The NBA is embracing disruption... and that's not a surprise.

The NBA is embracing disruption... and that's not a surprise.

The NBA All-Star Game last weekend was a major hit. A new format gave the game a competitive edge that hadn't existed in decades.

Many of the professional sports leagues in the U.S. are attempting to innovate in an effort to try to bring more interest to their all-star exhibitions.

In 2016, the NHL turned its all-star game into a smaller, four-team tournament. The NFL just recently changed the Pro Bowl rules to enable a bigger risk-reward opportunity for teams after a touchdown.

Even the MLB, as focused as it is in centuries old traditions, has played with changes in its all-star game format in recent years.

But none of these changes have created as much engagement as those of the NBA All-Star Game. And no other league has been as comfortable in exploring opportunities to completely re-invent itself in the midst of great success as the NBA has.

The league is also in discussions about creating a mid-year tournament and a "play in" tournament for the playoffs, among other major changes to how the season is designed.

While the NBA's innovation is impressive, basketball's willingness to disrupt itself isn't surprising when you look at the people behind the NBA...

As this PitchBook article highlights, many of the most influential NBA owners come from private equity and venture capital. These owners understand that putting the right people in place – and letting them innovate – is a powerful way to create value and build a lasting presence.

The focus these type of investors have brought to corporations through innovation and by building sustainable business models – either as investors or as threats to the companies themselves – has helped contribute to steadily rising corporate returns across the U.S.

This has also instilled a greater management commitment to capital efficiency and has increased focus on value-add business models. It's part of the reason why Uniform return on assets ("ROA") is at a historically high (but sustainably robust) level.

Don't be surprised if these owners turn their basketball teams into increasingly larger cash-generating machines.

Just yesterday, we mentioned a company driven to bankruptcy by input prices...

Just yesterday, we mentioned a company driven to bankruptcy by input prices...

We discussed some of the challenges with commodity businesses, and how price changes can lead to issues with long-term profitability. We explained that despite its impressive position as the largest dairy producer in the U.S., Dean Foods has felt the pressures of milk prices at 20-year lows and from increasing competition to traditional milk.

Not only were the company's operations under pressure from low prices, but Dean Foods had a large amount of debt coming due that it knew it couldn't pay.

As a result, the dairy giant filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in November.

Without knowing too much about bankruptcy code or law, it would be easy to assume that this is the end of the line for the producer of popular milk brands like TruMoo and DairyPure... and that Dean Foods suffered from the "kiss of death."

However, if you've recently visited a grocery store, you may have noticed that Dean Foods' products are still in the refrigerators. Given the short lifespan of dairy, there's no way that milk is left over from November.

This is because bankruptcy isn't the same thing as ceasing operations. As we mentioned, Dean Foods filed under Chapter 11 – this form of bankruptcy protection allows a firm to reorganize itself.

This way, the company is still up and running while it looks for a buyer to come in and save it. And in the case of Dean Foods, one was announced earlier this week... Agricultural cooperative Dairy Farmers of America is buying a substantial part of the business. And while Dean Foods waited for a buyer, it secured $850 million in funding that's specially designed for companies in distress.

Bankruptcy caused by a company not being able to refinance pending debt maturities is a fairly common type of bankruptcy, but it's far from the only one. Businesses go bankrupt for many reasons beyond standard debt restructuring.

In fact, some of the most prominent bankruptcies over the past 30 years have been due to factors other than a company holding too much debt.

For example, Delta Air Lines (DAL) went bankrupt in 2005 because it had accrued large amounts of pension obligations that it knew it would be unable to fulfill. In fact, the company had little risk with its bonds and bank debt at that time.

For a more recent example, California energy firm PG&E (PCG) filed for bankruptcy protection in early 2019. It had amassed large amounts of liabilities related to the 2018 California wildfires. Yet the company continued to operate, and it's still a profitable business today despite the growing wildfire obligations.

One of the most famous examples of this type of bankruptcy was in the late 1990s and early 2000s. At the time, we saw massive bankruptcies in the wake of the decades-long asbestos lawsuit process.

With more and more Americans developing respiratory illnesses related to asbestos exposure, the companies that used asbestos in their insulation materials had to build massive reserves on their balance sheets in order to meet liabilities for health issues.

The ads for mesothelioma that still run on TV today are a testimony to the impact of asbestos. And in total, more than 70 companies filed for bankruptcy related to the lawsuits.

Among the biggest names in the chain of dominoes was Owens Corning (OC). Even though it stopped using asbestos in its products by the late 1970s, lawsuits continued piling on for several decades. At one point, the company was facing over 84,000 individual lawsuits.

Owens Corning saw the writing on the wall... With most plaintiffs receiving millions of dollars in damages and a lawsuit quickly making its way to the Supreme Court, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2000. It was able to come back from bankruptcy by 2006 to address its more than $5 billion in asbestos claims.

