The Wall Street darlings have been kicked to the curb...

The Wall Street darlings have been kicked to the curb...

For ultra-wealthy investors, the hedge fund has historically been the crown jewel of their investment portfolios. Originally conceived to operate outside of the traditional mutual-fund framework, hedge funds can make wildly speculative trades on any manner of financial instruments – thus driving returns decoupled to the wider market. By doing so, these wealthy investors hope to hedge market risk while generating a sizable return.

However, as Bloomberg reported late last month, hedge funds are under historic levels of pressure... They're suffering from declining returns, increased competition, and high fees.

The fee structure isn't new. Back in the 1990s, celebrity hedge-fund managers such as George Soros and Seth Klarman rose to fame and helped popularize the "two and 20" pricing model. This charges investors both a 2% yearly management fee and a 20% performance fee for the profits made above a benchmark.

After the 2008 financial crisis, returns slumped for the industry. By staying more "market neutral," hedge-fund managers underperformed as stocks entered their longest bull run in history.

This year, hedge funds have been a mixed bag to invest in. Managers such as Boaz Weinstein have benefitted from the current market volatility. However, others like Ray Dalio and Michael Hintze have reported their worst months on record in 2020.

So far this year, hedge funds have lost more than $55 billion in assets as clients have pulled out for greener pastures. This means fund managers are doing everything in their power to draw in customers.

According to Bloomberg, one manager in London has waved performance fees until returns reach a certain level. Another says that he'll only charge the 20% performance fee if the fund earns triple-digit returns. Most radically, a fund in Hong Kong has offered to cover all losses which might be incurred.

These measures are only the first step for an industry which has been resting on its laurels for too long. As such, the fee structure that used to make hedge funds such a compelling business model – which investors used to ignore in the hopes of big gains – is likely on its way out.

We're continuing our coverage of reader requests...

We're continuing our coverage of reader requests...

Today, we'll cover a company that Altimetry Daily Authority reader Paul requested.

In the October 25 Daily Authority, we discussed the concept of the "mill on a hill." A perfect example of this phenomenon is ExxonMobil (XOM). When it comes to mining and oil and gas companies like Exxon, value comes from assets in the ground. The value of these assets usually greatly exceeds the value of the firm's current production.

This is the opposite of most businesses. Usually, a company uses its assets as a means to produce whatever it sells – such as a factory that makes cars, or an office for a sales staff.

For miners and oil and gas companies, the actual assets are by definition the things the firms are selling. This creates an odd situation where the asset base shrinks as the business produces revenue. As such, the company needs to replenish its assets constantly so it can maintain its asset base.

This also means the assets in the ground always have value. This is the case even if the company isn't currently making money or ever planning on mining or drilling. Due to this, the value of these firms can change drastically if its underlying commodity changes in price. Even if the company isn't changing its operation, its value can be volatile.

Seabridge Gold (SEA.TO) is a great example of this. Seabridge never actually produces any gold, copper, silver, or molybdenum. The company's business model isn't even to mine... Seabridge only identifies reserves, sits on them, and then waits. From there, the company hopes it can either find a joint venture partner or someone to buy the assets.

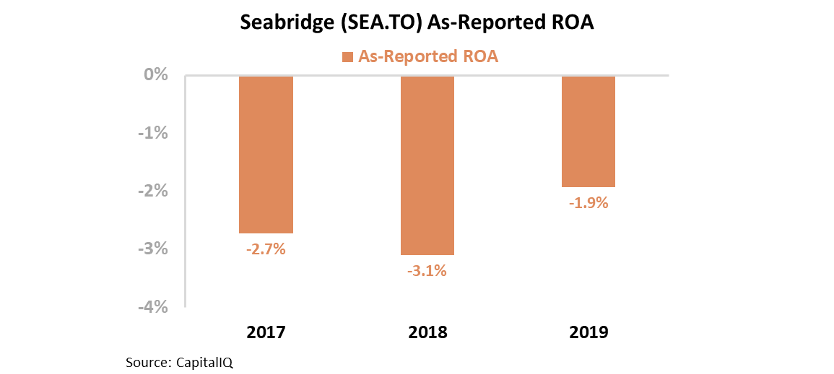

Today, Seabridge has the fifth-highest gold reserves amongst large companies... But as-reported metrics show that Seabridge has a negative return on assets ("ROA"). While at first this may seem unintuitive, it makes sense. Seabridge doesn't produce any revenue, yet still incurs some costs.

