The 'At-Home Revolution' has meant more toys... and not just for kids.

The 'At-Home Revolution' has meant more toys... and not just for kids.

In early June, I wrote in Forbes that reduced travel due to the coronavirus pandemic has had trickledown effects. One big beneficiary has been golf and golf equipment.

Wealthy people who would normally be vacationing in Europe, the Caribbean, or elsewhere are trapped closer to home. They've been looking for local ways to entertain themselves while still social distancing. Golf is a great way to do that... and with a wealthier clientele – who are somewhat more immune to the negative economic effects of the pandemic – the sport hasn't experienced some of the issues that other industries have.

Golf equipment isn't the only "toy" for adults that has seen surging demand in the midst of the pandemic. Another industry that has seen robust customer interest is pleasure boats.

In the midst of the pandemic, boats have become hard to find. People want to get out on the water in their local lake or ocean, to socially distance and still have fun.

But the interesting effect of people investing more in these "toys" during these times? Even after the pandemic recedes, a lot of folks are going to spend more time near their homes – to make sure they use these sometimes-expensive pieces of equipment they've bought.

It's more evidence the pandemic has helped accelerate and strengthen the "At-Home Revolution"... and that trend is unlikely to change.

Back in the 1990s, General Electric (GE) was wrapping up its decades of expansion under its legendary CEO...

Back in the 1990s, General Electric (GE) was wrapping up its decades of expansion under its legendary CEO...

As we discussed in the October 18 Altimetry Daily Authority, longtime head Jack Welch – better known as "Neutron Jack" – was engaging in a mergers and acquisitions spree to breathe new life into the aging conglomerate.

GE found its humble beginnings in creating light bulbs and electric motors under Thomas Edison's business interests. This manufacturing beginning is the reason why many people think of GE as a manufacturing firm.

However, after Welch was done with his business transformation, GE had become a true conglomerate.

As part of the acquisition spree in the '80s, GE expanded beyond manufacturing to create a financing arm involved in insurance and consumer finance. By 2006, the GE Capital division accounted for 40% of the entire conglomerate's revenues.

Welch's acquisitions completely diversified the company's products. His largest acquisition was RCA in 1985, which put media network NBC back under GE's control after the company's original divestment in 1930.

By 2006, more than 10% of GE's revenue came from its broadcasting business with NBC.

The massive expansion beyond manufacturing has often led to investors misunderstanding how to value the conglomerate.

The issue doesn't end with GE, either. Once investors lock in an idea of a company, that's how they'll categorize that firm... no matter how much it changes. We can see another example of this today with PepsiCo (PEP).

Pepsi – or "Brad's Drink," as it was originally called – first debuted in 1898 as one of many fountain sodas competing for market dominance. After World War II, Coca-Cola (KO) and Pepsi began their long rivalry that has lasted until this day.

However, as we mentioned in the June 1 Daily Authority, Pepsi has grown far beyond its roots as a beverage maker...

In 1965, the company merged with Frito-Lay. In 1998, Pepsi bought Tropicana to expand its drink catalogue into juices... and it merged with Quaker Oats in 2001.

But despite the move into other businesses, many investors still often view Pepsi as a beverage company first and foremost. This is despite the fact that Frito-Lay's North American business alone contributes roughly 50% of Pepsi's operating profits... and that's before factoring in Frito-Lay's international business or Quaker Oats' contribution to revenues.

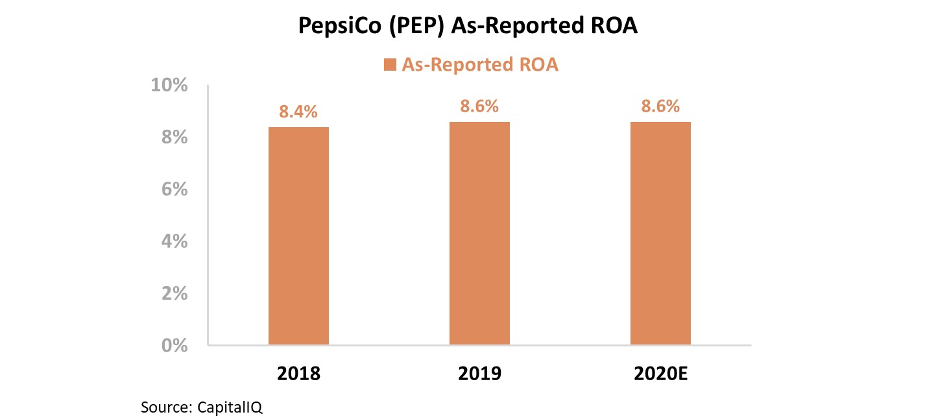

This misconception shows up in the financials. Looking at Pepsi's as-reported return on assets ("ROA"), the company appears to be a typical beverage firm – with consistent returns greater than of cost-of-capital levels.

