ship more stuff.

The end result is more drivers working, and consumers not having to worry about their packages arriving late.

At the end of this virtuous cycle, it also means the economy has grown.

As I mentioned above, every industry has some sort of measured capacity. All businesses measure capacity. In fact, the concept of "capacity utilization"(or actual output relative to potential output) can be measured for our entire economy.

When looking at capacity utilization for the entire nation, the same principles apply. High capacity utilization means companies will likely need to invest to grow capacity, while low or sharply declining utilization may lead to a pullback in growth.

Additionally, capacity utilization is related to inflation. The difference in actual output versus potential output represents the amount the economy can "grow" without actually investing. When utilization rates are exceptionally high – typically above 85% – companies need to invest to grow, which can cause inflation.

As part of our assessment of the economy and the potential for investment and earnings growth, we look at capacity utilization.

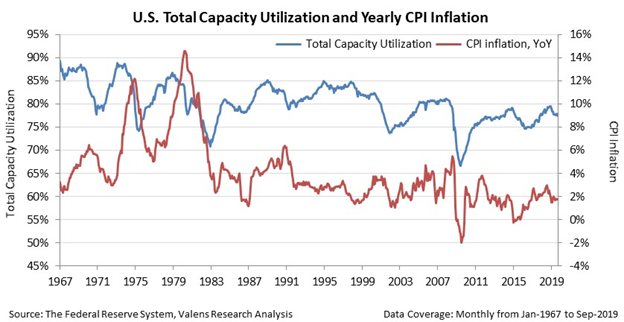

Below is a chart tracking total capacity utilization ("TCU") versus annual inflation in the U.S. As you can see, TCU has been ranging between 75% and 80% since the economy recovered from the Great Recession...

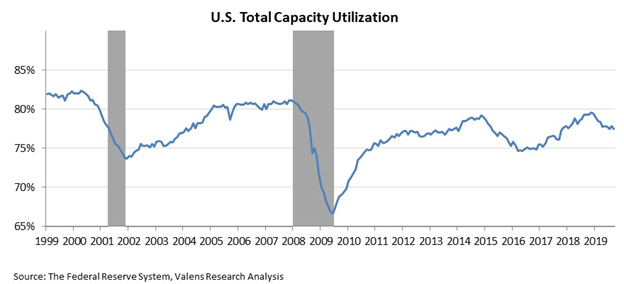

In the next chart, you can see that during the Great Recession, TCU fell to historically low levels on the back of severely reduced production levels. Subsequently, as utilization has recovered, it has risen back to the 75% to 80% range again. This is well below levels that would cause inflationary concerns, but high enough to signal that companies might still be investing.

Capacity utilization flirted with the high end of the range twice in the past 10 years: in 2014, just before the credit crisis in oil and gas... and in late 2018, after the impressive post-tax-break-fueled run in the economy.

As we highlighted in the September 6 Altimetry Daily Authority, during both of those periods, investment was trending up. Higher capacity utilization leads to stronger investment.

Specifically, the rise in capacity utilization in 2018 led to significant capital expenditure spending, just as one would expect.

Subsequently, this year, capacity utilization has tapered off. This has meant less urgency in investing, and therefore slower earnings growth. If this continues, we could continue to see subdued earnings growth.

But with the market starting to put issues with the U.S./China "trade war" in the rearview mirror, we're starting to see signals in earnings calls that management teams are getting more bullish, and that capacity utilization could start to tighten again.

Monitoring this key metric is hugely important to understanding investment and earnings growth. It can be a great signal for where the market is headed next.

Regards,

Joel Litman

December 9, 2019

The opposite of evolution is 100 years of financial statements...

The opposite of evolution is 100 years of financial statements...