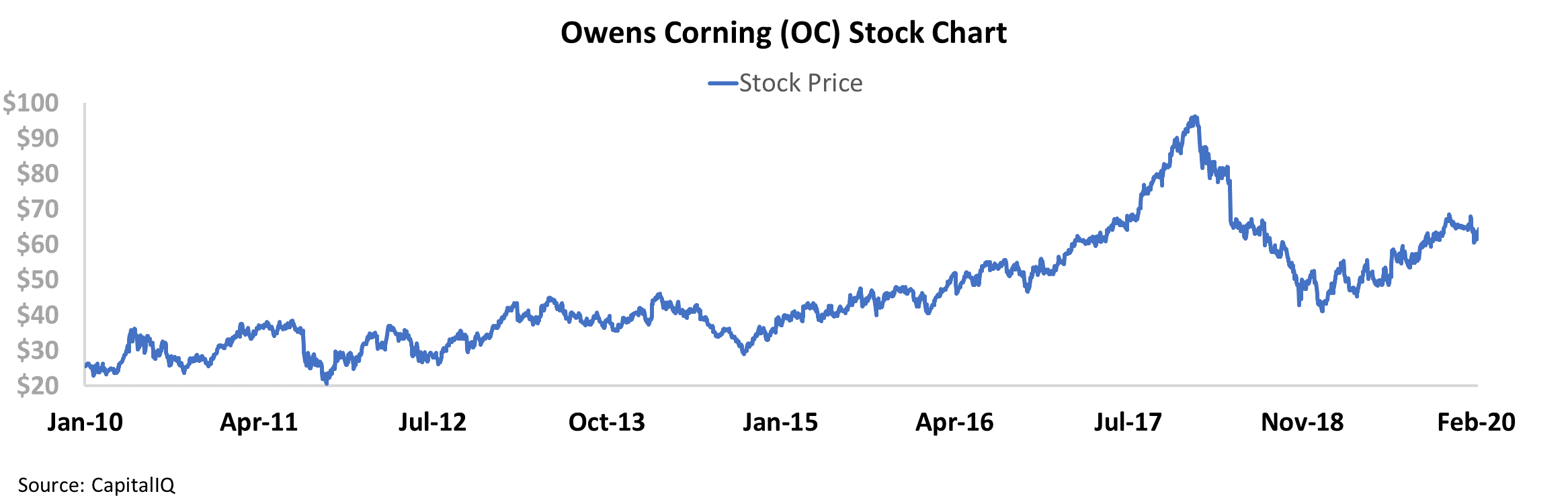

Since then, the stock has barely kept up with the market. As bankruptcy is such a serious concern, investors likely have a bad impression of Owens Corning.