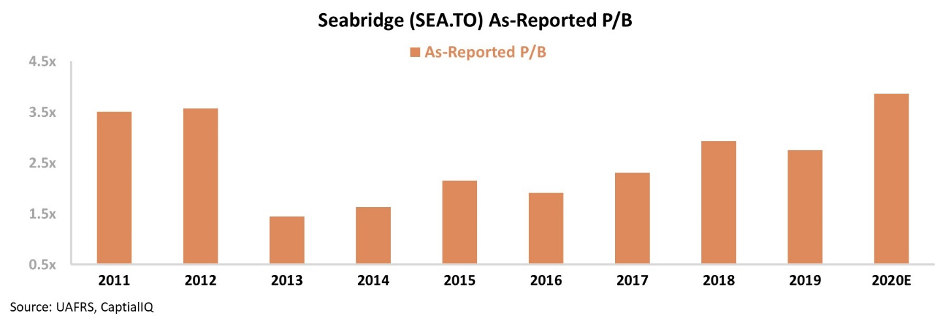

Because its ROA is so negligible, the proper way to look at Seabridge may be through asset-based valuations instead of earnings multiples. Mining companies generally don't trade at a high price-to-book (P/B) ratio, since it's rare the firms can generate returns well in excess of their cost of capital.

Seabridge's as-reported P/B ratio has been on the rise in recent years, but management's positive sentiment may justify this. Not only does the company claim its fifth-highest position in gold reserves, it also claims to be first in gold reserves per share... as well having the lowest enterprise value per ounce of gold.

Take a look below at Seabridge's P/B ratio over the past decade...

Even though the company's as-reported P/B ratio stands at 10-year highs, it's actually even greater than that...

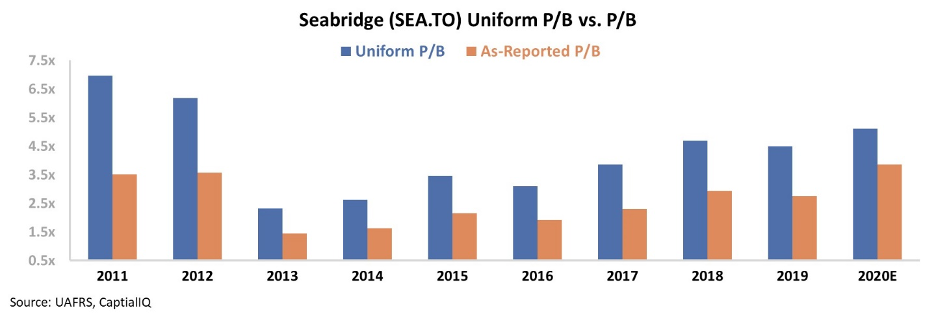

As-reported metrics are distorting Seabridge's valuations. When we remove the accounting "noise" and look at the real Uniform numbers, we can see Seabridge's P/B ratio has been understated every year over the past decade.

This means the company's stock may not actually be as cheap as management makes it out to be. Specifically, Seabridge's Uniform P/B ratio is currently 5.1 times, not 4 times...

A high valuation relative to book value is often unsustainable for any mining company. If the firm is unwilling to extract any gold without a partner, that even further defers any payout – thus adding incremental risk for valuations this high.

This makes Seabridge much riskier than it seems at first glance. This may also mean those rosy metrics management is presenting that put the company in a favorable light may not be the real picture.

Cherry-picked metrics and as-reported accounting have been able to make Seabridge look much more attractive than it actually is. By utilizing Uniform accounting, we can see that there's more risk to this company than meets the eye.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

August 12, 2020

The Wall Street darlings have been kicked to the curb...

The Wall Street darlings have been kicked to the curb...