The 'retail apocalypse' continues to take victims...

The 'retail apocalypse' continues to take victims...

In the December 26 Altimetry Daily Authority, we discussed how electronics retailer Best Buy (BBY) has survived the retail apocalypse in a way most companies have not. To compete with online retail, Best Buy offered price matching and focused on showrooms for product demos.

But many other businesses haven't been so lucky.

Last month, market-research firm CB Insights published a fascinating report highlighting 81 retailers that have gone bankrupt since 2015. Many were brands that people have forgotten... but others were ones we'd all remember – like electronics retailer RadioShack and department-store chain Sears.

It pays to remember that a bankruptcy filing doesn't have to be the end of a company's story. It certainly hasn't been in the airline industry... Many airlines went through bankruptcies repeatedly in the 2000s before emerging even stronger.

A Chapter 11 bankruptcy means a company is reorganizing instead of liquidating. We can continue to shop at some of these businesses without even realizing they're in that reorganization process... moving past their prior debt issues, or maybe even already having overcome those problems.

The ones that most surprised me on the CB Insights list were BCBG, PacSun, and Rue21. I remember analyzing PacSun when I was working at the hedge fund Abernathy. And my wife just bought some dresses from BCBG in the past few months.

You can see the full list right here. What one jumps out at you the most? Let us know at [email protected].

The rise of streaming has many people questioning the future of traditional cable TV and broadcasting...

The rise of streaming has many people questioning the future of traditional cable TV and broadcasting...

We're in the midst of the "streaming wars," and it's transforming how we consume media... and how many companies do business.

The astonishing success of media giant Disney's (DIS) Disney+ has shown that more than one streaming service can thrive. And with more than two months behind us since its launch, we can start analyzing the numbers.

Through the end of 2019, the service had more than 20 million subscribers. Wall Street analysts initially expected Disney+ to reach 13 million subscribers... by the end of 2020.

And now, streaming companies are showing they can compete with TV networks on content.

Last week, the Academy Awards released its nominee list. For the first time, a streaming company led the field. Netflix (NFLX) earned 24 nominations – one more than Disney and four more than Sony Pictures.

It's another blow to traditional media outlets, which are rapidly losing competitive advantage.

What's more, streaming platforms have showed that they can compete not only on recorded content, but also on live content.

Hulu, another streaming service owned by Disney, has been amassing a number of prominent live TV events, spanning from game show Jeopardy's "Greatest of All Time" tournament to the College Football National Championship game.

With this move, concerns about the future of traditional broadcasting companies are stronger than ever.

In contrast to the massive rise of streaming stocks like Netflix, the entire media industry has struggled in recent years – especially larger conglomerates with assets spanning from cable TV to print media.

Take today's company, for instance... Tegna (TGNA) is a broadcasting company with a series of television stations in its portfolio. For context, it's the largest owner of local CBS and NBC stations in the country. It's among the largest owners for stations affiliated with ABC.

Despite its strong position, over the past five years, Tegna's stock has been treading water, significantly underperforming the overall market. As you can see, shares are roughly flat since early 2015...

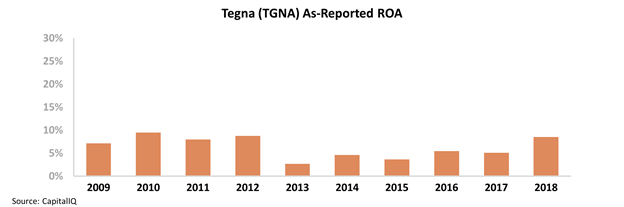

This seems to align with Tegna's recent levels of earning power when analyzed under as-reported GAAP metrics. Over the past decade, the company's as-reported return on assets ("ROA") has never reached 10%. Tegna's ROA has spent several years in the 3% to 5% range – below long-term corporate averages.

That said, there may be less to this connection than meets the eye...

Tegna is a smaller, more agile player in the media space when compared with many of the big media conglomerates. Thanks to its smaller size, it has been able to better adapt to the changing media environment.

Prior to 2015, Tegna was known as Gannett – and more closely resembled a typical media conglomerate. In addition to its broadcasting assets, Gannett owned printed assets like USA Today and a group of local newspapers.

Lo and behold, the economics of print media and television stations are quite different. By dividing up its assets by category, Gannett was able to split itself into two smaller, more flexible companies. It rebranded in 2015 – Gannett split off its print assets and took the original name (now trading under the ticker GCI), while the broadcast group rebranded itself as "Tegna."

The name was a partial anagram of Gannett. It was meant to symbolize the split between the "old" print media and the "new" broadcast media.

As-reported accounting fails to recognize the success of Tegna's focus on "new" media.

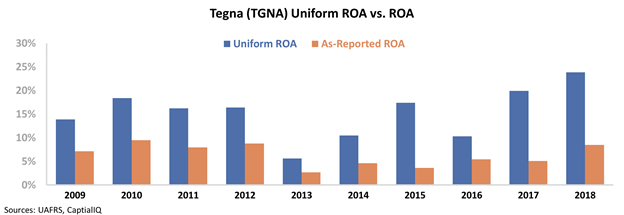

Of course, we apply Uniform Accounting to adjust for inconsistencies like the treatment of goodwill and terrible GAAP distortions in operating lease capitalization and expensing. Under our Uniform metrics, we can see that Tegna's new business model has actually been quite successful...

For the past decade, Tegna's Uniform ROA has consistently been higher than the as-reported numbers would suggest. Additionally, while Tegna's as-reported ROA only recently recovered to historical averages, we can see that in reality, its Uniform ROA has reached new peaks as the company has shifted its focus entirely toward its syndicated television stations. You can see the vast discrepancies below...

While certain segments of the media industry have justifiably come under pressure, not all media companies deserve the same concerns from investors. The real economic results – using Uniform metrics – separate the good from the bad.

Companies like Tegna, with its large focus on local television stations, may be in a separate category from large media conglomerates. This is another example of a signal that may be impossible to detect without the help of Uniform Accounting.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

January 22, 2020

The 'retail apocalypse' continues to take victims...

The 'retail apocalypse' continues to take victims...