Activists have been severely hampered in the current environment...

Activists have been severely hampered in the current environment...

Last week, The Economist published a thoughtful article about the effect of the coronavirus pandemic on activist investors. The crisis has significantly damaged their strategies...

- Activists are hard-pressed to insist companies merge when other investors might prefer prioritizing raising debt for operations instead of mergers and acquisitions (M&A)

- The optics of telling a company with no revenue to pay all its capital out to shareholders in a dividend aren't great

- Activists sound tone-deaf if they try to run a proxy battle against a management team when the team should be focusing on making sure that the company in question doesn't have real operational issues in the current environment

Those issues are to be expected, as they crop up in most big sell-offs. But the concern this time around is many companies adopting "anti-coronavirus poison pills."

In the name of defending the business against opportunistic investors and potential acquirers after the major sell-off, companies are adopting more restrictive rules around shareholder ownership levels, strategies to dilute surprise controlling shareholders, and other protections for management and the board.

Protecting corporations from getting bought up on the cheap due to shorter-term disruptions is a worthy cause, and current equity investors should applaud it.

But if this becomes a long-term reversal of the work that activists and other investors have done to improve corporate governance over the past few decades, that would be a serious negative for holding management teams accountable... and therefore a negative for shareholder value as well.

We've been led to believe monopolies are outlawed...

We've been led to believe monopolies are outlawed...

All the messaging we receive from economics, policymakers, and the history books make it seem like monopolies are a concept from a prior era.

President Theodore Roosevelt famously enforced anti-monopoly and antitrust laws during his tenure in office.

He helped break up the Northern Securities Company, which was a trust comprised of three of the largest railroads in the country. Around the same time, tycoon John D. Rockefeller was forced to break up his Standard Oil empire, which was split into 34 distinct companies in order to restore competition to the industry.

While Roosevelt was active at breaking up monopolies, they've continued to pop up throughout history, albeit in different and new forms...

For example, the utility companies that run power grids are granted a form of "regulated monopoly." These businesses wouldn't be able to provide consistent service with competition, so instead the government allows each to own a geographic monopoly with a "cap" on their earnings. This way, they can operate efficiently without gouging customers for an essential good.

Additionally, many people have argued that social media firms are a new form of monopoly. Take Facebook (FB), for instance...

The company owns the two networking apps with the highest daily active users ("DAU") in the globe (Facebook and Instagram) and two of the most popular messaging apps (WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger). On top of that, Facebook continues acquiring smaller tech firms before seeing them grow to be industry giants.

The same argument can be made for Alphabet (GOOGL), which changed its name from Google to reflect the fact that it was now a much larger portfolio of companies than just Google.

If that's not reminiscent of Standard Oil's 34-company trust, I'm not sure what is.

Even the health care industry has introduced some leniency around monopolies...

In order to incentivize firms to create new drugs, these businesses are granted product patents that are like temporary monopolies. In that time, typically more than seven years, the drug makers try to establish themselves to prevent others from developing generic versions.

A great example of this is pharmaceutical company Mylan (MYL), the creator of the EpiPen autoinjector.

A few years ago, the company faced public outrage when the price for a two-pack of EpiPens rose more than 400% to $600.

Unfortunately for those who need them, its nearest competitors all disappeared for various reasons, including research delays and recalls. This cleared the way for Mylan to charge whatever it wanted until the backlash grew large enough.

As an investor, you would expect companies with an effective monopoly to see strong returns. However, that doesn't appear to be the case for Mylan...