And yet, the narrative told by these numbers is built on the garbage-in, garbage-out methodology of as-reported accounting.

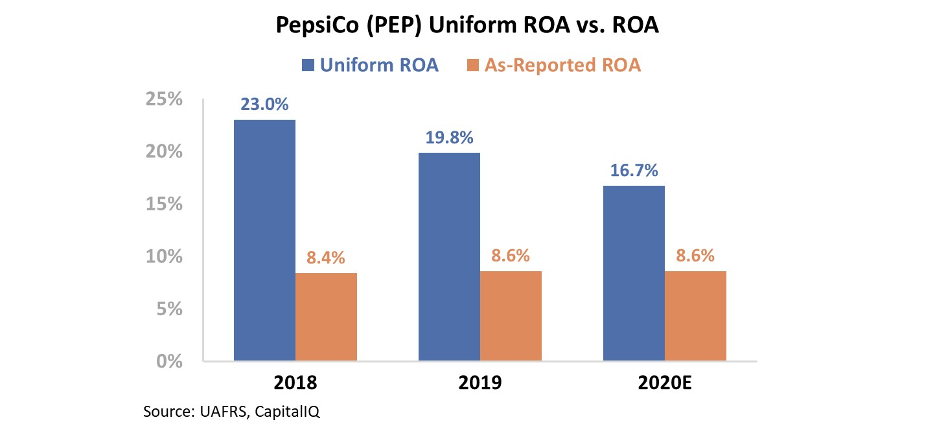

In reality, Pepsi doesn't have the stable returns of a pure beverage company... Much of its revenue now comes from the snack market.

Over the past few years, the snack industry has been under pressure from consumer trends towards healthier foods and away from snacking.

This means that Pepsi's Uniform ROA has been under consistent pressure year after year – with a decline from 23% in 2018 to a forecasted 16% in 2020.

Pepsi's Uniform ROA shows a completely different picture for the future health of the company. Furthermore, by looking at the Uniform price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, we can see how the market still has the wool over its eyes...

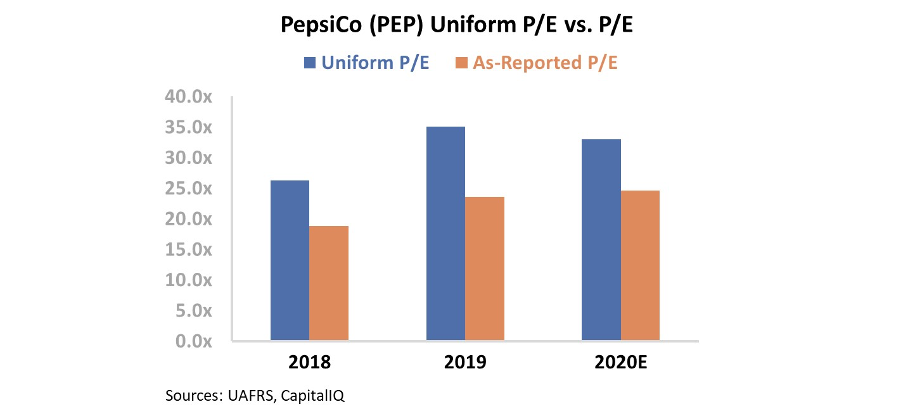

As you can see, Pepsi is currently valued at a Uniform P/E ratio of 32.1 – well above market averages. The market is currently paying a premium for what investors believe is a safe, stable beverage company in the midst of a global pandemic.

However, this excessively high valuation doesn't line up with what Pepsi has become – a snack business in a struggling market.

Similar to GE, Pepsi's origins as a beverage company and the distorting nature of GAAP accounting have led the market astray.

By only looking at the as-reported numbers, it would appear that Pepsi is a strong conglomerate that's in line with direct competitor Coke. But in reality, investors are overpaying for a company that they've misunderstood.

Regards,

Joel Litman

July 14, 2020

The 'At-Home Revolution' has meant more toys... and not just for kids.

The 'At-Home Revolution' has meant more toys... and not just for kids.