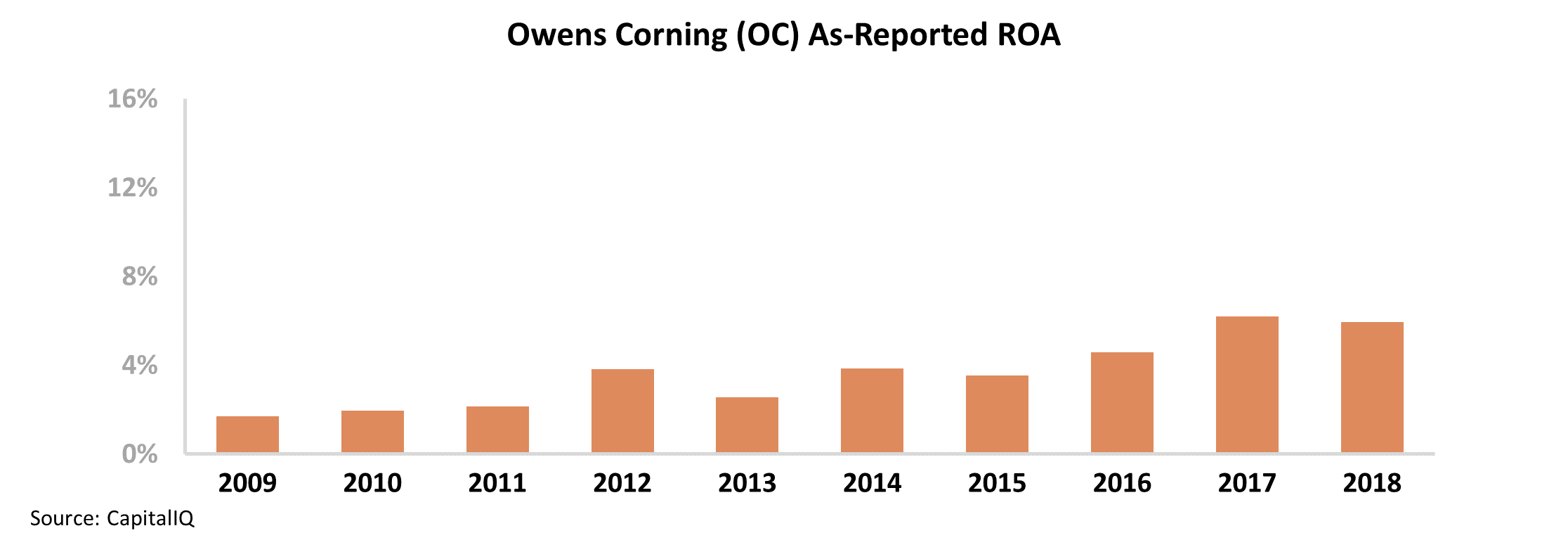

And when looking at the company's returns, investors appear to be justified. Coming out of the recession and its recent bankruptcy, Owens Corning has been able to slightly improve profitability – with its return on assets ("ROA") rising from 2% in 2009 to a peak of 6% in 2017.

Considering that the long-term corporate average ROA is 6%, Owens Corning's profitability is far from impressive... and it appears to justify the company's fairly weak stock returns.

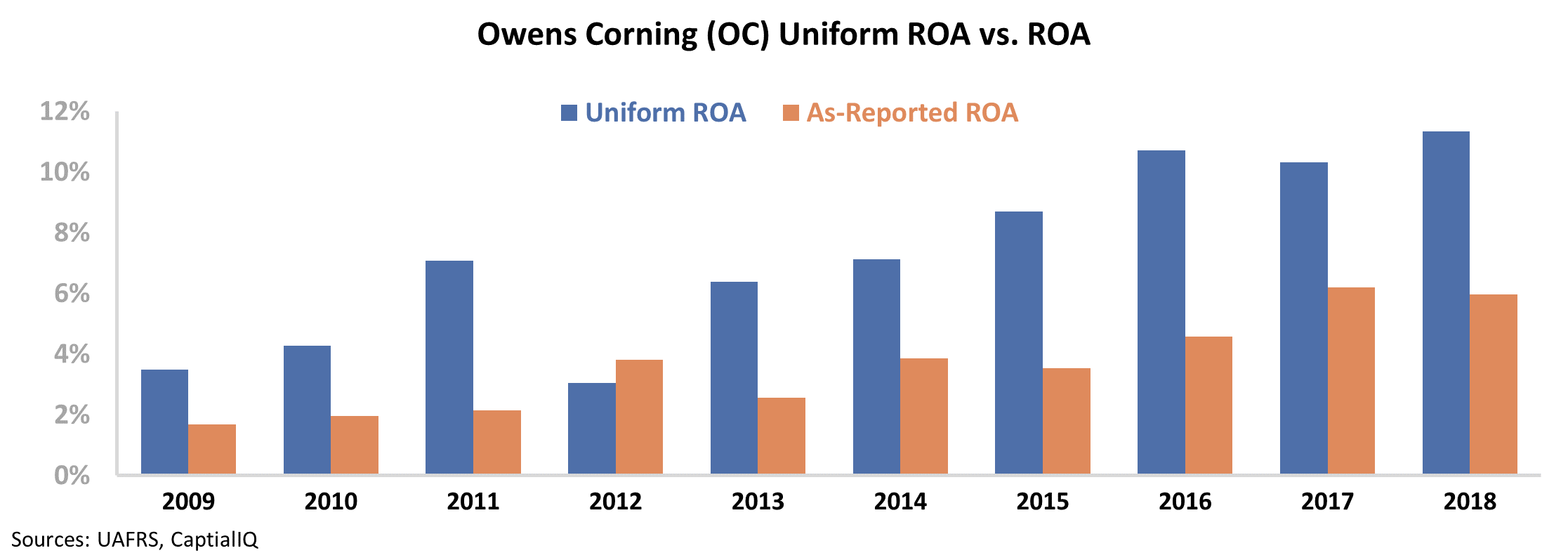

However, once we make the proper adjustments to as-reported financials, we can see that Owens Corning has been able to significantly improve its business since emerging from bankruptcy...

With Uniform Accounting, we adjust for misleading accounting practices like the mistreatment of goodwill, non-cash stock option expense, and operating leases. After making these adjustments, we can see that Owens Corning's ROA has actually come back much stronger, improving to a peak of 11% in 2018. Take a look...

At these levels, the company's recent stock performance may be too conservative compared with its recent performance improvements.

Without looking at Uniform metrics, investors may fail to look past Owens Corning's prior bankruptcy. But once we work through the accounting noise, we can see the real operational trends... and how this company has put its prior issues behind it.

Regards,

Joel Litman

February 21, 2020

The NBA is embracing disruption... and that's not a surprise.

The NBA is embracing disruption... and that's not a surprise.