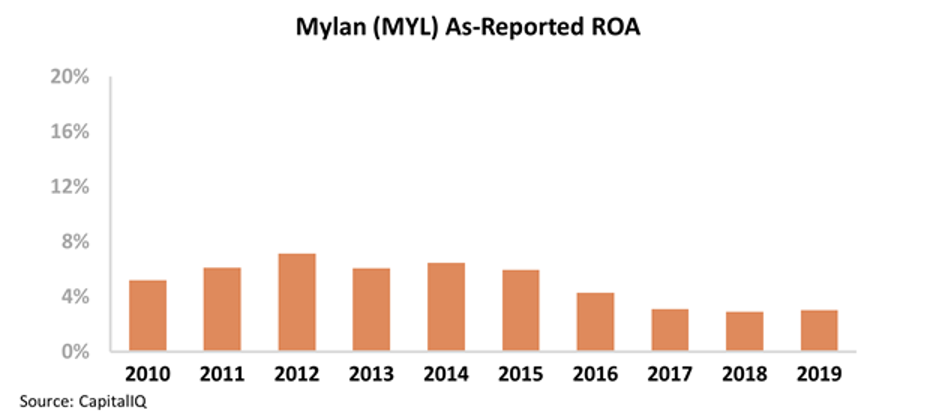

The company has only managed average return on assets ("ROA") for the last decade, and returns have even fallen as it raised prices on EpiPen.

Perhaps the public is overreacting by calling companies like Mylan monopolies...

Or perhaps the as-reported numbers are wrong.

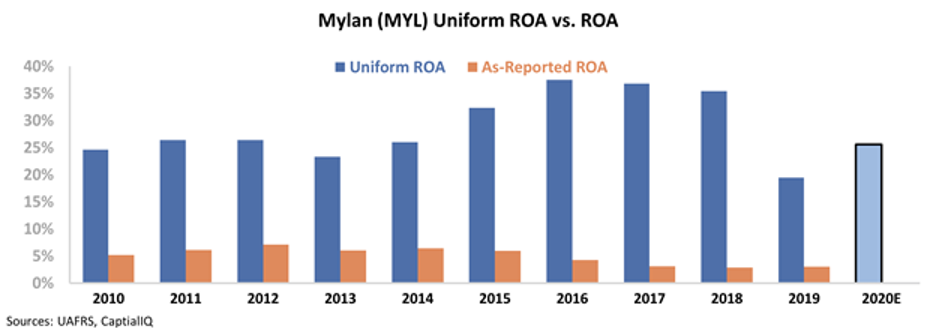

When we apply our Uniform Accounting metrics, we can see a wildly different story. As-reported accounting statements punish companies like Mylan based on the way they treat items like acquisition-related goodwill and research and development (R&D) – two important parts of the company's business.

Once we adjust for these misleading practices, we can see that Mylan's returns look more like a typical monopoly.

The company's Uniform ROA is well above corporate averages, even after taking a hit in 2019. Analyst estimates (light blue bar) for 2020 project Mylan's ROA to start to bounce back as soon as this year. Take a look...

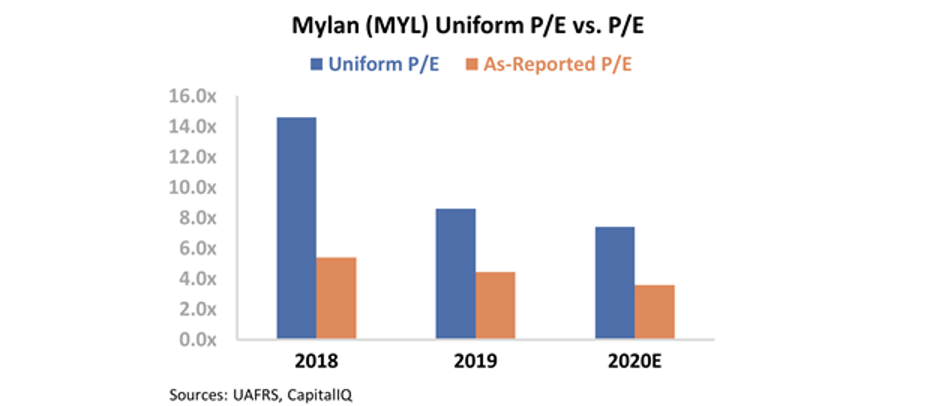

Furthermore, investors seem overly bearish about the company. While Mylan's as-reported price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 4 is slightly lower than its Uniform P/E ratio of 8, both are well below market averages near 20 times.

In fact, it's rare that a company would ever trade at a P/E ratio of 4... This a further indication that the as-reported metrics are likely distorted.

At these levels, Mylan doesn't need to be a monopoly to see serious equity upside in the future.

Regards,

Joel Litman

April 22, 2020

Activists have been severely hampered in the current environment...

Activists have been severely hampered in the current environment...